A street in Akkar, Lebanon’s northernmost and often most neglected governorate, which is experiencing a high rate of cholera cases. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

BEIRUT — As Lebanon grapples with its first cholera outbreak since 1993, municipalities say they are bearing most of the financial and medical burden.

This is especially true in the northern governorate of Akkar, where the vast majority of the country’s 400 confirmed cases are located.

“Today municipalities are suffering a double catastrophe,” Ahmed El Mir, the head of the Union of Coastal and Central Municipalities of Qaitea, in Akkar, told L'Orient Today.

Lebanon’s municipalities are overstretched amid an unprecedented economic crisis that has slashed budgets, decimated the value of the Lebanese lira and limited their resources. Municipal authorities are now struggling to tackle the additional pressure of cholera.

Their limited resources stem from the way municipalities are structured. According to Mona Harb, a professor of urban studies and politics at the American University of Beirut, city governments can only earn revenue through a few direct streams, such as issuing building permits and collecting municipal taxes.

There are also “the indirect taxes that the state provides [to local municipalities] with, on telephone [bills], for instance, and other services,” Harb said.

In reality, the latter often go unpaid while the former means “the richest municipalities are the ones that are urban, where you have a lot of real estate activities happening,” according to Harb.

But in Akkar, Lebanon’s northernmost and often most neglected governorate, “you won't have access to such income,” Harb added.

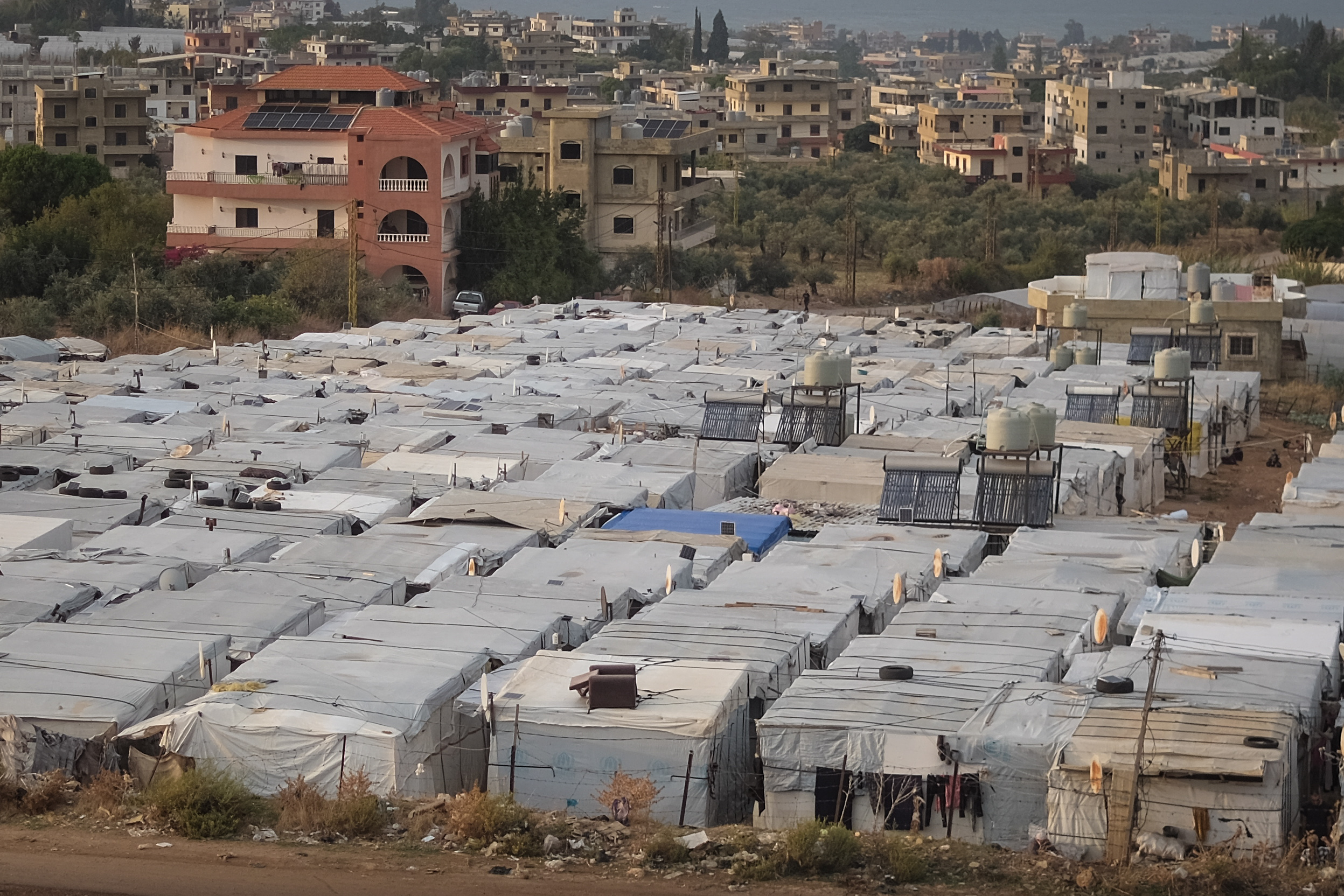

View of Rashiniyeh refugee camp in Akkar, northern Lebanon. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

View of Rashiniyeh refugee camp in Akkar, northern Lebanon. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Indeed, many of the Akkar towns visited by L’Orient Today in recent days to observe the cholera response were low-income and low-density. Buildings are no more than three to four stories tall and there is little ongoing construction, which would generate the kind of income municipalities need to collect from building permits.

Other sources of revenue include transfers from the state through the Independent Municipal Fund, an intergovernmental grant system funded through eleven taxes and fees collected by the Finance Ministry. However, this payment is delivered, on average, every three years instead of annually.

Additionally, overall revenue is barely enough to cover administrative costs, let alone public services and, now, a cholera outbreak.

“On the one hand you have all these diseases and these natural disasters and on the other hand we can’t function properly and we don't get any support from the government,” Mir told L’Orient Today.

He said the money municipalities do receive in the form of taxes is not enough for municipal expenditure, noting that the smallest town in the union receives LL150 million while their garbage removal costs LL800 million annually.

Although the Health Ministry has stepped up efforts to stem the spread of cholera in Akkar, much of the response is being facilitated by local municipalities with the help of international development agencies and, in some cases, grassroots efforts by residents themselves.

This, Harb said, is the “mode of operational governance that has been in place for a while, and that gets reconfigured, I would say, depending on each crisis.”

This standard mode of operation for local governments became the norm after the end of the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israeli forces. More recently, Harb explained, this became the case after the state largely abdicated its role during the Syrian refugee crisis to under-resourced municipalities.

Now, local governments have to carry the burden once more — with whatever outside help they receive.

The UNICEF logo appears on boxes of IV rehydration bags used to treat cholera patients in Akkar, northern Lebanon. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

The UNICEF logo appears on boxes of IV rehydration bags used to treat cholera patients in Akkar, northern Lebanon. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

This was evident in the newly erected cholera field clinic in the basement of the Habib al-Mustafa Mosque in Bebnine: it was established with help from UNICEF, the town’s mayor told L’Orient Today. UNICEF logos were visible on many of the boxes carrying IV rehydration bags for the cholera patients.

Bebnine happens to be the Akkar town with the highest number of cholera cases. Its mayor, Kifah Kassar, told L’Orient Today on Tuesday that “UNICEF, in cooperation with the North Lebanon Water Corporation, took the initiative to operate a well” to provide clean water in the town.

Other grassroots initiatives are also stepping in to fill gaps in potable household water, with some activists distributing water bottles to families.

Harb said this is not uncommon in other places around the world.

“This is the way you operate in the context of limited statehood,” she said. “And we’ve been reaching that stage progressively over the past years.”