A photomontage designed by Marc Mansour. (Credit: Marc Mansour)

Since the beginning of the crisis, the Lebanese lira has lost over 95 percent of its value. Inflation is exponential: a few days ago, the World Bank reported that Lebanon had experienced the highest year-on-year increase in food prices in real and nominal terms by the end of July. Gas prices have also exploded. The collapse is violent and far from over. In this context, a question often comes up: but how are the Lebanese managing?

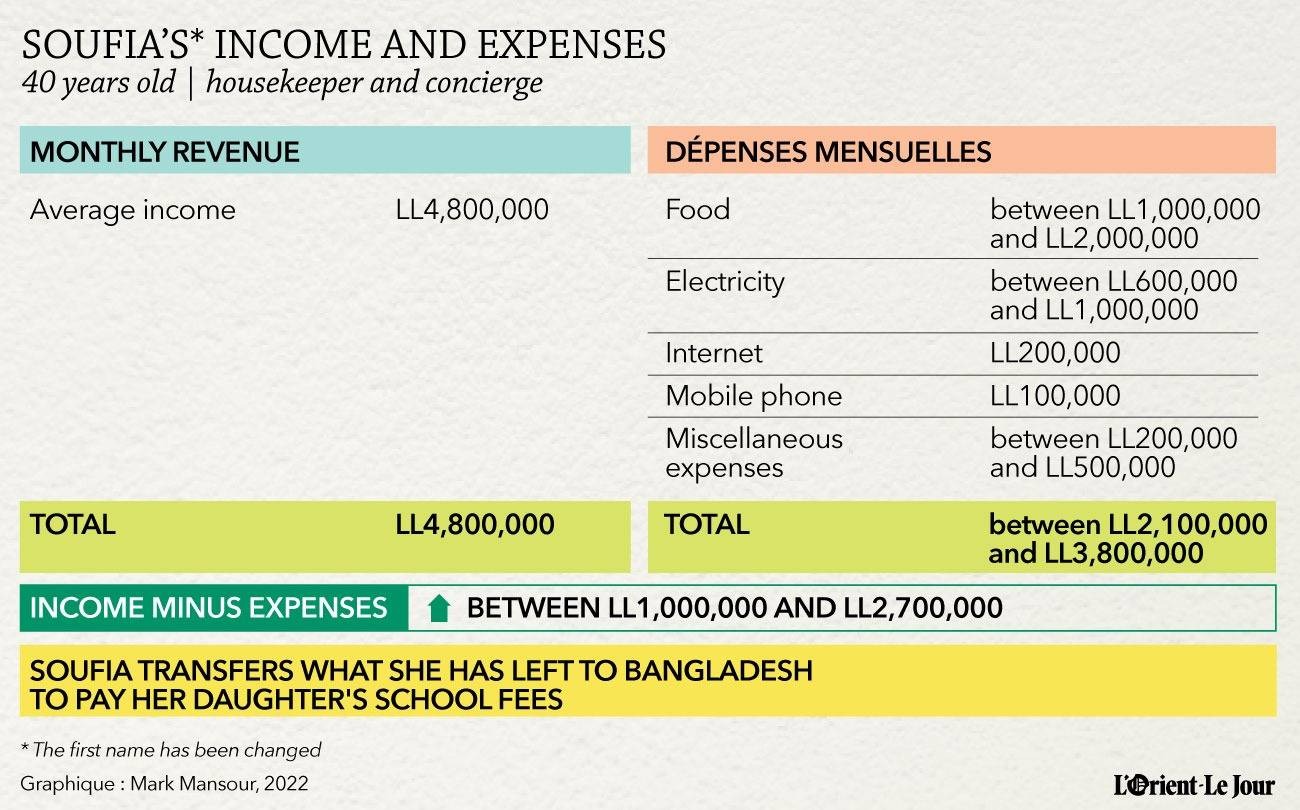

L’Orient-Le Jour asked this question to some of them. They agreed to share their stories. One of them is Soufia, a cleaning lady, who, despite her difficult job, is bending over backward to make ends meet in this compounded crisis.

She is not Lebanese, but she has been in Lebanon for more than 12 years.

Born in Bangladesh 40 years ago, Soufia* arrived in Lebanon in early 2010 after working for a few years in the Gulf. The youngest of seven siblings, she is the only one in the family to have emigrated, leaving behind her 15-year-old daughter, whom she had with her estranged husband.

Based in a residential area of Metn, Soufia works as a cleaning lady for several households and as a janitor of a building in a neighborhood that is neither upscale nor destitute.

She lives rent-free in a 20-square-meter studio on the ground floor of the building where she works, with her landlord’s approval.

It is a small space, but not cramped as she has skillfully equipped it with furniture and knick-knacks from here and there. She managed to get her hands a small fridge that is relatively quiet for its old age, and a desktop screen serving as a television.

“I was lucky to be able to equip myself properly before the crisis,” she said, apologizing for her broken Arabic.

A crushed standard of living

For Soufia, the collapse of the Lebanese economy since 2019 has smashed her admittedly modest standard of living, which was nonetheless acceptable and had allowed her to financially support her family.

“When the dollar was still at LL1,500, I used to earn about $600 to $700 a month by cleaning on a regular basis for six or seven clients. Today, I only have five left and I still charge LL60,000 pounds an hour,” she explained.

Her average monthly income is now reduced to LL4.8 million, or $150 at the rate of LL32,000 to the dollar, which represents nearly 25 hours of work per week for cleaning her clients’ apartments.

This is in addition to her obligation to be available at certain times for the needs of the building where she works as a janitor and where the owner can call her at any time.

“I’m thinking of raising my rates soon or asking to be paid in part in dollars (fresh),” she said — a measure that is becoming increasingly widespread in Lebanon, as well as in the cleaning business.

Before the crisis, Soufia earned enough to afford a plane ticket costing between $600 and $700, while also managing to put some small savings aside. Those, however, have dwindled away with the economic crisis.

Today, with the equivalent of $150 a month and the need to send whatever she can spare to Bangladesh to finance her daughter’s education, Soufia is now thinking of leaving the country.

“Everything is more expensive and the increase in telecom prices this summer made things even worse for me. My internet bill went from LL60,000 to LL200,000. For just over LL100,000, I keep my line with minimal credits and no 3G. I replaced my apartment fan, which was using too much power, with a small portable model,” she explained.

Sudden downgrading

In terms of food, the downgrading is brutal. “Before, I used to buy lamb meat, fish, chicken, pasta, Nescafé ... But all these have become too expensive, so I fall back on lentils, potatoes or zucchini — in short, everything I can buy at a good price at the supermarket,” Soufia said.

In terms of cleaning products, it’s the bare minimum.

“Sometimes some customers pay me more or give me certain products (mass-market goods) which have become quite expensive in Lebanese lira in the markets,” she said, pointing to a bag of tissues she recently received.

For medication, Soufia said she lives on the supplies she built up during her last visit to Bangladesh last year. For her, it is virtually forbidden to get sick, and with chronic pain, she has no other option but to grit her teeth.

“I should see a doctor for the pain in my foot, but I can’t,” she said.

Finally, for leisure, she said there is not much she can do. “I just walk around when I can, I pray, I keep busy," she summed up solemnly.

The picture Soufia painted is no exaggeration. Until a decree was issued in May, whereby small salaries were raised albeit disproportionately given the lira’s collapse, the minimum wage was still stuck at LL650,000 or $20 at the parallel market rates.

Ironically, by the beginning of 2021, this same minimum wage had depreciated ($72 according to the Lebanese research institute Information International, which used a rate of LL9,375 pounds to the dollar) to the point where it was worth less than that of Bangladesh ($95).

*The name has been changed.

This article was originally published in French on L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.