Five foreign models at the Petits Lits Blancs Ball in 1964 wearing LL18 million worth of jewelry. (Credit: L’Orient-Le jour archives) Five foreign models at the Petits Lits Blancs Ball in 1964 wearing LL18 million worth of jewelry. (Credit: L’Orient-Le jour archives)

BEIRUT — There are numerous Instagram accounts dedicated to Lebanon’s past, and specifically its so-called “golden age,” in the pre-war years.

Amid all the sepia-toned snapshots of bathing beauties and Ottoman-era mansions, one account stands out due to its thorough research and original archival gems. “Lebanese Fashion History” guides the follower through an intricate maze of everything from vintage magazine covers featuring Lebanese top model Mona Yammine Ross lounging on a swing chair at interior designer Sami al-Khazen's Faraya home, which was featured in Architectural Digest in 1974, to an archival reportage about how the 19th-century boom of sericulture (silk farming) in Mount Lebanon led to a social revolution as women were empowered through wage culture. And bewitchingly behind-the-scenes footage of a young Haifa Wehbe in one of her first TV appearances in Assi Hilani’s video for his 1985 Bedoui-inspired song, Ya Mema.

Who is the self-described “obsessed” couturier-cum-lawyer behind the wildly popular account?

Joe Challita remembers exactly what drove him to leave a successful career as a fashion and costume designer to dedicate “every waking moment” digging up random tidbits and photographs, interviewing legends and everyday Lebanese with a story to tell, and chasing after archives to uncover Lebanon’s sartorial sagas.

His interest in fashion dates back many years. As a kid growing up in a Lebanese-Australian family between Lebanon and Wollongong, he was already sketching designs, inspired by his mother, who always designed her own clothes. She would take her son fabric shopping and bring him along on trips to the tailor, where he watched the fittings in awe.

After obtaining a degree as an attorney, Challita decided to pursue his lifelong dream of becoming a fashion designer.

Ultimately, his dream came true. Not only did he launch his own label in 2009 in Beirut, he also participated in the TV competition "Mission Fashion," which resulted in his invitation to train with the famous Lebanese designer Elie Saab — and his career was launched. He was asked to dress the host of "The Voice-Egypt" and to create outfits for Australian celebrities for red carpet events. He designed the wardrobe of British celebrity Myleene Klass for three years and worked with Lebanese soprano Hiba Tawaji, most notably for her opening concert of the Batroun International Festival in 2014 and hosted a fashion segment on LBC’s "Bi Beirut" program.

While he had built his career in Lebanon, having moved back to his home country in 2011 at the age of 32, after the Beirut port explosion and the unfolding of the economic crisis, he left again, moving his family to the UAE, where he “started looking at Lebanon as an outsider.”

“Although I’ve always been curious about delving into my roots and my heritage, and our fashion history was always in the back of my mind, I never did anything about it when I was living in Lebanon. And I think it’s exactly because of that: I was in Lebanon,” Challita tells L’Orient Today from his “mercifully air-conditioned" apartment in Dubai.

Lebanese top international model of the 70s, Mona Ross, wearing dress by avant-garde Lebanese designer Jacques Cassia in Byblos. (Courtesy of Karen Cassia/Joe Challita Collection)

Lebanese top international model of the 70s, Mona Ross, wearing dress by avant-garde Lebanese designer Jacques Cassia in Byblos. (Courtesy of Karen Cassia/Joe Challita Collection)

Turning guilt into glory

He doesn’t regret his choice to leave Lebanon (“I had to, because of my children,” he says), but the enthusiastic Lebanese Australian soon found himself overwhelmed with guilt.

“I almost felt as if I had betrayed my country by leaving,” Challita says. At the same time, he said, “I was so proud of my fellow compatriots. Everything the youths were doing, helping everyone in need, made me ask myself: ‘What can I do for my country?’”

And although he says he’s aware of “sounding like a cliché” he decided he could contribute by spreading awareness and documenting and archiving the country’s past.

“While tomorrow may not be certain, the past is. We can look back and see what we achieved. And understand ourselves more.”

The lack of proper fashion museums and quality historical costumes of Lebanon prompted Challita to return to his costuming passion.

He shifted his skills as a couturier into creating historical Lebanese outfits for a future exhibition.

“My passion, which has evolved into an obsession, has become a full-time job,” Challita says. That passion was also the spark for his popular Instagram page.

Challita says his main goal is to highlight the depth of Lebanese culture and fashion history and to give the new generation some raw material that shows off everything that Lebanon had to offer during what many consider its peak era.

“My page is not about nostalgia and dwelling on the past. The page is to educate and highlight key figures that played an important part in our history, putting Lebanon on the global map,” he says.

Beyond glitz and glamor: An ode to craftsmanship

“Lebanese Fashion History” is also an ode to craftsmanship and the history of textiles.

For instance, one post shows a series of the stages of wearing the baggy pants known as sherwal from childhood in the ‘20s through adulthood in the ‘50s in the village of Kfarsghab in the Zgharta district of North Lebanon. It’s one of many examples where Challita was allowed to showcase photos from a private collection (in this case, the photos are of Barakat Barakat, whose granddaughter Nicole Barakat provided them to Challita).

Another sees Challita highlighting an embroidery detail on a kubran (velvet coat) worn by a 19th-century woman from Beirut, courtesy of Bonfils Studio in Beirut from the Fouad Debbas Collection.

Many of the stunning photos double as tiny history lessons about Lebanon’s multifaceted history, recent and ancient. A photo of Queen Elizabeth I’s coronation, for which “she turned to her trusted designer Norman Hartnell to create what is arguably the most significant gown of her reign,” is accompanied by a short soliloquy about Phoenician Purple, a shade developed in by the Phoenicians in Sour around the 16th century BC by harvesting sea snails — “a gift from Tyre, Lebanon to the world,” Challita quips — diving into the fact that, during the Elizabethan era, only close relatives of the royal family were allowed to wear purple as it was regarded as the symbol of power, wealth and luxury.

Challita also isn’t afraid of regaling his followers with some constructive criticism when sharing some of his more nostalgic nuggets.

Commenting on a video compilation of what Miss Lebanon contestants wore to showcase “the national costume of Lebanon,” he writes: “Looking at the costumes throughout the years, I feel some are not based on any historical research and there's a lack of accuracy. I really hope that more effort is put into designing a stunning costume with a historical reference and accuracy along with the designer's personal touch.”

So, with this passion project usurping most of his time, a labor of love and obsession, which requires him to travel to Lebanon often to dig through archives and interview people, writing about fashion, does he not miss designing and creating in the belly of the beast, the magnificent muse called Lebanon?

“To be honest, aside from choosing the best option for my children, work in Lebanon during the crisis wasn't going well for anyone,” Challita says with a sigh. “Not because of a lack of interest but people just don't have money to spend on luxuries like couture, which is what I specialize in.”

He didn't want to bring the level of work down by, for instance, working with cheaper fabrics, he said. "You know, I was always proud of using 100 percent natural silks. And I worked very small, but exclusively, preferring the old-fashioned way, you know, creating a piece made by the artist himself rather than by a tailor. It’s a bespoke garment. And I wasn’t willing to compromise on my principles.”

“Coming here [to Dubai] and hitting my forties felt like a new beginning for me,” Challita says. As he grew satisfied with his achievements as a fashion designer he realized it was the perfect time for him to up the game and give back. Creating an archive of Lebanon’s fashion history and spreading global awareness about its sartorial heritage is worth sacrificing his time for.

“And again, as cliché as it sounds, I feel like I'm doing something for my country. And no one will understand this unless you're part of the diaspora,” he says. “Many in Lebanon tell me: why would you care? But I simply can’t do anything but care.”

Lebanese iconic hairdresser Loutfi Berberi, grand prix winner of the prestigious and international hair festival, Gala de L'Elegance, Paris, 1980. Model (left) wearing a abaya by Lebanese designer William Khoury who also won the fashion segment of the festival. Award given to Loutfi by French actress Marina Vlady (standing right). Loutfi had won several international hair awards for Lebanon and he was known for his iconic and chic chignons defining Lebanese 70s and 80s haute coiffure. (Credit: Joe Challita Collection, courtesy of Valerie Berberi)

Lebanese iconic hairdresser Loutfi Berberi, grand prix winner of the prestigious and international hair festival, Gala de L'Elegance, Paris, 1980. Model (left) wearing a abaya by Lebanese designer William Khoury who also won the fashion segment of the festival. Award given to Loutfi by French actress Marina Vlady (standing right). Loutfi had won several international hair awards for Lebanon and he was known for his iconic and chic chignons defining Lebanese 70s and 80s haute coiffure. (Credit: Joe Challita Collection, courtesy of Valerie Berberi)

Bombed out closets

The question Challita gets asked the most is “do you have any dresses from this or that designer?” And he usually has to tell them the same thing: “Either a closet got bombed or they were robbed in the war,” Challita says almost incredulously. “It’s always the same line, even when I met with the [1971] Miss Universe, Georgina Rizk.”

While meeting with Rizk last summer, he asked her the same question that many of his followers ask him: “Do you have any archives? Do you have any dresses or even any photos for future exhibitions?” But she said her closet had gotten bombed and most of her Miss Universe-era dresses and photos were lost to history.

Luckily for his followers, Challita gets a kick out of retrieving that very history.

“For instance, I would hear people say that Brigitte Bardot came to Lebanon. Okay great. Where did she go, what did she do, what did she eat, who did she meet? Where is the footage? Show me!” Since he couldn’t find any of that information, he made it his mission to answer his own questions. To satisfy his own curiosity but also for the sake of posterity.

“I managed to find footage of Brigitte Bardot’s visit to Lebanon [on a French Instagram account celebrating the sunglasses she was sporting] and shared it to my account. People went crazy for it!”

His favorite part of the process is “putting together the puzzle.”

“You never find the complete story of an event or something that happened in one source. So each time I find the source with one little description, and then I find another source, I stumble upon another source, like maybe two months later. That’s how I build the story.”

“It's investigative work,” Challita says, “and it gets addictive.”

But he makes sure to point out that it’s a collaborative, communal effort. “I couldn’t do this without the kindness and enthusiasm of others,” Challita says. “Not to mention the unconditional trust they have in me. There are families who hand over their entire family archive to me so I can scan it, just because they follow my account and believe that what I do is important.”

From fashion designer to fashion historian

Currently, Challita is working on “immortalizing the lost golden years of the who’s who in the fashion scene” through a book and an exhibition that will travel to major capital cities, carrying with it the eternally fashionable Lebanese spirit.

His work caught the eye of the French fashion institute Fonds de Dotation Maison Mode Méditerranée, which gave him a grant to support his work to preserve a part of the Mediterranean heritage.

Challita loves delving into the minutia of fashion history.

He could talk all day about Madame Salha, the first designer to establish a “Maison d'Haute Couture” during the fifties, which led to her working with Balmain and Valentino. Known as the “Christian Dior of the Middle East” Salha ended up dressing royalty like Iran’s Queen Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiary and icons like Sabah and Umm Kulthum.

Raife Salha, Lebanon's first official couturier that put Beirut on the global map. Having dressed royals and celebrities in the 1950s and 1960s, Madame Salha was dubbed as the 'Christian Dior of the Middle East, most notably known for her iconic bridal gown designed for Princess Lamia Solh in 1961, making international headlines for having the longest train in the world. (Credit: photo: Joe Challita Collection, courtesy of Ghada Salha)

Raife Salha, Lebanon's first official couturier that put Beirut on the global map. Having dressed royals and celebrities in the 1950s and 1960s, Madame Salha was dubbed as the 'Christian Dior of the Middle East, most notably known for her iconic bridal gown designed for Princess Lamia Solh in 1961, making international headlines for having the longest train in the world. (Credit: photo: Joe Challita Collection, courtesy of Ghada Salha)

Salha also designed Fairuz’s wedding dress and made headlines for designing the longest wedding train in the world, measuring 22 meters, which she created for the Lebanese Princess Lamia Solh, daughter of former Prime Minister Riad al-Solh, who married into the Moroccan Royal family in 1961.

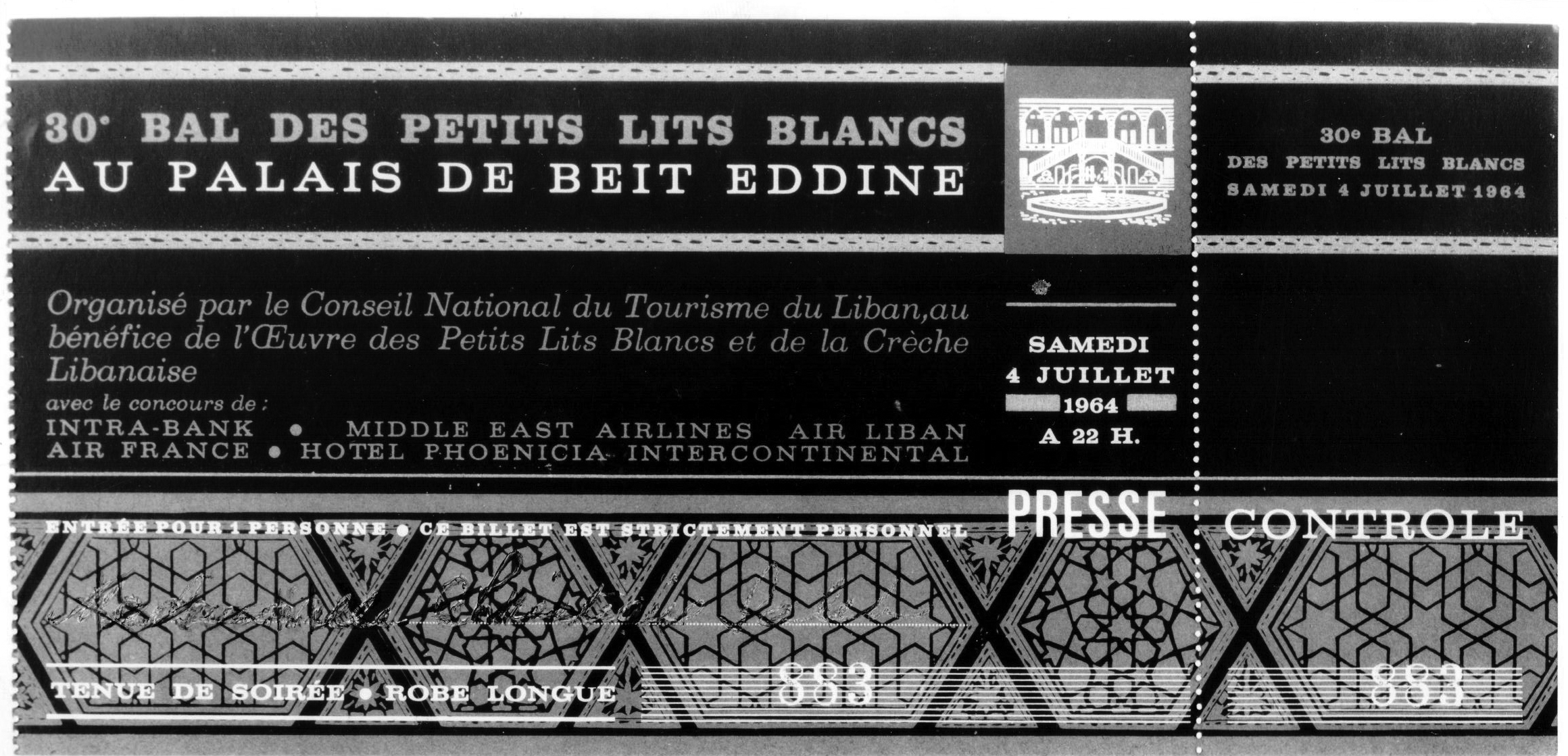

Another unforgettable moment in Lebanese fashion history, Challita says, is when the country hosted one of the grandest balls in modern history in 1964. Over the course of three days, the “Bal des Petits Lits Blancs” hosted such luminaries as Lebanese Princess Mona Solh, married to a Saudi prince, and French Vicomtesse Jacqueline de Ribes. “Beiteddine! Baalbeck! An afterparty that lasted until sunrise. The grandeur of it all left a massive impression on me.”

A press pass ticket to the 30th Petits Lits Blancs Ball on July 4, 1964. (Credit: L’Orient-Le jour archives)

A press pass ticket to the 30th Petits Lits Blancs Ball on July 4, 1964. (Credit: L’Orient-Le jour archives)

One of the most prestigious balls of the Parisian high society would raise money for sick children. “What many people don’t know, and what makes it a crucial event in Lebanon’s fashion history, is that Lebanon was the first country outside of France to have the honor to hold this major event,” Challita says, his eyes twinkling with excitement.

Does he ever grapple with the fact that he’s dedicating his time and energy to something that some Lebanese would regard as frivolous in the current context of the country, with many if not most struggling to pay rent, and having little money left for life’s luxuries or even the simplest pleasures?

In other words, what is the role of culture, specifically fashion, when a country is drowning, so to speak? Is the mere act of providing people with joy and distraction enough?

“Even through our hardships, we need to lift ourselves up,” Challita says. Rather than simply romanticizing the past, Challita believes the Lebanese need to delve into their identity and heritage to continue their legacy.

“We’re still the same people, we still have the same culture and talents,” he said. “Neither hardships nor war are going to erase our high-spirited heritage.”