FILE PHOTO: The International Monetary Fund (IMF) logo is seen outside the headquarters building in Washington, U.S., Sept. 4, 2018. (Credit: Yuri Gripas/Reuters)

BEIRUT – Lebanon’s negotiations with the International Monetary Fund are back on track after more than a year's hiatus. In that time, the Lebanese population has sunk further into poverty as the lira lost 90 percent of its value, consumer prices tripled, and most of the subsidies on essential items including fuel and medicine were removed.

“This is Lebanon’s last chance before it collapses and becomes a failed state,” predicted Olivier de Schutter, United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, during his recent visit.

Officials in the newly formed government, despite the political blockage that has stalled the cabinet’s work, have expressed hopes that they will stabilize the economy by reaching a preliminary deal with the IMF before the end of the year.

However, others have expressed doubts.

Henri Chaoul, a former adviser to the finance minister in previous Prime Minister Hassan Diab’s government, told L’Orient Today that he believes the process of IMF negotiations is "just for show" and that the government is incapable of making any progress on the file.

In 2020, Chaoul played an integral part in drafting the government’s financial recovery plan and was a key member in the negotiating team with the IMF. He resigned five months after taking the advisory position, frustrated not only with the lack of progress, but also with the actions of some officials who he said went as far as undermining the negotiations from within.

Deputy Prime Minister Saade Chami, himself a veteran of the IMF, said in a recent television interview aired by LBCI that “Lebanon is going through an exceptional multi-faceted crisis, the kind I have never seen in my 20-year career at the IMF.” Chami was appointed to Mikati’s cabinet to deal with the IMF, negotiate with creditors and work on the restructuring of the banking sector, among other pressing issues.

Chami noted that Lebanon has applied to the IMF’s Extended Fund Facility (EFF) program, designed to provide assistance to countries experiencing serious payment imbalances. It is typically approved for periods of three years but can be extended for one extra year. The EFF can subsequently be repaid over four to ten years in equal semiannual installments, in contrast to other shorter-term financing options extended by the IMF.

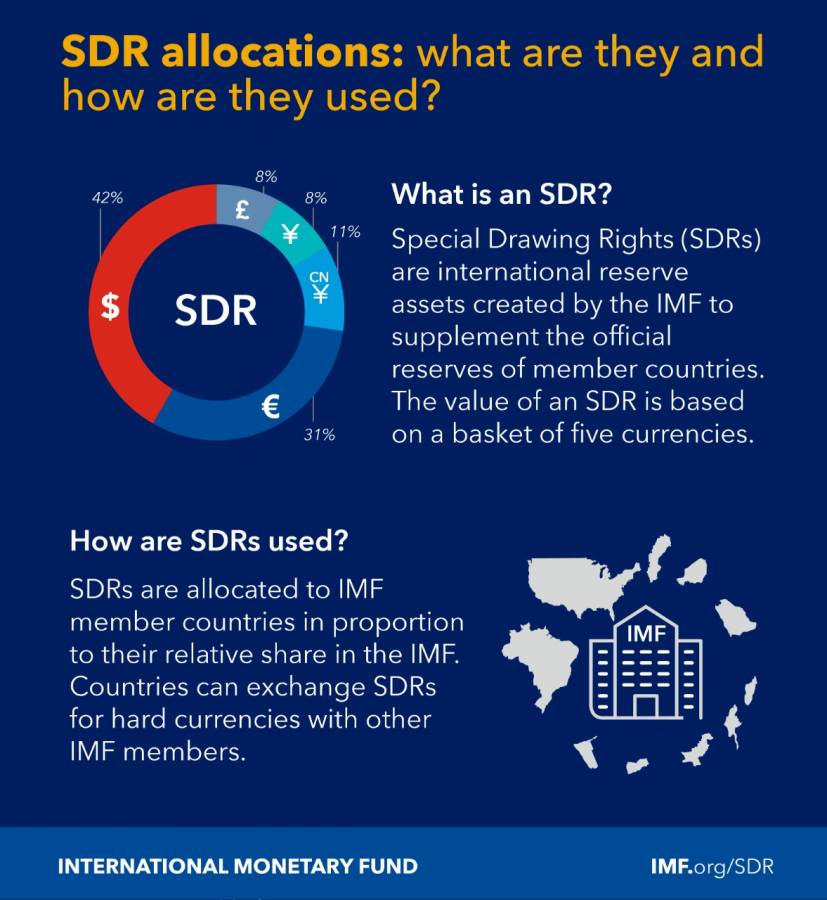

The amount of financing Lebanon can access per year is determined by its Special Drawing Rights (SDR) quota. Upon joining the IMF, every country must pay a one-time “membership” fee (or quota) based broadly on its relative position in the world economy. These fees from member countries give the IMF the necessary funds to lend to faltering states. The quotas are revised periodically by the IMF’s Board of Governors, and they ultimately determine the country’s voting power and later its access to IMF financing. The quotas are measured in SDRs. SDRs are a unit of account used by the IMF and other international organizations, their value is based on a basket of five currencies — the U.S. dollar, the euro, the Chinese renminbi, the Japanese yen, and the British pound sterling. One SDR is currently equivalent to $1.40.

Under the EFF program, Lebanon can potentially access 145 percent of its annual SDR quota. This number currently stands at 633.5 million SDRs, so 145 percent of it is equivalent to $1.28 billion. Over a three-year period, the total amount under normal access rises to $3.8 billion; over a four-year period, it becomes $5 billion. Chami also implied that exceptional access may be offered on a case-by-case basis, and that could increase the overall size of the facility to $7-8 billion.

Reaching a deal with the IMF is important not only to allow Lebanon to access these funds, experts said, but also to signal to the international community that the country is serious about reforms. While the IMF funding on its own will not be enough to make a significant dent in the crisis, it could pave the way to unlock other potential aid; more importantly it might reassure investor confidence.

“We can do it without the IMF, but with the help of the IMF it will be quicker and will add more credibility,” explained Sami Geadah, previously the alternate executive director at the IMF Board representing Lebanon, during a recent LIFE Lebanon webinar. The IMF assistance will help jumpstart the economic recovery more quickly, he said, but the most important point for the whole program is to reach debt sustainability. Debt sustainability means the government can meet its future obligations without the need for future assistance.

Geadah continued that the IMF’s previous target number for debt sustainability for emerging countries was more rigid, being set at 70 percent of gross domestic product. However, recently the IMF has been rolling out a new methodology that takes into consideration several other factors like maturities, debt service level and the identity of the debt holders. But, whatever the target number, he added that for Lebanon’s debt to drop to acceptable levels it needs to be reduced substantially.

What are the prospects for the talks this time?

The disagreement around a unified number for the financial sector losses was the main reason behind the breakdown in talks between the Lebanese government and the IMF in 2020. The dispute led to Chaoul’s resignation, which was shortly followed by the departure of Alain Bifani, the director general of the Finance Ministry.

The government at that time estimated the losses at more than $70 billion. But Banque du Liban, the banking industry, and some members of Parliament, firmly contested it and claimed their calculation showed the size of the losses to be only a quarter to a half of the IMF’s number.

“Officials may look like they are cooperating, but at any moment they can change strategy. Look at what happened in 2020, everyone was working with us on the plan until they turned on us,” said Chaoul, adding, “Riad Salameh, the banks, and officials who are in bed with them do not have any incentive for finding a way out, [and] it is the country who has been bearing the brunt.”

At the moment, with the government of Najib Mikati paralyzed by a political dispute over the future of the Beirut port blast investigation and its lead investigator, Judge Tarek Bitar, it appears to have shifted its priorities to survival first.

But Mikati has made a show of being adamant about moving forward with the IMF talks. In his government’s ministerial statement, he made the IMF negotiations a priority. He announced the formation of the negotiating team headed by Saade Chami, Finance Minister Youssef Khalil, Economy Minister Amin Salam, Banque du Liban governor Riad Salame and Charbel Kardahi and Rafik Haddad--two advisers to President Michel Aoun.

Mikati went further and announced during an economic conference in Beirut on Nov. 9 that Lazard, the asset management company advising the government, will have an amended financial recovery plan ready by the end of the month. But most importantly, and to the surprise of observers, he proclaimed that the government has for the first time provided the IMF with a unified number.

However, he did not disclose what this number is and how a consensus around it suddenly emerged.

Mikati and Chami both asserted that Banque du Liban has been cooperating and has sent all the required documents to the IMF, but in a recent interview with Reuters, Riad Salameh acknowledged that they had yet to deliver the data to the IMF, and, contrary to what Mikati announced, it seems that there is no unified number.

A Finance Ministry spokesperson told L’Orient Today that the ministry staff have no knowledge of this number, and that the Prime’s Minister’s office is responsible for the file. Representatives of Mikati and Chami could not be reached for comment.

Even assuming that the government can reach a consensus around the size of the losses, talks with the IMF are just starting and before a memorandum of understanding can be sent to the board to be signed, Lebanon must work on fulfilling certain preconditions. Some of the reforms will take time and the IMF will be monitoring their progress, such as fiscal reforms and banks’ restructuring, but others can be immediately implemented; such as capital controls, exchange rates unification, and governance through audits of Banque du Liban and Electricite du Liban.

Chami also explained in the LBCI interview that no funds will be released before the IMF board signs off, and before it signs it needs to see clear progress on the above-mentioned reforms. The disbursement of the funds should follow and under a best-case scenario this is not expected to take place before the end of the first quarter of 2022.

The controversy around the unified financial losses number is one major roadblock to progress, but also important is the paralysis of the government since Oct. 12 amid a dispute between political blocs over Bitar’s role in the port investigation. Aoun and Mikati have voiced hopes the government will meet soon but, pending evidence to the contrary, paralysis seems the order of the day, and this will keep pushing back any potential deal.

While Chaoul sees the scenario as just a repeat of 2020, officials have attempted to strike an optimistic tone.

“We are in a difficult situation, but there are solutions,” Chami said, “I don’t believe anyone can forecast [that] it will take us nineteen years to recover. I say it will maybe take us closer to two-to-three years.”

“This is Lebanon’s last chance before it...