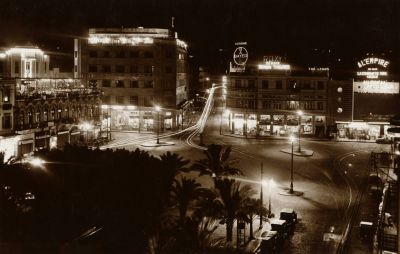

Martyrs' Square in Beirut, at night, in the 1930s. (Credit: Photo Sport, coll. Gaby Daher)

These words go to those who want to kill Beirut. But also, to those who fear that Beirut might indeed be killed, who believe that Beirut may be a mortal city. A city like Beirut cannot die. It might transform, no doubt. Might it be taken hostage? So what? Beirut spans, not years, not even decades, but Beirut spans centuries.

The flame of life burns inside Beirut, and those who dare touch it burn their fingers. This flame burns brightest at night when the setting sun finally finishes teasing the intimacy of the city’s homes, when the glaring glow makes way for a soothing light-dark hue, when the horizon is adorned with a turquoise dappled with purple that makes poets cry, just before the night opens the curtains of the universe like a theater. That’s when Beirut’s will-o'-the-wisp lights up, that’s when a city wakes up, rushing to slap destiny in the face, a city that makes noise to scare death and has fun making fun of itself.

In the beginning there were taverns and hakawatis (storytellers) reserved for men only. But beginning in 1899, cinemas were opening up for women, making the night less of an underworld. The first movies were screened on white sheets hanging in the air. It was at the Zahrat Souriya (Fleur de Syrie) theater, at the far left of this picture, that the Parisiana music hall, opened in 1928, unfolds in a bath of light. From Zahrat Souriya to Parisiana, it was a significant name change that Samir Kassir judiciously pointed out: Beirut had opened up to the West. It is true that the French mandate played a major role in this, but the mandate would have only birthed a small change if it had not been for the hard work and magic strokes of the religious brotherhoods, and most of all the Jesuits.

In the 1930s, Beirut wanted to be like Paris from all its heart: cinemas, cabarets, music halls, bars, outdoor cafes; the night has now become a full day that begins at dusk and continues until the first rays of dawn. Beirut is wrapped in light and neon at a time when other Arab capitals — apart from Cairo — are falling asleep in modest silence. Two neighborhoods stand out: the Avenue des Français and Martyrs’ Square.

We stand here at Martyrs’ Square, near Hotel Savoy that houses the offices of Le Jour daily among others, just west of the square. The camera is placed on a tripod, facing southeast, with a long exposure time set to capture the light of the night and make the picture a postcard published by Photo Sport. The result is a little marvel. If you listen closely, you can hear Beirut breathing, you can hear the intertwining voices of artists and orchestras mingling with the sounds of applause, the clattering of cutlery on porcelain plates and the hubbub of the crowds. The picture even exudes a particular fragrance, a bitter-sweet mix of hookah and cigarette smoke, embers of burning coal and grilled food, marine air, jasmine and orange blossoms: this is the sensuous smell of the Beirut night.

There are images that withstand the test of time, and this is one of them. We can roughly place it just before the disappearance of Le Royal cinema theater that we see on the right, with a sign bearing the name of its little brother L’Empire. Le Royal will be destroyed in the fall of 1946 to open the Bechara El-Khoury boulevard. The picture also dates back to before the inauguration of the Hollywood cinema on April 12, 1943, at the old location of the Aref restaurant on the ground floor of the Sursock building, the modern building we see on the left, pictured before the bankruptcy of this same Aref restaurant in the early 1940s.

But the picture must have been taken after the opening of the Roxy cinema (early 1934), and specifically after the great collapse of the building that housed Kawkab ech-Chark café (March 1934), which was replaced years later by the two-story building in the middle of the picture, known as the Tabet building overlooked by the Roxy sign.

We thus find ourselves between the years 1936 and 1940. Looking at the abundant lighting and the models of the cars parked in Martyrs’ Square, the picture may have been taken during the three last years of World War II.

The movie being screened at Roxy left little mark on the history of cinema. Released in 1932, “Tomorrow at Seven” depicts the story of a serial killer called the “Ace of Spades.” The owner of the Roxy, Gabriel Murr, loved to scare his audience. In any case, he went all out to attract the audiences: the neon on the Tabet building had to be changed regularly to reflect the programming, sometimes every week, which was also the case for the ads of L’Empire, the magnificent Art Deco building at the far left that is bathed in light. L’Empire first started out as a theater in 1927, to quickly be taken over and developed by the pioneers of cinema in Lebanon, Nicolas Cattan and Georges Haddad, who turned it into the most durable of Lebanese theaters.

Abou Afif, a place without doors

Beirut at night in the 1930s is a profusion of illuminated advertisements: Aspirine Bayer, Thé Lyons, Ovaltine. Beirut at night in the 1930s is this iconic restaurant Abou Afif, located just opposite, at the left corner of the Tabet building on Damascus street. Abou Afif has come a long way: it was because of the reckless work he undertook at his newly-rented place in Kawkab ech-Chark building that the whole building collapsed, leaving dozens of victims. But Abou Afif had connections, and pretty soon, his restaurant became a hot spot for the night owls leaving one of the many cinemas scattered across the area. Abou Afif never installed a door for his restaurant, even during World War II: What good would a door have been for a restaurant that never closes?

Beirut at night during that time was thousands of night owls that supported taxi drivers, waiters, bartenders, dishwashers, chefs, cooks, café owners, vendors of foul (a dish of fava beans), fruit vendors, the Mirza café of Haouz es-Saatiyeh distributors of sahlab (a sweet milk pudding drink) at the corner of Foch avenue, the roast meat seller on Gouraud street, the tobacco shop of Caracol el-Abed, and so on.

Beirut at night in the 1930s is the vehicles, which we only see as streaks of light frozen in time by the photo exposure. These white strikes on the silver emulsion give an idea of the number of vehicles and the direction of traffic; if a tram stops for just a little longer, it leaves a spectral image for future generations.

And it is this city that has gone through so much and that never dies, that some believe has been brought to its knees? No, it’s not enough to ruin a people: this people survived famine before making their capital the Paris of the Middle East. Nor is it enough to destroy the stones; these have been destroyed seven and ten times, and by all means. It’s not enough to frighten: four centuries of Ottoman oppression were not enough. It’s not enough to scare away the inhabitants: they always come back in the end through its open port like the arms of a mother that awaits her children. No, Beirut will not die.

*Thanks to Gaby Daher for this magnificent postcard from his collection.

Author of Avant d’oublier [Before forgetting] (L'Orient-Le Jour editions), Georges Boustany takes you, every two weeks, to visit Lebanon in the last century through a photograph of his collection to discover a country that faded away. The book is available worldwide on www.BuyLebanese.com and in Lebanon on (WhatsApp) number +961 3 685968

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury.