Armenian orphans at Palace Nassib Pacha Joumblatt, 1923. (Photo by Nellie Miller-Mann. Courtesy of the Mann Family)

SAIDA — Sitting in the living room of her house, 90-year-old Makrouhi Aslanian faintly recalls hearing that the Americans came and took away the Armenian orphans in Saida.

She was referring to the Birds Nest orphanage, managed by the American charity Near East Relief.

The genocide that started in 1915 killed about 1.5 million Armenians and displaced thousands of others who sought refuge in former possessions of the Ottoman Empire, including Lebanon. Among them were children who had lost their parents, who were housed in orphanages run by Near East Relief.

One of those was in the palace of Nassib Pacha Joumblatt, in Saida.

Some areas of Lebanon, like Burj Hammoud, Antelias and Anjar, are well known for their Armenian population. Saida, though predominantly Sunni, had a thriving Armenian community before the Civil War. At its height in the 20th century, Saida’s Armenian population comprised nearly 80 families, according to the few remaining residents to whom L’Orient Today spoke. They helped mold the face of the city, and contributed to the makeup of the urban fabric that prevails today.

Makrouhi Aslanian, front row left, and her family in 2018. Michael and Alexander are in the second row. (Courtesy Alexander Aslanian)

Makrouhi Aslanian, front row left, and her family in 2018. Michael and Alexander are in the second row. (Courtesy Alexander Aslanian)

According to Danish historian Matthias Bjørnlund, the orphanage was originally in the town of Jbeil. However, the two Danish women running it needed more space, so they looked around and found the palace in Saida. Although derelict, they chose it because of its sprawling grounds and because a well-kept home would have cost more to rent.

The two Danes, Maria Jacobsen and Karen Marie Petersen, used a 5,000 kroner grant to run the place. They moved in 400 refugee orphans in 1923.

The palace was perched on a hill on the outskirts of Saida, and commanded unparalleled views of the city and the sea.

Many of Saida’s locals know the structure as Joumblatt Palace. Surrounded by citrus orchards, it had been built in 1885 by a high-ranking Ottoman official, a relative of Walid Joumblatt, Nassib Joumblatt Basha. After his death, his son could not maintain the house's upkeep, so it fell into disrepair.

One visitor to the orphanage, W. G. Clippinger, President of Otterbein College, recounted in the New Near East that “the nest is a beautiful mansion, abandoned by some previously wealthy person and turned over to Near East Relief to shelter these parentless babies. It overlooks the placid waters of the Mediterranean Sea. In the rear is a large playground in which is a sparkling fountain,” with a temporary structure built to house a school.

It was named The Bird’s Nest because the Danish women felt the Armenian orphans looked like hungry birds, because they were starving. The women repaired the palace, installed electricity, planted a vegetable garden and built a bakery to help feed the children.

Breakfast at the orphanage, 1923. (Photo by Nellie Miller-Mann. Courtesy of the Mann Family)

Breakfast at the orphanage, 1923. (Photo by Nellie Miller-Mann. Courtesy of the Mann Family)

Some of the earliest photographs of the Joumblatt palace were taken by American photographer Nellie Miller-Mann, who was around 26 when she visited the orphanage. She also served as secretary to Near East Relief’s treasurer.

Once a feature of Saida’s little-known Armenian community, the orphanage relocated to Jbeil in 1928, where it persists today. Like other stately homes in Lebanon, the palace is now much changed. The citrus trees that once surrounded it have been replaced by apartment complexes. Its commanding view of Saida is still intact, though, and the palace is now a popular venue for wedding receptions.

Makrouhi Aslanian’s father was a young man when he left Adana with his mother for Tripoli. He then relocated to Syria for 16 years before being offered a job in a glass factory in Saida.

“So we came to Saida,” Aslanian said, “and have been here ever since.”

She recalls that there was a school where children learned Armenian, situated in a small wooden building, built on land rented for one gold lira.

The school itself was built by another Armenian resident of Saida, Simon Zeron Kizirian. His son, 79-year-old Samo Kizirian recalled over coffee in his office how his father came to Lebanon in 1920 at the age of 13, after his parents and siblings were killed during the genocide. He settled in Saida, where he worked for the railroad company which at the time was building a line to Palestine and Egypt.

He was one of the first Armenians in Saida to read Arabic, being self-taught, which helped him become an intermediary between the Armenians who didn’t know Arabic and the government.

Kizirian later became a representative of the Tashnag party in the city. “Anyone who wanted to do work with the Armenians had to pass through him,” said his grandson, Serop.

The school operated on donations from Lebanon’s Armenian community. “He used to get a teacher from Beirut to sign a contract for him to teach and this teacher used to live inside the school,” said Samo Kizirian.

Real estate developer Samo Kizirian in his Saida office, April, 2022. (Photo: Mohamed El Chamaa)

Real estate developer Samo Kizirian in his Saida office, April, 2022. (Photo: Mohamed El Chamaa)

At its peak, in the 1930s and ’40s when Armenians were still new to Lebanon, the school had about 60 students. “It was a free school. He only used to take five lira per head during registration time,” Kizirian recalled. The school taught Armenian and Arabic to children in Saida, up until the 5th grade. Samo Kizirian and his siblings were taught there, as well as other Armenian kids like Makrouhi Aslanian, who later went on to teach there.

After the 1956 Earthquake, the elder Kizirian solicited donations from the Armenian community to rebuild the school, next to which he erected a church. Though initially for Armenian Orthodox, it welcomed all denominations, said Samo.

“We also used to have Armenian Catholics and Protestants,” he said, “because they were all coming and had just survived the Genocide. We didn’t differentiate between religions.”

The school and the church closed before the start of the Civil War, after Simon Zeron Kizirian died in 1962. Today, the site of the Armenian school, a temporary structure on leased land, hosts Saida’s vegetable market, in the souks area.

Makrouhi says Saida’s Armenian population first began to decline in the 1940s when they either moved to Soviet Armenia or to Beirut.

Many of Saida’s Armenian families had been farmers and craftsmen in Anatolia before fleeing to Saida. Today, around five Armenian families remain. Kizirian and Aslanian’s families are among them.

Makrouhi Aslanian’s nephew, Mickael — the child of a Palestinian mother and am Armenian-Lebanese father — says that many Armenians who came to Lebanon were originally relocated to Anjar, Beirut, as well as Saida and Sour. They used to settle where they worked to save on transportation costs.

After 1984, he says, many Armenians started leaving the city for Beirut or to go abroad. Few Armenians returned after the end of the Civil War.

Mickael Aslanian’s brother Alexander disputes claims that Armenians left because of violence during the Civil War. He says that nothing happened to the Armenians in Saida. They didn’t leave because of the war. “They immigrated,” he insists, “just like every other person who immigrated.”

Armenians started moving out to Beirut, he adds, if their livelihood really improved, they would migrate to Europe or to Canada.

“To be honest,” adds Samo Kizirian, “the Civil War really didn’t affect the Armenians Saida, because the people in Saida are very kind. Some people tried to divide us but it didn’t work.”

With its church long since gone, Saida’s Armenian community now has its services at Saint Nishan Armenian Orthodox Church in Downtown Beirut. Unlike the 1920s and ’30s, when nobody spoke Arabic, Alexander says that today few of Saida’s Armenians speak Armenian, his cousins included.

Although few Armenian families remain, their legacy has spread through every corner of the city. Samo’s elder brother, 90-year-old Serop, built several blocks of residential units on the outskirts of Saida for low-income housing, using money he won in the lottery in 1956. Today locals still call the entire area “Serop.” The same is true of the mosque that he helped build in 1962 — raising money from local notables and a Kuwaiti philanthropist, Abdul Latif Othman.

In the 1980s, Saida’s cemetery was full and religious authorities needed a place to bury their dead. Serop sold them a parcel of land at a decent price.

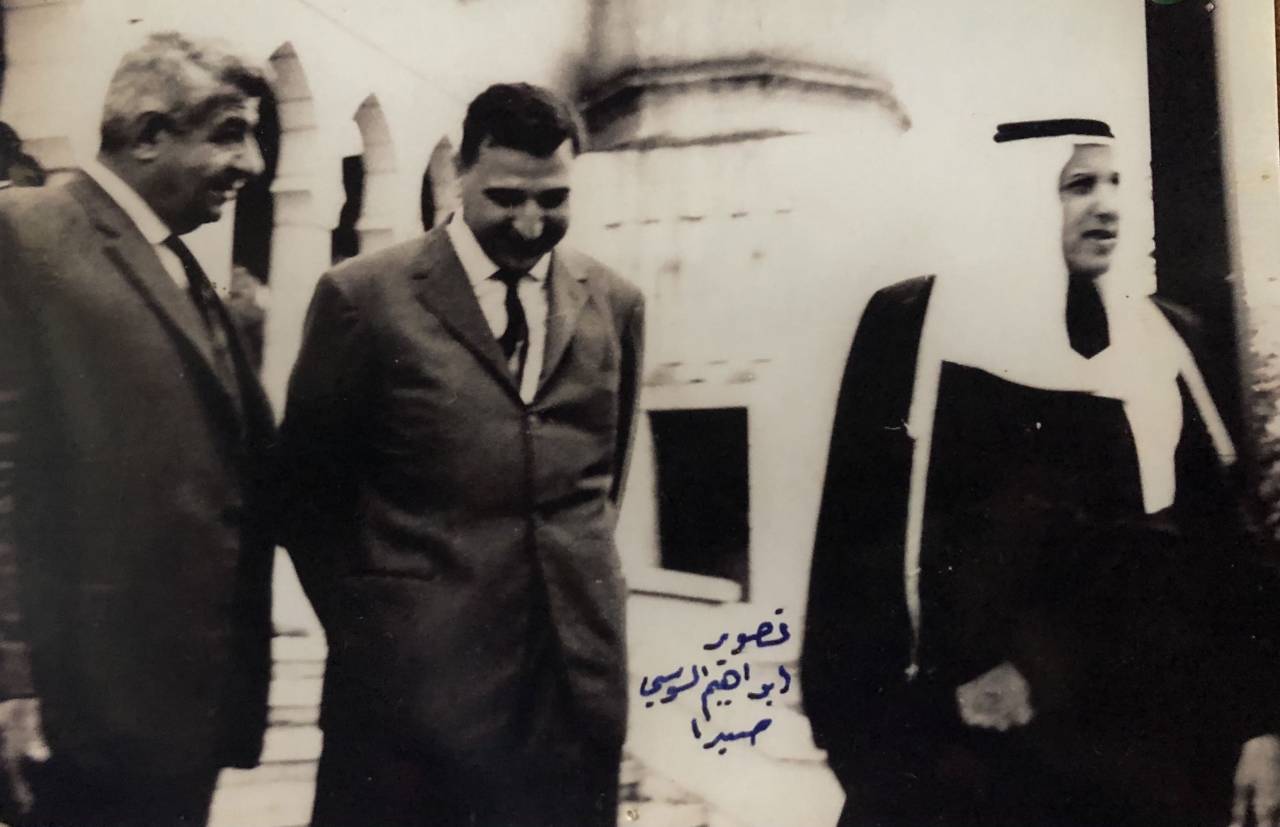

Serop Kizirian, middle, poses before the mosque he helped finance with Kuwaiti philanthropist Abdul Latif Othman, right, in 1962. MP Marouf Saad stands to the left. (Photo: Ibrahim Sossi)

Serop Kizirian, middle, poses before the mosque he helped finance with Kuwaiti philanthropist Abdul Latif Othman, right, in 1962. MP Marouf Saad stands to the left. (Photo: Ibrahim Sossi)