Women pose with flowers outside of a "French room" house in Anjar, April 19, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

ANJAR, Lebanon — It’s Sunday evening and about a thousand people have gathered for a procession in the small Bekaa town of Anjar.

Many of them are children and church scouts, carrying torches and marching from one site to the next, led by the local scout band.

They’re here to mark 108 years since the 1915 Armenian genocide, which saw Turkish forces kill more than a million people as World War I raged and the Ottoman Empire crumbled.

“This is a small Armenia,” says Hagop Aintaplian, a 60-year-old vegetable farmer.

On an afternoon a couple days before the ceremony, Hagop tends to his farm by a clear stream outside the town center. He’s proudest of his artichokes, fields of which adorn both sides of a dirt road.

Hagop inherited the farm from his father, who was a little boy when he came to Anjar from what is now southern Turkey’s Hatay province.

But 40 years into his career as a farmer, Hagop says he’s worried about what would happen if his three daughters were to stay here amid Lebanon’s widening economic crisis and political uncertainty. He hopes they will go to Armenia instead.

Hagop sits down to talk in a plastic chair by the stream, still wearing his rubber field boots. He shifts between Armenian and Arabic. For now, he says, Anjar is still home.

“Because I live in Anjar and I have an attachment to the land, it lets me live and stay in Lebanon.”

Hagop Aintaplian in his artichoke field, April 19, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Hagop Aintaplian in his artichoke field, April 19, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Lebanon’s last official census was in 1932, but Minority Rights Group International, an advocacy organization, estimates Armenians to be 4 percent of the population, many of them living in the densely populated Burj Hammoud suburb of Beirut.

Thousands of them came shortly after the genocide, which the Turkish government has yet to formally recognize more than a century on. Most survivors who sought refuge in Lebanon settled near the capital city to rebuild their lives.

Anjar is different.

About an hour and a half from Beirut, past mountains and sprawling farmland, Anjar is best known for its colonnaded Umayyad ruins.

Today’s residents first arrived as refugees in 1939, resettled by French mandate soldiers from what had been the Syrian sanjak (province) of Alexandretta (today’s Hatay). Their ancestral villages were located in what Armenians fondly call “Musa Dagh,” or the Moses Mountain.

That year, French forces in charge of Syria handed over the sanjak to Turkey, according to Joshua Donovan, a postdoctoral fellow at the German Historical Institute Washington’s Pacific Office who focuses on minorities in the Middle East. Musa Dagh’s Armenians feared they wouldn’t be safe if they stayed.

It had only been 24 years since Musa Dagh’s villagers waged an armed resistance in 1915 to survive the genocide that saw Turkish forces kill anywhere from 600,000 to more than a million Armenians, many of them on punishing death marches deep into Syria’s eastern desert.

Manug Keledjian, born in 1887, was from the Musa Dagh region and took part in the 1915 armed resistance against the genocide. He later came to Anjar in 1939. Keledjian’s granddaughter is now married to businessman Yessayi Havatian. To the left are the binoculars Keledjian wore in the photo. Photo taken April 19, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Manug Keledjian, born in 1887, was from the Musa Dagh region and took part in the 1915 armed resistance against the genocide. He later came to Anjar in 1939. Keledjian’s granddaughter is now married to businessman Yessayi Havatian. To the left are the binoculars Keledjian wore in the photo. Photo taken April 19, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The Musa Dagh villagers lost 18 people in that war. Their memory is preserved and revered in Anjar. The other villagers were rescued from that fate via French ships in 1915 and taken to Port Said, in Egypt, for safety. They returned to their destroyed homes in 1918, in what was then French-controlled territory, to rebuild.

But in 1939, as Alexandretta went to the Turks, Musa Dagh’s 5,000 Armenians were evacuated once again, this time across the new borderline back into French mandate Syria. They went onward by foot, ship, train and, eventually, French military trucks.

Their destination, according to the memories they would later pass down: an insect-infested patch of mud in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley.

‘I remember our orange grove’

Anjar's Sirouhie Dukenjian-Shannakian, 92, in her kitchen, April 19, 2023. She came to Anjar as a little girl in 1939. She married at age 29. She has never been able to revisit Musa Dagh, as the trip is too expensive. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Anjar's Sirouhie Dukenjian-Shannakian, 92, in her kitchen, April 19, 2023. She came to Anjar as a little girl in 1939. She married at age 29. She has never been able to revisit Musa Dagh, as the trip is too expensive. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Eighty-four years later, Anjar is a green pastoral town watched over by snow-capped mountains. There are Armenian schools, Armenian storefronts and a huge bowling alley-plus-restaurant that draws in wedding parties and people from nearby towns.

“Because it’s a pretty homogenous village … it’s a bit different from communities where Armenians chose to settle in Aleppo or Beirut,” says Donovan.

Residents still speak the heavy Musa Dagh dialect, though today it’s laced with Arabic, too.

On one quiet street, Sirouhie Dukenjian-Shannakian lives with her daughter Gariné in a modest concrete home adorned with Armenian prayers and avocado plants in potted rows. She is 92 years old.

Sirouhie still remembers threads of her girlhood in Musa Dagh — the inside of her family’s concrete house, the garden, the fruit trees.

“I remember our orange grove,” she says, speaking from a worn red sofa in her kitchen. “Above it was a spring.”

She says her father spent five years building their home in Musa Dagh after returning there with the other villagers from Port Said. But he wouldn’t stay home for long.

“They built that house in Musa Dagh over the course of five years,” Sirouhie says. “And, in the end, they couldn’t even sleep in it.”

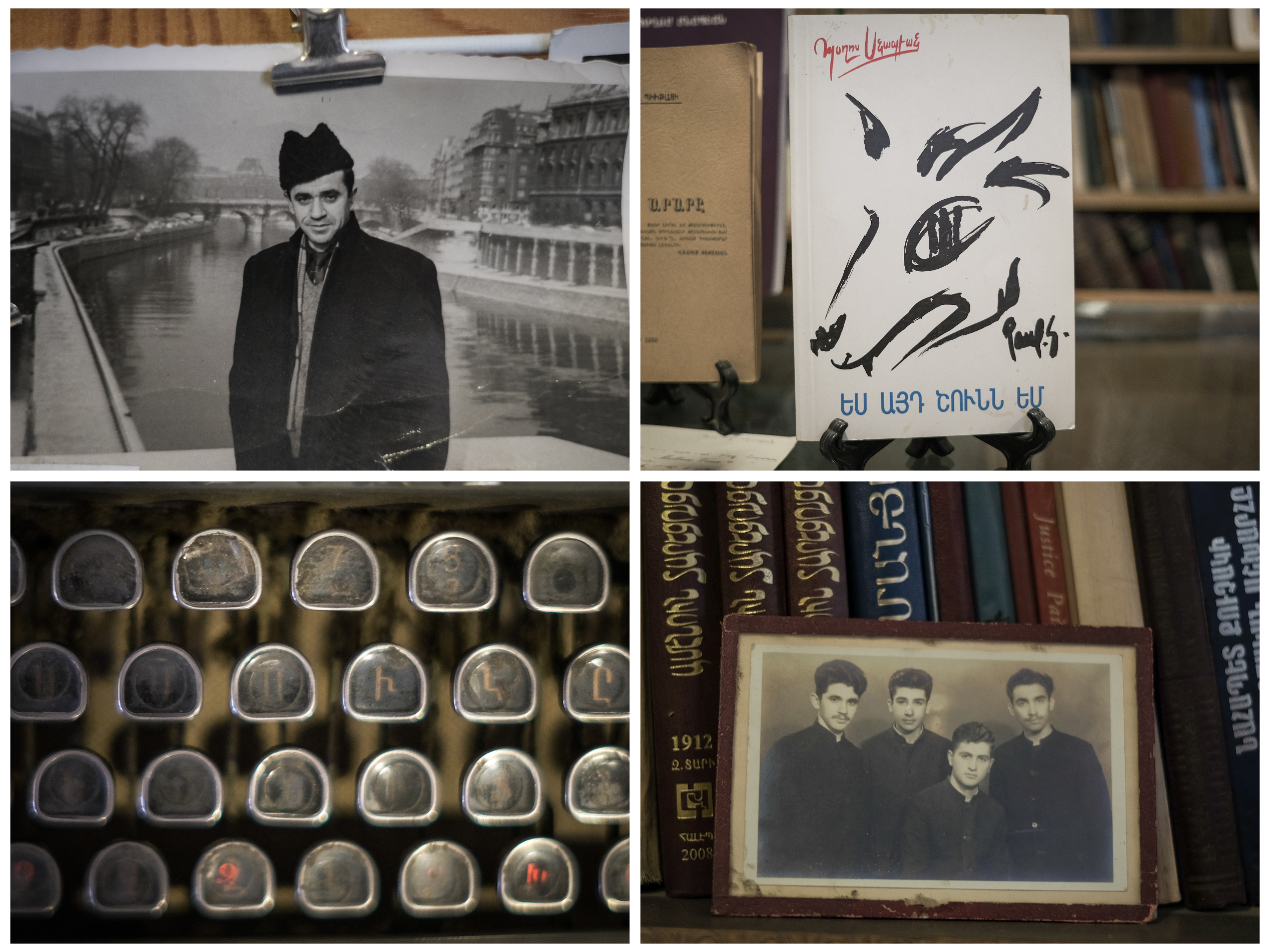

Memorabilia inside Anjar’s Boghos Snabian House Museum, where the eponymous writer once lived and worked, April 19, 2023. Among his works is a 1992 collection of short stories titled ‘I Am That Dog.’ In one story, a dog owned by Armenians in Paris recognizes passing strangers as fellow Armenians. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Memorabilia inside Anjar’s Boghos Snabian House Museum, where the eponymous writer once lived and worked, April 19, 2023. Among his works is a 1992 collection of short stories titled ‘I Am That Dog.’ In one story, a dog owned by Armenians in Paris recognizes passing strangers as fellow Armenians. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

In 1937, two years before the evacuation of Musa Dagh, her father was hired for a construction job in Lebanon. The family left for Beirut and then Tripoli. She was six years old.

Sirouhie’s memories of the time are hazy, she says, “like a dream.” She had little understanding of what was happening around her — why, two years later, they were joining other Musa Dagh families aboard a train from Tripoli to the military station in Riyaq. From there, she says, they traveled via French army vehicles to their new home in Anjar.

There they were greeted with tents and little else.

“There was no school. We were barefoot.”

Sirouhie Dukenjian-Shannakian, 92, holds a picture of herself and her husband, who married in Anjar after leaving Musa Dagh as small children, April 19, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Sirouhie Dukenjian-Shannakian, 92, holds a picture of herself and her husband, who married in Anjar after leaving Musa Dagh as small children, April 19, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The next few years were hard. She remembers hundreds of people dying of insect-borne diseases. According to Hilda Doumanian, the director of the ethnographical museum in Anjar, 1,100 people died from malaria and typhus in the first two years of their resettlement. Ironically, she notes, Anjar means “flowing water.”

Sirouhie’s family, like the others, used French-supplied construction materials to build crude one-room homes to replace their tents. Each one housed multiple families.

Thousands of these boxy concrete “French rooms,” as they are known now, still exist across town, explains Yessayi Havatian, a local businessman who writes about Anjar’s history. He also contributes to the Tashnag-run daily Aztag.

Many of them are hard to spot now, as they’ve become permanent, expanding into full-scale houses. Gariné’s bedroom used to be a French room.

The rest of the house she shares with her mother was simply built around it, as the decades passed.

The two women have never been back to Musa Dagh.

Sirouhie Dukenjian-Shannakian, 92, April 19, 2023. She came to Anjar in 1939 as a young girl. She says her parents ‘didn’t cry’ when they began to realize they’d never return to their home village in Musa Dagh, Armenia. ‘They used to dance,’ instead. ‘They expressed themselves with dance.’ (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Sirouhie Dukenjian-Shannakian, 92, April 19, 2023. She came to Anjar in 1939 as a young girl. She says her parents ‘didn’t cry’ when they began to realize they’d never return to their home village in Musa Dagh, Armenia. ‘They used to dance,’ instead. ‘They expressed themselves with dance.’ (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Artist Koko Garabet in his studio in Anjar, April 19, 2023. The studio is among the town’s ‘French rooms,’ later expanded into a full-size house. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Artist Koko Garabet in his studio in Anjar, April 19, 2023. The studio is among the town’s ‘French rooms,’ later expanded into a full-size house. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

‘Like washing our hands’

About 2,500 Armenians live “permanently” in Anjar today, according to mayor Vartkes Khoshian. That number doubles in the summer, when those living in Beirut or abroad in the diaspora come to visit. He calls the latter the “diasporian” Anjaris.

Lebanon’s economic downturn hit the town hard, Khosian says. Since 2019, that crisis has seen the value of the lira plummet, dissolving the life savings of thousands of people across the country.

“All of the problems found in Lebanon are of course found here,” he says: medicine shortages, unaffordable fuel, decimated salaries. Aid sent from fellow Musa Dagh Armenians abroad has helped lighten the load somewhat, but business is still in the lurch.

“I had a great loss. I lost all the work I did the past 30 years,” says Yessayi, the writer, at his farming supplies business down the road.

Businessman and chronicler of local history Yessayi Havatian outside his farming supplies store on the outskirts of Anjar, April 19, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Businessman and chronicler of local history Yessayi Havatian outside his farming supplies store on the outskirts of Anjar, April 19, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Signs in Armenian, Arabic and English adorn Anjar’s streets, April 19, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Signs in Armenian, Arabic and English adorn Anjar’s streets, April 19, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Downstairs at the cash register, workers line up to buy seeds and fertilizer from Yessayi’s 32-year-old daughter Nare.

The economic crisis has meant Yessayi’s seasonal credit-based business model crashed hard. He now only takes cash payments.

“It was like washing our hands,” Havatian says of losing his money in the crisis.

Other residents have also switched professions to stay afloat, turning from goldsmithing – a profession Anjar was once famous for – to farming, despite the financial risks, explains Khoshian.

Yessayi is keeping the business running and says he feels optimistic about remaining in Lebanon. Since the early 2000s, he’s also visited Musa Dagh several times with his family.

“I am Lebanese, more than 100 percent, because I live here and will die here,” Yessayi maintains.

“But this doesn’t mean that I don’t visit Armenia, that I don’t have a house there. This doesn’t mean I’ve forgotten.”

Hagop, too, is forging ahead with agriculture.

For him, though, the future is torn between Anjar and Armenia.

For the past few months he’s been experimenting with growing his prized Anjar artichoke roots on friends’ lands in Armenia. He hopes they’ll grow well in the soil there, so that, if he wants, he could start over as a farmer once again and have steady income outside of Lebanon.

By June or July, when the artichokes are supposed to mature, he’ll know if his plan was a success.

Will he make the leap to Armenia if the experiment goes well? Hagop simply laughs. If the artichoke roots hold, he says, “then I’ll plant them.” He’s already bought an apartment in Yerevan, he adds.

Leaving his land in Anjar would still be difficult.

“This is my home, and Armenia is my watan.*”

Anjar's procession to commemorate the Armenian genocide, April 24, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Anjar's procession to commemorate the Armenian genocide, April 24, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Additional reporting contributed by MJ Daoud.

*Arabic for homeland.