Marwan Kaabour, author of "The Queer Arab Glossary." (Credit: Spyros Rentt)

You are a graphic designer and visual artist, as well as a queer activist. Growing up in Beirut, what was your first contact with the LGBTQ+ community in a country where their rights are flouted at best?

My cousins, who were about ten years older than me, started going out in Beirut in the early 2000s and often told me about the belly dancer Misbah.

There were no smartphones back then, but just the idea of a male belly dancer entertaining people at parties fascinated me. It was the first time I’d heard about a queer aspect of my city, without really having the words to describe it or even understand it.

On a more personal note, and I talk about this in the introduction to my book, I was a pretty mild-mannered kid growing up, and people used to call me “Foufou” [a derogatory term meaning effeminate in Lebanese dialect] in the street. At that point, I began to question the significance of this word and what it meant in relation to my identity and behavior.

This experience led me to understand that I was a queer person even though, as I said earlier, I didn’t have the vocabulary to articulate it.

Once you’d made that realization, what was it like growing up queer and gay in Beirut?

It’s always complicated when you’re Lebanese, and I’m not making this up. But I was lucky to have two artistic and, above all, progressive parents. The most fabulous thing was that they never made me feel guilty for my differences, for the fact that I was different from other boys my age, which was obvious from a very early age.

In fact, I was the complete opposite of my brother, even though we were brought up in the same way and environment. On my father’s side, the family is rather conservative, while on my mother’s side, the family is more matriarchal and open, so I naturally gravitated toward that side.

Even though I never really had a problem with my father’s family, I very quickly realized that I had to tone down this “queer aspect” of myself, if you can call it that.

The most paradoxical aspect was that heterosexual boys who had known me since childhood and grown up with me would protect me when other boys from other classes made derogatory comments about me. But that was before I really understood my queer identity.

So it wasn’t until I was 16 that I went online and talked to boys, without really managing to act on it or meet them.

I had to come to grips with this whole unknown world before taking the plunge at the age of 18. Before that, I just thought it was a phase and that it would pass.

Before “The Queer Arab Glossary” project, what were the first queer slang terms you came across?

The personal construction of my identity necessarily involved these words which, although often formulated with a homophobic connotation, helped me understand how queer language is used more generally in our region.

Without knowing what they meant at the time, I quickly realized that they had something to do with the way I spoke, walked and moved.

Then there were more obvious words, such as “mukhannat,” which also means effeminate, and is a very old Arabic word. But the most interesting for me was the Turkish word “Tobçi,” which literally means “fagg*t.” It was no longer about the way I behaved, but rather about my identity.

I’m fascinated by this word because linguistically, in Arabic, it doesn’t really have a meaning. It’s a word inherited from the Ottomans, as evidenced by the suffix “çi” pronounced “ji,” and then I discovered that “tob” is an old Turkish slang meaning homosexual. Then there’s the word “naem” [soft, in Arabic], which is the bourgeois way of referring to a homosexual, particularly when he belongs to that social class.

Tell us about the “Takweer” platform you created on Instagram in 2019, which led to the creation of your book.

“Takweer” is a digital project where I collect, archive, research and celebrate queer narratives in Arab history and pop culture.

I launched the platform in September 2019, originally as a research space to explore ideas and themes I was passionate about, and mostly because I’m obsessed with anything related to collecting and categorizing.

Without realizing it, I was in the process of creating an archive of queer history that had long been invisible in our culture.

I dig through articles, books, films, TV content, magazines, Arab artworks and even memes on social networks to extract queer narratives that I contextualize and then share on “Takweer” [in Arabic and English]. Today, the page has over 22,000 followers on Instagram, and I believe I have succeeded in creating a space for broad exploration that leads to more targeted projects, of which “The Queer Arab Glossary” is the first.

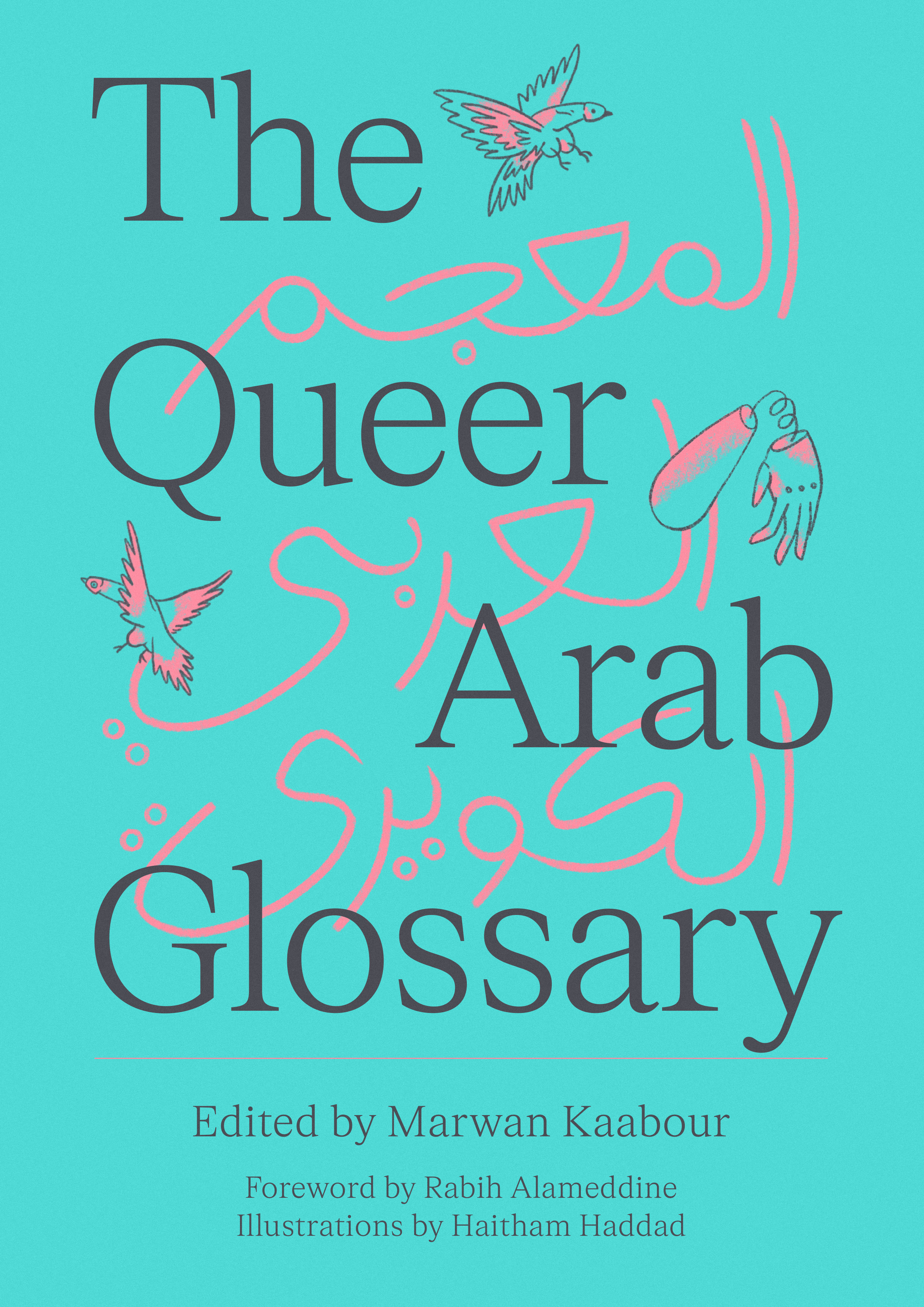

In “The Queer Arab Glossary,” you use regional slang to map out the queer language associated with the Arab world. As someone who has already worked on several projects, was it an obvious choice to turn them into a book?

Books are what I enjoy doing most, especially as it’s a format I’ve mastered and with which I can really express myself.

I also wanted to create a reference work that could find a place in personal and academic libraries for future generations. That was the primary aim of this project, which I also saw as an extension of the rich tradition of Arabic glossaries that I discovered as a child.

By formalizing these words and compiling them into a dictionary, I wanted to transition from the informal to the formal, as in all disciplines and fields.

Contrary to what is often said about the rise, or even the apogee, of digital technology, I truly believe in the durability of books. They will exist forever, against all odds.

(Credit: Haitham Haddad from the book)

(Credit: Haitham Haddad from the book)

How did you go about researching and compiling these terminologies?

As I said when I created this glossary, the idea was really to give a degree of seriousness to these words, which deserve it.

Through “Takweer,” I’m in constant contact with subscribers, many of whom speak Arabic dialects I’m unfamiliar with. They often use queer slang, and I ask them for explanations.

To compile the first terms in the glossary, I asked subscribers to suggest words they used or knew, specifying the country or dialect associated with each word and providing as much context as possible.

I repeated this exercise several times, which enabled me to gather a set of initial data, which I then organized in a fairly extensive Excel spreadsheet. I also conducted individual interviews with people from different geographical contexts.

We went through the list compiled for each area and discussed each term. I made sure that I spoke to people from different areas, but also from different socio-economic backgrounds and with different identities.

I continued these interviews until each term was properly contextualized and nuanced. I then translated all the entries myself.

The final stage was the crucial intervention of Suneela Mubayi, the glossary’s editor, who gave each term the necessary historical and cultural depth, while further refining the translations and language.

(Credit: Haitham Haddad from the book)

(Credit: Haitham Haddad from the book)

How would you describe this book? Is it a dictionary, a collection of essays, or both?

My vision for the project evolved as it developed. Initially, I intended to create a small glossary of terms, but with over 300-word submissions coming my way, it soon became clear that the project’s scope was much greater.

It was essential for me to situate and contextualize the book in today’s world, adopting different points of view.

Hence my call for diverse Arab voices, able to delve into the themes of language, slang and queerness from their unique perspectives and areas of interest.

Writers, musicians, researchers, poets, translators and musicians, including Saqer Almarri, Nisrine Chaer, Sophie Chamas, Rana Issa, Adam Haj Yahia, Mejdulene Bernard Shomali, Hamed Sinno and Abdellah Taïa, all come from different parts of the Arabic-speaking world. Their diverse experiences make it possible to truly map the nuances of Arab queerness.

What would you say to our readers, some of whom might be hostile to the LGBTQ+ community and for whom a book like this might arouse a form of fear?

I have a lot to say to them: Based on our shared history and language, we know that queer people, or those who don’t fit into the very strict parameters that you have defined as normal, have been around as long as you have.

We’re not here to change anything about your way of life, attack you or even demand anything you don’t want for yourselves.

All we ask is that you be open and listen. We want to be able to sit down together and have conversations without resorting to violence. And you need to know that queer people exist around you, close to you, in your families and sometimes even in politics.

So there are two options: The choice to break the fear, [a fear] based on a tactic by failing governments to make people believe that all the ills of a country are due to these minorities, or the choice to hate and live a life where hate thrives in your soul.

How does it feel to be able to launch this book in Beirut this summer?

It means a lot to me. Beirut is home. It’s where I got to know myself, where I discovered my culture and language.

This book is as much a labor of love for my community as it is for the environment that shaped me. It also represents the experiences shared with my friends back home. Being able to come and celebrate this love letter in my hometown, in the presence of my family, friends and colleagues, means the most to me.

I’m excited that the knowledge encapsulated in this book can coexist with all the other sources of knowledge in my country and the wider region, and I hope we can learn from each other.

The book is available on Amazon.

The book is available on Amazon.

“The Queer Arab Glossary,” published by Saqi Books, is available on Amazon.

This interview was originally published in L'Orient-Le Jour, translated by Sahar Ghoussoub and edited by Yara Malka.