(Credit: Jaimee Haddad)

The Khinshara qurban

The bakery smelled of yeast and orange blossom. Outside, Khinshara, a village located 30 kilometers northeast of Beirut in the Metn area, was not quite awake yet. It was 10 a.m., and the qurban [sacrifice in Arabic; the bread used for communion in the Orthodox Christian churches of Syria and Lebanon] makers were already preparing their second batch of dough.

The bakery smelled of yeast and orange blossom. Outside, Khinshara, a village located 30 kilometers northeast of Beirut in the Metn area, was not quite awake yet. It was 10 a.m., and the qurban [sacrifice in Arabic; the bread used for communion in the Orthodox Christian churches of Syria and Lebanon] makers were already preparing their second batch of dough.

They started mixing the yeast, flour and other ingredients at 7 a.m. The name “qurban” comes from the Syriac term “corpuno,” which means thanking God, especially after communion.

In Lebanon, two ovens produce this light brioche and sweet wafer: The one in Khinshara, which some say is over a hundred years old, and its annex in Zahle, in the Bekaa.

The qurban holds a special place alongside the other elements that define the character of Khinshara, a village of fewer than 3,000 inhabitants.

In Khinshara’s bakery, making qurban is simple and, above all, manual.

“The secret of its success lies in the fact that our qurban is made by hand, whereas other manufacturers use automatic machines, which don’t work as well,” said Ibrahim Houssine Brik, who, with over 20 years of experience, is the main supplier of this bread in Lebanon and the Middle East.

The mouwaraka of Amchit

This is a story about young women. More specifically, the daughters of the Zgheib family in Amchit, a coastal town between Jbeil and Tripoli. These women run a bakery, a furn, which they have named Furn al-Sabaya (the girls’ bakery), where the two sisters and their cousins work like bees in a hive to prepare mouwaraka, a crispy and sweet Amchit specialty.

This is a story about young women. More specifically, the daughters of the Zgheib family in Amchit, a coastal town between Jbeil and Tripoli. These women run a bakery, a furn, which they have named Furn al-Sabaya (the girls’ bakery), where the two sisters and their cousins work like bees in a hive to prepare mouwaraka, a crispy and sweet Amchit specialty.

Mouwaraka is a “puff pastry” (hence the name mouwaraka, from warak, meaning leaves) shaped into a spiral and filled with a stuffing made from crushed almonds and walnuts.

“As in all Mediterranean countries, this is the cuisine of mothers, whose recipes are often kept and passed down within the family,” explained Lorenza Zgheib.

However, Lorenza thought her mother’s recipe was too fatty and sweet, so she decided to put her twist on tradition. “I started looking for an alternative recipe that was healthier and more nutritious,” she said.

Today, Furn al-Sabaya offers a mouwaraka that is “nutritious, light and crispy, while retaining its original shape.”

Its light pastry and almond and walnut-based filling make it an ideal dessert for diets aimed at reducing the risk of several illnesses, particularly cardiovascular disease. In this way, the Zgheib women have succeeded in reviving an almost forgotten Amchit specialty.

The sfiha: A gourmet bite from Baalbeck

In the bakery/butcher’s shop in the Tour du Soleil in Baalbeck, the preparation of baalbakiyeh sfihas is a composition for percussion. Baalbakiyeh sfiha, a specialty of Bekaa’s capital, is a square bite filled with mutton, onion, tomato and spices.

In the bakery/butcher’s shop in the Tour du Soleil in Baalbeck, the preparation of baalbakiyeh sfihas is a composition for percussion. Baalbakiyeh sfiha, a specialty of Bekaa’s capital, is a square bite filled with mutton, onion, tomato and spices.

It’s a crispy little square that melts in the mouth when the meat and tomato juices soak the pastry after baking. Hence, the very appropriate combination of bakery and butchery.

According to Ali Chabchoul, owner of the Tour du Soleil bakery/butchery, the sfiha baalbakiyeh is unique and cannot be found anywhere else.

The mujadara hamra, a delicacy from south Lebanon

The mujadara hamra, a rustic delicacy from south Lebanon, is a stew with finely chopped onions, local olive oil, boiled red lentils and bourghoul.

In Srifa, a village in southern Lebanon, the household’s women gathered for the revered tradition of preparing this dish. In the pristine white kitchen, young and old observed with awe as Hoda Hammoudi meticulously crafted her mujadara hamra.

In Srifa, a village in southern Lebanon, the household’s women gathered for the revered tradition of preparing this dish. In the pristine white kitchen, young and old observed with awe as Hoda Hammoudi meticulously crafted her mujadara hamra.

Every step was carefully documented, for this dish is not merely a meal but a cherished legacy passed down through generations, preserved in its purest form without alteration.

The specialty of Srifa, and indeed of south Lebanon at large, epitomizes the essence of rustic cuisine, with its ingredients sourced exclusively from the area’s fertile land.

Yet, crafting a truly delectable mujadara requires more than just the right ingredients; it demands expertise.

In Srifa, each woman takes pride in achieving the perfect “red” hue in her mujadara, considering it both a badge of honor and an ongoing pursuit.

This deep, rich red echoes the tones of the earth enveloping the village, mirroring the weathered facades of old homes and the tobacco leaves drying in the fields, basking beneath the unyielding sun.

Nabatieh, home of raw meat variety

To say that Zoulfa Badreddine takes pride in her frakeh would be an understatement. “It’s undeniably delicious; it’s my frakeh,” said this Lebanese woman in her 50s, residing in Nabatieh.

To say that Zoulfa Badreddine takes pride in her frakeh would be an understatement. “It’s undeniably delicious; it’s my frakeh,” said this Lebanese woman in her 50s, residing in Nabatieh.

However, it wasn’t amidst the landscapes of southern Lebanon that Badreddine mastered the art of raw meat. Rather, it was in Dakar, Senegal, where her mother, herself born on African soil, imparted to her a skill inherited from her mother. This grandmother, the first from Nabatieh to seek a better future elsewhere, laid the foundation for their family tradition.

Following the Lebanese Civil War, Badreddine’s family concluded their affairs in Africa and returned to their ancestral homeland, bringing their children and elders.

Whereas in Dakar, she had to prepare her kibbeh nayyeh on her own, Badreddine could now count on the invaluable help of her butcher, Hajj Daher. She doesn’t refuse this help when, in the summer, her five grandchildren are entrusted to her care.

When the big house in al-Bayad, the chic district of Nabatieh, is empty, Badreddine, a pleasant woman with an easy smile, is happy to cook. She starts with kammouneh, a fresh and fragrant mixture of cumin, aromatic herbs (basil, marjoram), onion and bulgur.

Kammouneh forms the basis of all the raw meat dishes she loves: Nabatieh’s kibbeh nayyeh (a mixture of raw meat and kammouneh), frakeh (balls of raw meat mixed with kammouneh) and lahmeh madouha (raw meat covered in kammouneh), the names changing according to the amount of kammouneh added to each dish and the final shape of the dish.

In a few months, Badreddine’s youngest daughter will be getting married and moving to Senegal. With her, the kibbeh nayyeh of Nabatieh will surely find its way back to Dakar.

Kibbeh, Zgharta’s pride

“Everyone in Lebanon makes kibbeh. But our kibbeh is something else!” said Angèle Farchakh as she rolled up her sleeves on her balcony overlooking the village of Ehden, where the residents of Zgharta spend their summer holidays. In the cool climate of North Lebanon, Farchakh was ready to showcase her kibbeh expertise.

“Everyone in Lebanon makes kibbeh. But our kibbeh is something else!” said Angèle Farchakh as she rolled up her sleeves on her balcony overlooking the village of Ehden, where the residents of Zgharta spend their summer holidays. In the cool climate of North Lebanon, Farchakh was ready to showcase her kibbeh expertise.

Kibbeh nayyeh (raw), plain kibbeh, plain kibbeh with onion and pine nuts, kibbeh moutabbaka (two layers of kibbeh with a filling of meat, onion and pine nuts), kabkoubeh (Kibbeh dumpling), and the renowned kibbeh arass (large stuffed ball with fat): No variety of kibbeh remains a mystery to this septuagenarian, who has been a mother and grandmother many times over.

“You can’t have a glass of arak without kibbeh nayyeh,” explained Farchakh, who used to prepare it daily for her late husband. “To honor his visitors, it’s time for kibbeh arass,” she continued, her face brightening with a welcoming smile. For feeding the family, nothing beats a dish of kibbeh moutabbaka or plain kibbeh with a small salad on the side. “My daughter lives in Beirut, but she asks for kibbeh at least twice a week,” she added.

With the main theoretical principles covered, Farchakh moved on to the practical work.

She put meat and cracked wheat into the blender. “Kibbeh used to be pounded in a mortar,” recalled Farchakh. She remembers watching her mother at work as a child. The tradition was officially passed on to her when she got married. “I took my first kibbeh exam. I passed with honors,” she quipped.

Fassulia mujadara, a Hammana signature dish

At 9 a.m., Hammana was slowly waking up. The streets came alive and shops opened their doors. In this beautiful village in Mount Lebanon, good humor seems contagious.

At 9 a.m., Hammana was slowly waking up. The streets came alive and shops opened their doors. In this beautiful village in Mount Lebanon, good humor seems contagious.

At the Katanga Cafe, Marie Choueiri took over the stoves. While Hammana might blend tradition and modernity, Choueiri’s kitchen, where she runs the cafe with her husband, stays true to a few timeless dishes. One of these is fassulia (bean) mujadara, also known as fassulia hammaniyeh.

“I’m originally from Akkar [North Lebanon] and my husband is from Hammana,” said Choueiri. “So, my mother-in-law took it upon herself to teach me the bean mujadara — my visa for Hammana!” she joked under her husband’s amused gaze.

“I’ve been living in Hammana for 35 years. I was 20 when I came here. Today, I’ve mastered this dish very well,” she said.

As she chopped the onions, this mother of three shared that her son is coming home in September for a few days’ holiday. “This is the first dish he’ll want to eat,” she said.

The seniora, a sweet combo in Saida

Some pastries are named after their town of origin. One is named after a young maid from Commercy, Madeleine. Others take their names from a cycle race, like the Paris-Brest. Then there are pastries named after their creators, such as the seniora (or siniora, as the name of the famous Lebanese family is usually spelled).

Some pastries are named after their town of origin. One is named after a young maid from Commercy, Madeleine. Others take their names from a cycle race, like the Paris-Brest. Then there are pastries named after their creators, such as the seniora (or siniora, as the name of the famous Lebanese family is usually spelled).

Today, the name Siniora might bring to mind Fouad Siniora, the former Prime Minister of Lebanon. However, around 1859, Siniora was primarily associated with a delightful sweetness, its sugary aroma wafting through Motran Street in Saida, a large town in southern Lebanon.

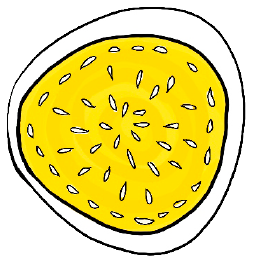

Ironically, the creator of this sweet treat — a yellow, crunchy pastry which, once in the mouth, transforms into a sweet combo — was not originally called Siniora, but Sheikh Ali al-Ghalayini. Sheikh Ali was the son of a beautiful woman, known as ‘Siniora’ (from the Spanish Señora), explained Sami Siniora, brother of Fouad Siniora. Ali al-Ghalayini was soon renamed Ibn al-Siniora (the Siniora’s son). Over time, his name became Ali Siniora, a patronymic taken by the family’s descendants.

Originally, the biscuit wasn’t called the seniora; it was known as the ghraybeh (the foreigner). Sheikh Ali, the great-grandfather of Sami and Fouad Siniora, would offer this pastry to visitors and friends. Over time, the biscuit became known as “Siniora’s biscuit,” which was eventually shortened to the seniora.

“Over the years, the cake became more and more sought-after, and my great-grandfather’s relatives suggested that he open a patisserie and sell the seniora there,” explained Sami Siniora, owner of the patisserie. It was a great success, leading the family to open shops in Beirut, Haifa, Alexandria and Damascus.

Bhamdoun and the Assumption hrisseh

“This dish is a tribute to the Virgin Mary; she is the one who saved us,” said Tony Tabet, 63. Every year since he was a teenager, Tabet has participated in preparing the Assumption hrisseh in Bhamdoun, east of Beirut.

“This dish is a tribute to the Virgin Mary; she is the one who saved us,” said Tony Tabet, 63. Every year since he was a teenager, Tabet has participated in preparing the Assumption hrisseh in Bhamdoun, east of Beirut.

“Two hundred fifty years ago, the Bhamdoun area was ravaged by the plague. Many people died. In Marjayoun, in southern Lebanon, the Blessed Virgin appeared and asked the faithful to take an ancient icon from the church there to Bhamdoun. When the icon arrived in Bhamdoun, the plague disappeared,” said Tabet.

“A few months later, the villagers decided to return the icon to its village of origin. The plague immediately returned, and they had to bring it back. The icon has been in Bhamdoun ever since, and we prepare the hrisseh every Aug. 15 as a thank-you to the Virgin,” continued the 63-year-old.

Hrisseh is a dish that is both simple and time-consuming to prepare. It consists mainly of mutton and wheat, which are brought to a boil in water to create a homogeneous mixture. The cooking process takes four to five hours, especially when preparing the dish for a large gathering, with the meat of dozens of sheep simmering in the pots.

Halawet al-jeben, queen of Tripoli

While Tripoli has long been renowned for its pastries, much of this fame can be attributed to Abdel Rahman Hallab’s Kasr al-Helou, this pastry shop passed down from father to son since 1881.

While Tripoli has long been renowned for its pastries, much of this fame can be attributed to Abdel Rahman Hallab’s Kasr al-Helou, this pastry shop passed down from father to son since 1881.

Among the many specialties of the shop, halewet al-jeben, made with cream and cheese, holds a special place. “Halewet al-jeben is Tripolitan. It loves Tripoli and likes to stay there,” said Zaher Hallab, 32, grandson of Abdel Rahman and head of the company’s production line. Hallab was adamant: Although this sweet is now prepared in Beirut and all over Lebanon, its flavor remains special and authentic only in Tripoli.

The shop’s vast kitchen, spread over several floors, is filled with the delicious smell of freshly baked baklava. Halewet al-jeben, however, has its own department and its chef.

“Tripoli used to be the commercial center of several neighboring regions, stretching as far as Syria. The city was known for its production of dairy products, particularly cheese, as well as semolina and sugar cane,” explained Hallab.

“To avoid losing the surplus of these products, we had to take up the challenge of designing a dish that would contain all three ingredients,” he added.

The result is halewet al-jeben, made with cheese, semolina, sugar and cream (ashta).

Mufataka, Beirut’s traditional and rare dessert

At 6 a.m., the Makari-Hachem patisserie in Basta, a district of Beirut, was already bustling with activity. “The king of mufataka” began to work.

At 6 a.m., the Makari-Hachem patisserie in Basta, a district of Beirut, was already bustling with activity. “The king of mufataka” began to work.

Khaled al-Hachem meticulously weighed the rice, the essential ingredient for mufataka, the quintessential traditional Beirut dessert. This dish, a yellow rice pudding without milk, is popular with the Sunni community in the capital but remains relatively unknown in other areas of Lebanon.

“This dessert made from rice, sugar, turmeric, pine nuts and sesame cream originated in Beirut in 1880,” said Hachem in the small patisserie he has run for over 40 years.

“Sunnis used to make this dessert on the last Wednesday in April to commemorate the Prophet Yaacoub. Now, we cook it every day. It’s an essential food and can be enjoyed both for breakfast and as a dessert,” he explained, stirring his mixture with love and force, explaining the name mufataka which refers to shoulder dislocation.

In the Hachem family, however, the preparation of mufataka is set to end with Khaled, as his sons are not keen to take up pastry-making again and spend hours every day stirring the mixture as it cooks in large pots on a gas burner.

“I was 12 when I started making mufataka with my father and uncle. Today, none of my sons want to do it,” said the pastry chef. “Sadly, I think I’ll be the last to carry on the family tradition.”

This article was originally published in L'Orient-Le Jour and translated by Sahar Ghoussoub.