Traditional brass raqwehs line the counter at Café Younes in Beirut's Badaro neighborhood. 2024. (Credit: Joao Sousa/L'Orient Today)

For most people in Lebanon, the memories are the same: coffee poured into tiny porcelain cups in the mornings and after meals, served amidst sobhiyet (morning gatherings) and accompanied with banter, Fairouz and the latest news. Coffee enjoyed by the household’s elders, served to guests, sipped alone with the paper, at break time, with or without cardamom, with or without sugar.

Dalia Jaffal, chief founder and operator of Kalei, a specialty coffee shop in Beirut, knows the tradition well.

“My earliest memories of coffee are related to my grandma,” she says.

No Lebanese morning is complete without it.

“I remember when we would stay at her place, the first thing she would do in the morning is prepare a raqweh [a traditional coffee pot with a long handle] and have a cigarette with it.”

While traditional Lebanese ahweh, consisting of finely ground, dark roasted beans and prepared in a raqweh, is no longer the only option available to caffeine lovers in the country, coffee remains central to Lebanese social life in ways both old and new.

The ritual and social aspects of coffee seem to follow it through time.

Sitting in Kalei’s “cupping room,” where coffee is tested and baristas trained, Jaffal recalls her teen years, when the only time she got along with her mother seemed to be “first in the morning when we’re having a coffee.”

That’s where her appreciation for the brew really started, she says. “I have good memories attached to it.”

Hidden in an alleyway in the city’s Geitawi neighborhood, Jaffal’s coffee shop inhabits a house that was abandoned in 1984, during the Lebanese Civil War.

Kalei's "cupping room," where flavor profiles are tested, and barista trainings are taught. Beirut, 2024 . (Credit: Joao Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Kalei's "cupping room," where flavor profiles are tested, and barista trainings are taught. Beirut, 2024 . (Credit: Joao Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Kalei originally started as a specialty coffee roastery, where Jaffal would curate blends to be tested and sold to other companies.

Before the cafe, she worked as a consultant and lived abroad, and recalls visits to Lebanon where she would meet friends over coffee, which was often “not very good and overpriced.”

“You know, one day I want to open a cafe,” she found herself telling a friend one day. “Why one day? Let’s do it now,” was the response she received. And so, in 2015 Kalei Coffee Co. was born.

Today, at Kalei’s Geitawi location, visitors are first greeted by a spacious garden, shaded by tall willowy trees. A faint aroma of freshly ground beans lingers in the air. Twenty-to-thirty-something-year-olds busily type away on laptops, sipping cappuccinos, lattes, espressos, and the like. Coffee sourced from Ethiopia, Colombia, Guatemala, Brazil and El Salvador is on serve.

A barista at Kalei crafts a cappuccino. Beirut, 2024. (Credit: Joao Sousa, L'Orient Today)

A barista at Kalei crafts a cappuccino. Beirut, 2024. (Credit: Joao Sousa, L'Orient Today)

“For sure my grandma would not like it [Kalei’s coffee],” Jaffal laughs. “Because it's more acidic and floral. We’re used to earthy smokey, dark roasted coffee [in Lebanon].”

In 2019, a second Kalei branch opened its doors in Ras Beirut, housed in a Lebanese heritage home built in the 1800s.

“Specialty coffee shops like ours are just a drop in the ocean. But it does cater to a specific bubble,” Jaffal says.

“Coffee houses, like Kalei or others, definitely have a social impact,” she reflects. “Yes people come here mostly for coffee, but they also end up gathering, talking, meeting. People become regulars together. They end up making connections and working together.”

It looks like not much has changed.

Rise of the coffee house

The world’s first coffee houses appeared in Damascus and then started popping up throughout the Ottoman Empire, (of which present-day Lebanon was part) rising in popularity in the 16th century.

These early coffee houses were social centers where men would meet, read poetry, play games like backgammon and share news.

Despite the reservations these coffee shops had toward accommodating women, coffee culture flourished in the private sphere, too.

Historians believe coffee made its way to Europe through the Ottoman Empire sometime in the 17th century.

By the mid-17th century, coffee houses had become commonplace in major European cities like Paris, London and Vienna. Once again, beyond leisure, these establishments served as social hubs for intellectual discussion and news exchange.

Coffee culture transformed yet again with the invention of the espresso machine in Italy in the late 19th century, giving rise to various espresso-based drinks like the cappuccino and latte.

The rise of the coffee shop did not come without its share of controversy.

Coffee and power

“Coffee has interesting associations with power,” says Tylor Brand, a Middle East history professor at Trinity College Dublin.

The Ottomans were introduced to coffee through their contact with coffee-rich Yemen (then part of Mamluk Egypt), which they would come to conquer in the 16th century. Soon enough, coffee caught on, spreading like wildfire throughout the vast empire via its trade routes, reaching Lebanon around mid-15th century.

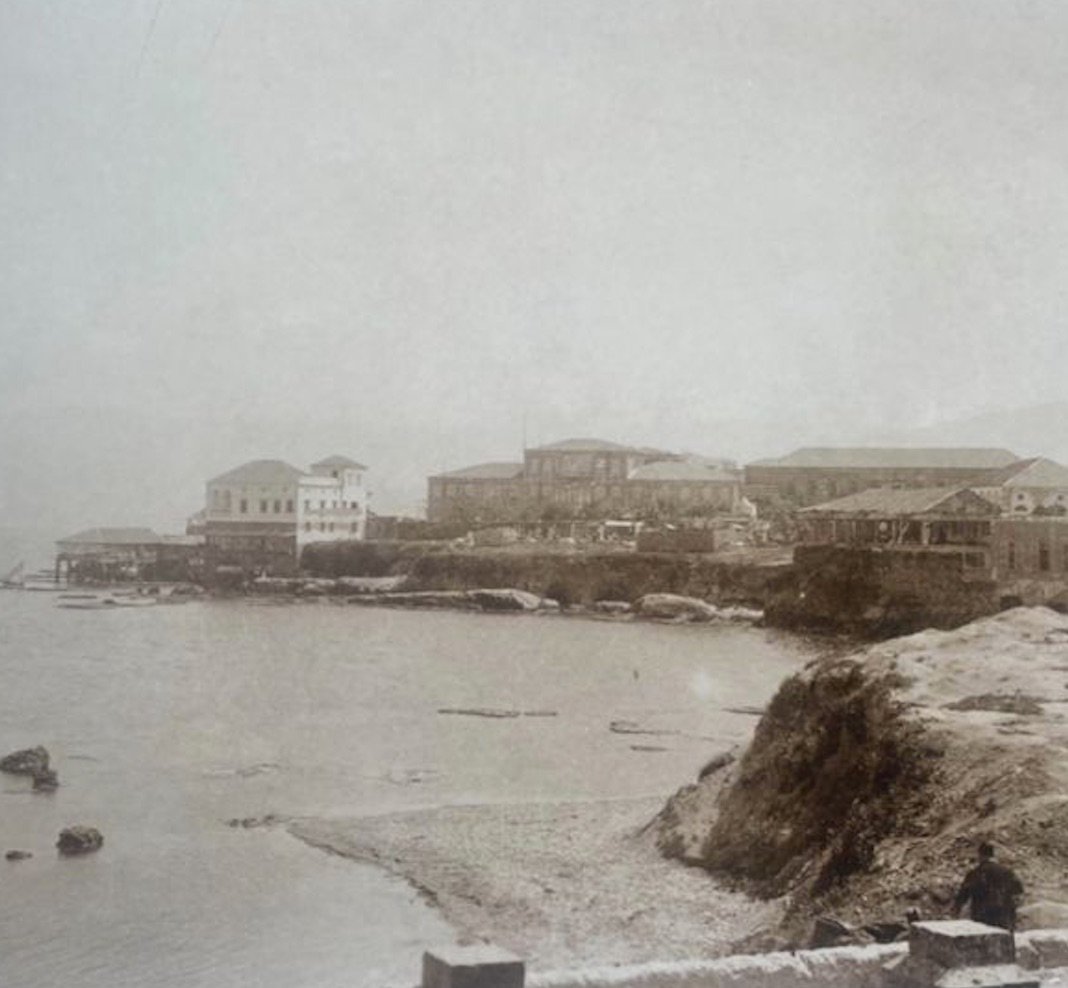

The Hajj Dawud Cafe in Mina al-Hosn . Beirut, 1880. (Credit: Unknown. photo taken by Amanda Haydar at the 'Beirut 1840-1918 Photographs & Maps exhibition at Beit Beirut, Oct. 9, 2023)

The Hajj Dawud Cafe in Mina al-Hosn . Beirut, 1880. (Credit: Unknown. photo taken by Amanda Haydar at the 'Beirut 1840-1918 Photographs & Maps exhibition at Beit Beirut, Oct. 9, 2023)

“People were concerned about it at first because it is very clearly a stimulant. When it first hit the Ottoman Empire, you had to assess if this is religiously permissible for Muslims,” Brand says.

And thus, the beverage experienced on-and-off prohibitions by religious clergy and rulers in the Ottoman Empire and Europe.

In those times, the janissaries, an elite cast of soldiers within the Ottoman system, owned and ran all the coffee shops, explains Brand.

“They were most likely to launch rebellion against the Empire if something went wrong. If you were to monitor sedition you would monitor coffee shops. If you want to shut down sedition you shut down the coffee shops. because that’s where people meet up and negotiate revolution.”

From Ethiopia to your cup

But coffee’s journey started far before then.

Brand says it can be traced to the ancient highlands of Ethiopia, where it “trickled into Yemen, and then made its way into the Ottoman Empire.”

The most popular legend attributes the discovery of coffee to a goat herder named Kaldi

in the 9th century. Kaldi noticed his goats exhibiting unusual energy after consuming berries from a certain tree. Curious, he tried the berries himself and experienced a similar effect. Word spread, and soon, coffee beans were being chewed or brewed in local monasteries to promote alertness during religious ceremonies.

But, of course, coffee consumption has come a long way since then. “Customers usually have no idea of all the steps and hands that touched their coffee before it reached their cup,” Jaffal says.

Before Kalei, Jaffal’s work as an agriculture investment consultant took her to Ethiopia. Last February, she made the trip back to select new beans for her shop in Beirut.

“In Ethiopia, coffee is a ceremony,” she explains. “they have a very special relationship with coffee in that country.”

“Usually, a woman prepares the coffee pot. As it’s boiling she pours for everybody three times. Each pour has a different name.” In the Tigrinya language, the first pour is Awel, the second Kalei, and the third, Baraka, she explains.

“The three servings will be different because they’ve sat on fire for different times,” enthuses Jaffal.

She named her cafe Kalei because it’s “the most balanced brew.”

Ethiopia particularly inspired Jaffal because it was the first place she had contact with farmers. “We still buy from these farmers today.”

From local roasters to ‘fast coffee’ and beyond

Before big factories filled supermarket shelves with packaged coffee for raqwehs, Lebanon relied on small local roasters. Even today, many people prefer to buy their coffee from small traditional neighborhood roasteries that grind it fresh into paper bags and sell it by the ounce.

Café Younes was one such small roaster. Today, it is a popular chain with branches across Lebanon and even the UAE and Egypt.

Amin Younes Jr. took over the roastery, which has been in his family for three generations, back in 1996, leaving behind a career in finance.

He developed the roastery further in 2007 when he opened the first “café” Younes in Hamra.

During Israel’s bombardment of Lebanon in 2006, Younes nearly closed shop. But he pushed through, as his father and grandfather had before him.

“We’re extremely proud of our history,” Amin says.

It all started with his grandfather Amin Sr., who like many other young men of his time emigrated to Brazil in the late 1800’s. After working on a coffee plantation, he returned to Lebanon 20 years later and opened what Amin Jr. says is “the first surviving coffee roaster in Lebanon.”

Souheil Younes (Amin Sr.’s son) took over the business in 1965 and eventually opened two additional roastaries. But the Civil War soon broke out, bringing business to a halt.

“It was a cruel and messy war. It was a street war. We couldn’t stay open. But at the end of the day, coffee is not a luxury; it’s a necessity. And when times are rough, people drink more coffee,” says Amin Jr., who was a child at that time.

In 1975, the downtown roastery was destroyed and ransacked. It took Souheil Younes three years before he mustered up the strength to go and assess the damage.

“The only thing left in the shop was the big coffee roaster because it was bolted to the floor,” Amin Jr. recalls. They disassembled the giant machine and moved it to their village in the Shouf where they would roast for the community throughout the remaining years of the war.

Today, he says, Café Younes still roasts its beans with that very same steel roaster, which has since been relocated to the main café in Hamra.

Customers purchase fresh ground coffee at Café Younes in Hamra. Beirut, 2024. (Credit: Joao Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Customers purchase fresh ground coffee at Café Younes in Hamra. Beirut, 2024. (Credit: Joao Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Alas, however, the youth of today often prefer caramel frappuccinos and lattes over mom’s bitter raqweh, and the market in Lebanon has adapted to globalized modern tastes almost naturally.

Amin recalls when the first Starbucks opened in Lebanon in 2001. “The first store opened in Hamra, next to our roastery.” The irony is for decades, his younger brother was the store manager of this first Starbucks.

“Starbucks introduced Lebanon to a different kind of coffee culture,” Amin Jr. says — though today, many Lebanese are boycotting the brand over alleged pro-Israel sentiment.

Despite the urbanization of everyday life and with it, our coffee rituals, Lebanese coffee culture has retained a thing or two from the past — like treating one’s houseguests and catching up over a fresh, warm brew.

“Coffee is more than a beverage, it’s a culture, really. And it’s important that people celebrate it as such,” says Amin.