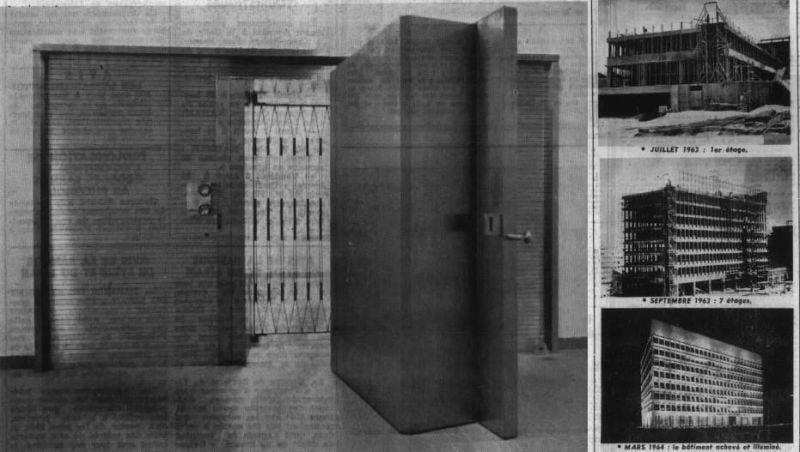

BDL's 80 cm thick vaults where 59.8 percent of the gold is kept. On the side, the construction of BDL Headquarters in1962-1964. (Credit L'Orient-Le Jour archives)

BEIRUT — With the economy still spiraling almost three years into the country’s financial crisis, much talk has swirled around the sale or collateralization of Lebanon’s gold as part of a recovery plan.

It’s worth noting that this debate has played out before during a different time and a different crisis. It also raises the question of why Lebanon has so much gold in the first place. With 286 tons, or 9.22 million troy ounces, Lebanon has the second largest store of the precious metal in the region, with about 40 percent of it being stored in the United States.

So, what was the original purpose of all this gold, and when and how did Lebanon acquire it?

The purchase of the gold is commonly attributed to former Banque du Liban Governor Elias Sarkis, who would later become president of the republic. This is a misconception as, while Sarkis was responsible for acquiring a significant portion of the gold reserves, 59.6 percent of the current reserves had been purchased before he was head of the central bank.

Although gold was used during Ottoman and French Mandate times, the modern traces of Lebanon’s gold are rooted back to the late 1940s.

At the time, the International Monetary Fund sought to tie the world’s currencies to the dollar through the Bretton-Woods system. Under this, dollars would be convertible to gold, with each ounce being worth $35.

Lebanon was admitted to the IMF on April 14, 1947, with a quota of $4.5 million, none of it paid in gold, rather in cash, according to the IMF’s 1947 annual report.

Historian Hicham Safieddine explains that “Lebanese officials invoked cultural and financially flimsy excuses to delay shipments of gold to the IMF in order to evade meeting their obligation of restocking Lebanon’s gold subscription quota.”

In 1948, Lebanon split from its monetary union with Syria after signing the Franco-Lebanon Agreement. Under this, the Lebanese lira would no longer be equal to or interchangeable with the Syrian lira; it would no longer be supported by French reserves.

This was due to the French franc’s volatility in relation to the US dollar, ripples of which were felt in the value of the lira.

Instead, Lebanon refocused its monetary policy on a favorable exchange rate with the US dollar.

To do this, Lebanon passed a law on May 24, 1949, under which the lira was equivalent to 405.512 milligrams of gold, and all notes were to be backed by 50 percent gold and foreign currency coverage, with the rest being covered by bonds and securities.

Decree 15105, issued a few days later clarified that the gold cover should be gradually raised to that level over the next four years.

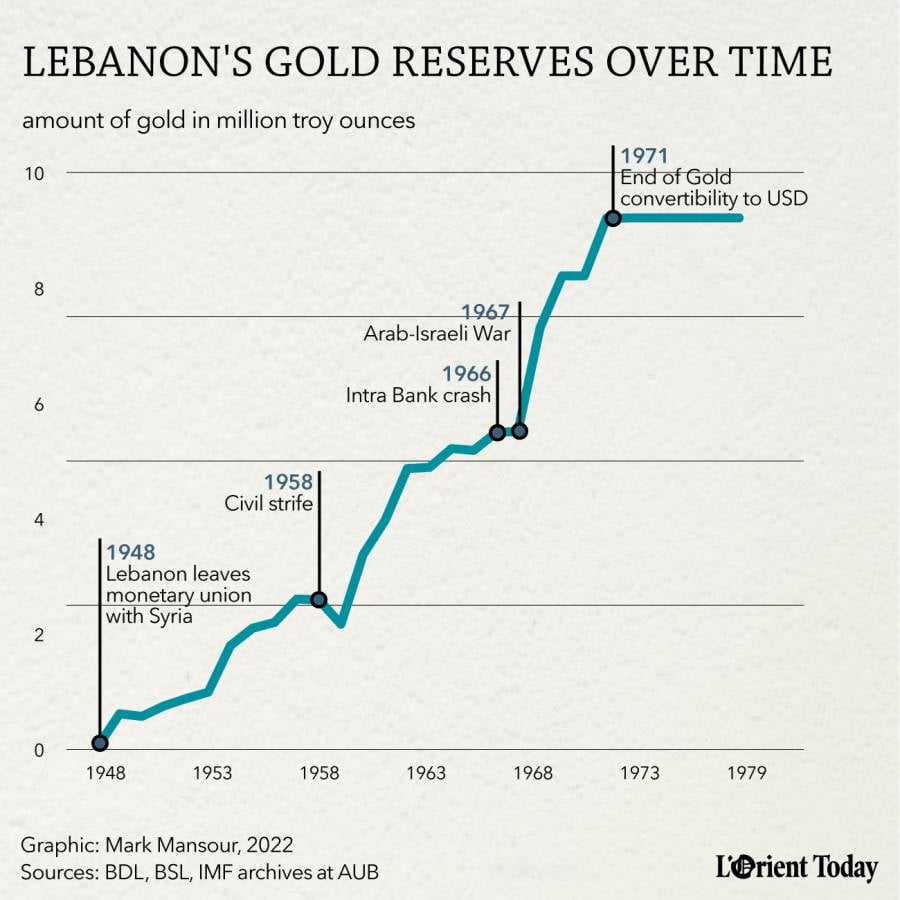

By the end of 1949, Lebanon’s gold reserves reached 620,000 troy ounces, and the country was able to raise its cover to 25 percent, and to 36 percent by the end of 1950. It was not until 1952 that a 55 percent parity was reached. By then, the reserves had grown to 870,000 troy ounces. In 1955, Lebanon had achieved 95 percent gold backing. The cover would fluctuate between 77 and 92 percent in the years that followed.

The country would increase its gold reserves to keep up with the growing amount of currency in circulation, which from 1952 to 1958 had increased from LL200 million to LL399 million. Therefore, the amount of gold increased to 2.5 million troy ounces in that year.

Lebanon bought its gold from either local, American, Swiss or British markets.

It was able to afford the gold by selling its French currency reserves. In the 10 years since the agreement, Lebanon sold 13 billion francs ($110 million at the time) worth of reserves, in exchange for 2.6 million troy ounces, or 82 tonnes, of gold worth $91.2 million, IMF and Banque de Syrie et Liban figures show.

Lebanon was also able to buy gold using an unlikely source — foreign aid. In at least one case, Lebanon used US aid to buy US gold. According to US congressional papers, in 1961, while Lebanon was under the leadership of then-President Fouad Chehab, the United States granted Lebanon $10 million worth of aid, which Lebanon used to buy the same amount in gold from the US Federal Reserve.

What aided the purchase of gold was Lebanon’s favorable balance of payments, meaning more money was coming in from abroad than leaving the country. World Bank figures from the 1950s and the BDL reports from the 1960s-70s show a positive balance of payments for most of these decades, despite a negative trade balance.

The reason for this positive balance of payments was Beirut’s position as a financial hub at the time, as well as remittances from Lebanese expatriates, and transit fees paid to Lebanon by pipeline companies for the use of its ports and refineries in Tripoli and Saida.

In the 1950-60s, Beirut became an intermediary between the European and Asian gold markets. Indeed, figures from BDL’s 1965 annual report noted that since 1961 Lebanon had been importing gold in huge quantities, amounting to 20 to 30 percent of its import balance sheet.

A declassified 1971 CIA handbook entry on Lebanon noted that “non-monetary gold enters the country legally. … However, most of the gold then leaves the country in the vests or luggage of ‘couriers’ and its export is not recorded in trade figures.”

The Lebanese market was one of the reasons why the Soviet Moscow-Narodny Bank opened a branch in Beirut to “sell Soviet gold on Lebanon's free market to finance wheat purchases from the United States and Canada,” The New York Times reported in 1964.

By that time, BDL had taken over the helm of running the country’s finances.

Prior to 1964, the job was managed by the privately owned French Banque de Syrie et Liban. After the shift to BDL, the gold was moved from BSL’s headquarters on Allenby street — where the Beirut Souks cinema is today — to the newly built BDL headquarters in Hamra. The gold was locked away behind a 17-ton door in an underground vault 80 cm thick, allegedly built to withstand a nuclear explosion. Lebanon had amassed about 5.5 million troy ounces of gold, as per BDL’s 1965 annual report, three years before Sarkis became governor of BDL in 1968.

Ottoman Imperial Bank later Banque de Syrie et Liban on Allenby Street. (Credit: Salt Library)

Ottoman Imperial Bank later Banque de Syrie et Liban on Allenby Street. (Credit: Salt Library)

Lebanon’s gold reserves helped it shield the lira against market shocks. For example, after the 1958 civil strife, gold reserves dipped by 420,000 troy ounces of gold. To replenish this, the country bought 1.16 million in the following year.

This would happen again in the wake of the Intra Bank crash in 1966, the Arab-Israeli war of 1967, and after the Israeli attacks on Beirut in 1968.

In this period, the gold reserves increased to 8.214 million troy ounces.

They ensured a stable exchange rate with the US dollar, which hovered around LL3 to the dollar before the war.

Lebanon’s last purchase of gold was in 1971; by then the reserve had grown to 9.211 million troy ounces. In that same year, Richard Nixon temporarily suspended the Bretton-Woods system convertibility, before formally ending it in 1973.

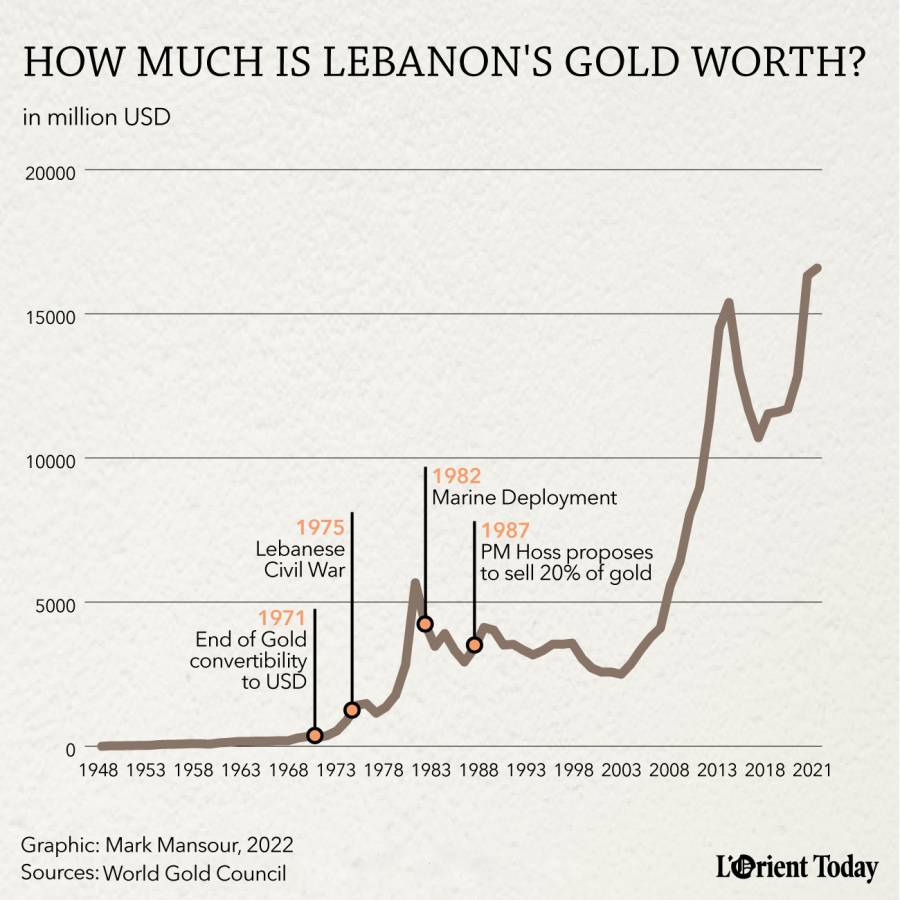

From then on, gold prices skyrocketed as they were no longer bound by the $35 an ounce rule. And so, the value of Lebanon’s gold reserves grew from $375 million in 1971 to nearly $1.5 billion at the start of the Lebanese Civil War.

Despite the Civil War erupting in 1975, Lebanon’s finances were initially kept largely intact. One year into the fighting, a 1976 US intelligence memo noted that the lira was still trading at LL2.70 per dollar, and that the currency still enjoyed 80 percent gold backing, with the “majority of these gold stocks … reportedly located abroad.”

Moreover, the country even managed to restock gold in 1979 by 3,850 troy ounces, by buying back from the International Monetary Fund its share of gold distributed to its members.

Additionally, Lebanon still had a positive balance of payments as the Civil War entered the 1980s. In a Financial Times article dated August 1982, an anonymous senior Lebanese banker attributed this to remittances from Lebanese living abroad, as well as foreign funding coming in to support militias involved in the war.

By then, gold prices had jumped from $160 an ounce in 1975 to $376 in 1982, valuing Lebanon’s gold at close to $4 billion.

With the US Marine deployment in Lebanon, talks began to swirl around rebuilding the country and how it could be financed. Regional and international donor conferences only offered paltry sums toward the estimated $13 billion reconstruction bill.

Soon, focus began to shift to how the gold could be utilized to rebuild Lebanon. However, the central bank governor at the time, Michel El Khoury, opposed this.

In a declassified US intelligence assessment, Khoury noted to the American envoy his reluctance to spend the country’s reserves on reconstruction, “on the grounds that whatever is rebuilt can easily be destroyed in another round of fighting.”

As he predicted, hopes for peace were dashed. Meanwhile, the Lebanese currency began to slide against the US dollar as the balance of payment turned negative in 1983.

BDL attributed this to low oil prices, meaning fewer remittances. The press noted that with the Palestinian Liberation Organization having departed to Tunisia, there was less foreign funding coming into the country.

Figures from the central bank noted a deficit of $533 million in the balance of payments in 1983 compared to a surplus of $238 million a year before.

To counteract this trend, BDL began using its foreign exchange reserves to prop up the currency in the market. Foreign currency reserves, which by the end of 1982 amounted to $2.6 billion, had decreased by $613 million “under double pressure from demands from banks and the public sector,” BDL’s 1983 annual report noted.

Out of fear that gold might be used to prop up the lira, and to reinforce confidence in the currency, a law was passed on Aug. 19, 1986, preventing the central bank from dipping into the gold reserves without the permission of Parliament.

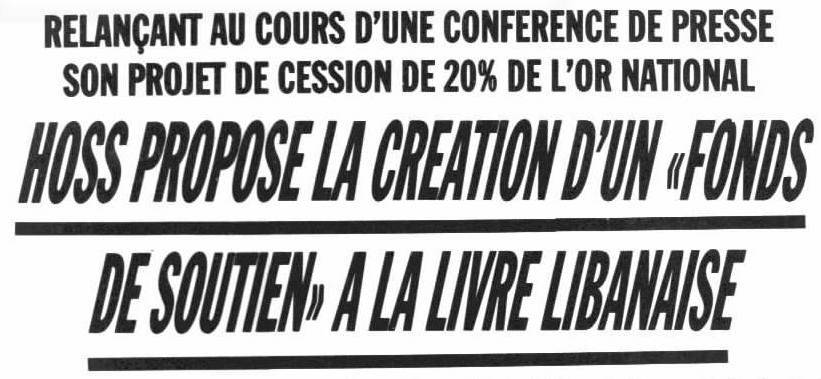

But by January 1987, the currency had tumbled to LL17 per dollar, later dipping to LL220 in August of the same year. To combat this, Lebanon’s then-Prime Minister Salim Hoss proposed selling 20 percent of the gold to support the currency. AP quotes him as saying that such a measure would “ensure us something like $800 million for a special fund to support the Lebanese pound [lira].”

L'Orient-Le Jour headline reading "HOSS PROPOSES THE CREATION OF A 'SUPPORT FUND' FOR THE LEBANESE LIRA."

L'Orient-Le Jour headline reading "HOSS PROPOSES THE CREATION OF A 'SUPPORT FUND' FOR THE LEBANESE LIRA."

This proposal received opposition from experts, with some describing it as “slapping a bandage on a man already dying.” They noted that the drain on the reserves was mostly due to continued subsidies on gas and wheat, which were being smuggled due to the depreciation of the Lebanese lira — a similar scenario to today’s crisis, and much like today, broader reforms were needed.

The proposal was also opposed by then-President Amine Gemayel.

According to a New York Times report, the sale hinged on the formation of a new cabinet, which never happened.

Lebanon was already exhausting its foreign currency reserves to try to maintain the stability of the currency, reportedly reaching a low of $200 million in 1987.

Edmond Naim, governor of BDL at the time, told AP that this shortfall “had dangerously minimized the central bank’s ability to help support the Lebanese pound.”

Today, some see the gold sale as a foregone conclusion.

Financial analyst Mike Azar told L’Orient Today that, law or no law, the gold is already spent.

“In the end, BDL and the political branches who oversee it found a way around the law and around public opinion. Sure, the law says the gold cannot be used in any manner,” he said. “But what happens if you borrow so much debt and incur so many losses that you become insolvent, and all of your assets (of which gold is one) are needed to cover those debts?”

He added that signs of the gold’s utilization are evident in the recovery plans stretching back to 2020.

“All of the financial recovery plans and figures since 2020 have earmarked the gold to cover BDL losses,” he said.

Azar noted that the more than $60 billion in losses reported on the BDL balance sheet “would be higher if the gold did not exist” and that if the gold were removed from the balance sheet, it would require a more severe “haircut” on large depositors than is currently proposed.

Amid attempts by some elected officials to prevent the sale of the gold, Azar said,

“If the change MPs do not want the gold to be used to cover BDL’s losses, they would propose a law expressly prohibiting the gold from being used in this way on its balance sheet, with all of the fallout that involves.”