An exterior view into the Arab Image Foundation library. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

BEIRUT — The suite of rooms that hosts the Arab Image Foundation seems familiar in a way. The workspaces where the documentation, conservation and digitisation of photos take place, the cool and cold storage for prints, plates, negatives, etc, are an archive’s stock-in-trade. The dedicated library space next door is a slight departure, as is the adjacent auditorium, once it’s finished. Up the spiral staircase, a room has a refrigerator and other kitchen gear. Other spaces await definition, though a few photos hanging on white walls, facing shopfront windows seem distinctly gallery-like.

“We’re not assigning specific roles for those areas,” Rana Nasser Eddin demurs. “Our work is definitely rooted in the collections and whatever research and projects can be generated or extrapolated from them. That’s not to say we’ll start putting up curated exhibitions every three months.”

She smiles. “I think that we can contribute in a different way. Maybe different cultural actors or the neighborhood need something else.”

Archivist Jana Khoury at work on the AIF collection. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Archivist Jana Khoury at work on the AIF collection. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Contemporary artist Akram Zaatari and a few colleagues founded AIF in 1997, and the artist-led initiative has pioneered critical discussion of archival practices in the MENA region. In a country whose most robust cultural institutions are of relatively recent vintage, AIF is a unique hybrid. Its archive — over 500,000 photographs stemming from 310 collections dating from the 1860s through the 1990s and spanning 50 countries — has been amassed through the work of artists and researchers as well as donations.

The foundation’s public profile has not been formed by its space — which for years was a nondescript flat in a residential block — but the artists who, like Zaatari, have deployed (duly credited) images from AIF’s collections in their own work.

AIF director Rana Nasser Eddin and artist Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh, a long-time member of the foundation’s board of directors, want to cultivate the institution’s public face. From its expansive new location they hope it will play a distinctive role on the cultural landscape of the city, and beyond.

Gemmayzeh to Qantari

The port blast of Aug 4, 2020 ruined AIF’s longtime Gemmayzeh location. The team took great pains to secure the collections — weather-proofing the space and acquiring a small solar array to offset the wobbly service of EDL and generator rentiers. Nasser Eddin says AIF has since trebled the original number of panels, to help power its enlarged cool and cold storage facilities.

Nasser Eddin cut her teeth working with Andrée Sfeir-Semler at her Karantina gallery before moving to Beirut Art Center early in Lebanon’s financial crisis — serving with Haig Aivazian as administrative and artistic director respectively. She took the helm at AIF in time for the move west to Aresco, where the library entrance faces that of Metro al-Madina.

The foundation’s collections offer a diverse, sometimes amusing, photo history of Lebanon and the region in the 19th and 20th centuries. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The foundation’s collections offer a diverse, sometimes amusing, photo history of Lebanon and the region in the 19th and 20th centuries. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

“The foundation’s previous space was pretty cramped, and a bit closed off, even between different parts of the archiving process,” she says. “Preservation was at one end, digitization at another. Whoever was doing research or documentation was sort of lost between the two.

“We now have a more open layout that reflects the process. There is a lot of communication that goes into developing strategy.”

Talking in the library

The foundation library was quietly opened to the public in mid-March and, as public programming is still under discussion, it is the fulcrum for public engagement.

“We didn’t think it appropriate to open with a lot of fanfare,” Nasser Eddin says, “but specialized collections on the arts, photography, dance, music, performance, theatre and cinema are rare.” Aside from libraries like the one at Ashkal Alwan, such resources are usually reserved for university students and faculty. And quiet work spaces with free wifi, electricity and coffee can’t be taken for granted in Beirut.

Archivist Jana Khoury at work on the AIF collection. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Archivist Jana Khoury at work on the AIF collection. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

“Our space is available for whoever needs it, in whatever way it’s needed,” she explains. “The Anthropology Society in Lebanon has held talks in the library. We are already sharing the space with other published collections.”

One is that of Dawawine, a café-bookshop-exhibition space launched in 2013 with the aim of making books on cinema, contemporary visual, sound and performing arts available to the public. The other is the critically minded multidisciplinary research and design studio Public Works.

“Public Works didn’t have a place to put their own publications and they wanted them accessible,” Nasser Eddin says. “They no longer had a place to put furniture, so half of the tables that you see in the library are from them as well. We’ve also shared resources with the Cooperative for Cinema Professions,” which operates from the Furn al-Shubbak offices that formerly housed Aflamuna, when it was still called Beirut DC.

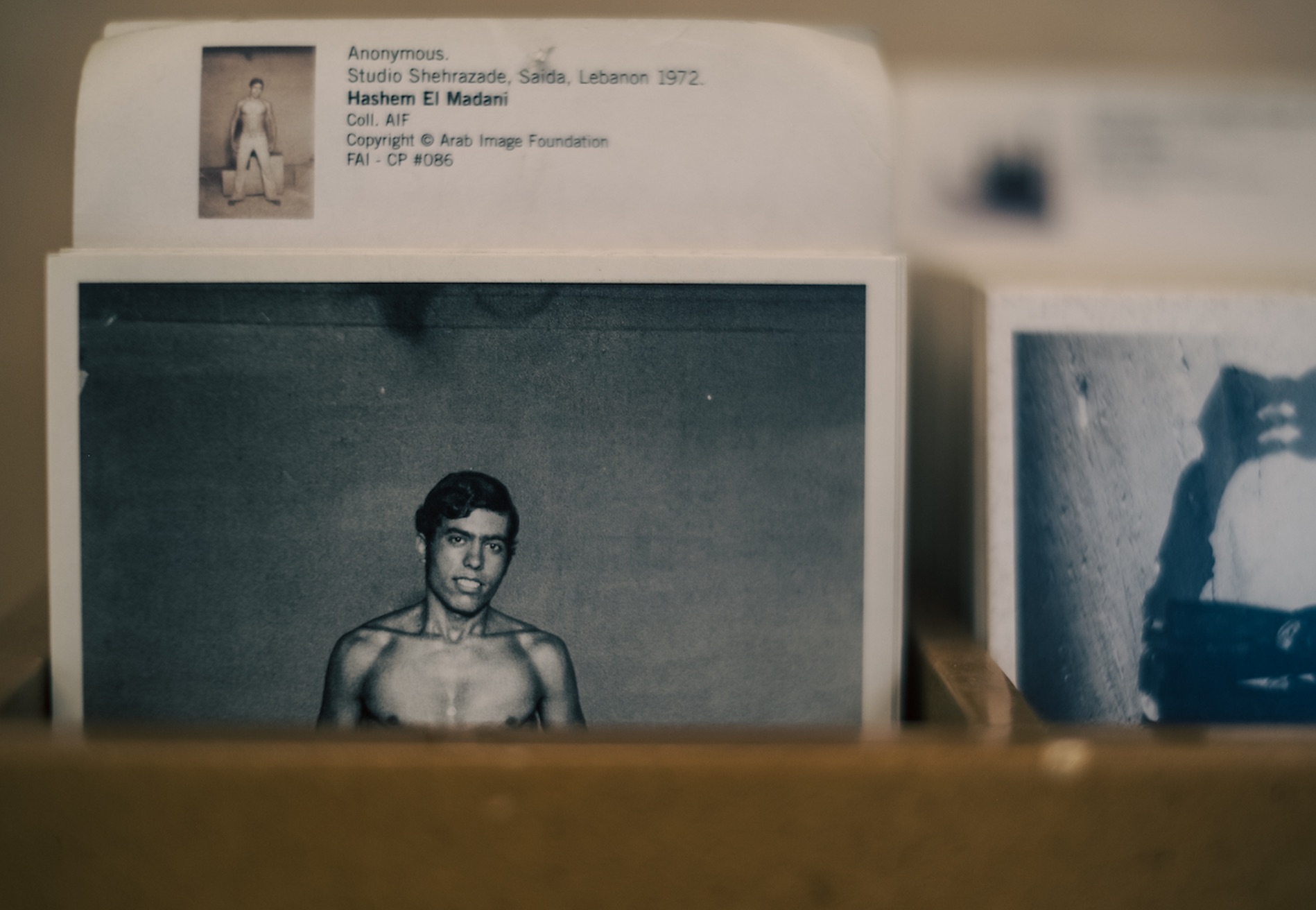

Among the collections is that of Saida studio photographer Hashem Al Madani, whose practice has been sampled in the work of artist and AIF founder Akram Zaatari. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Among the collections is that of Saida studio photographer Hashem Al Madani, whose practice has been sampled in the work of artist and AIF founder Akram Zaatari. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

“They gave us their kitchen,” she smiles, gesturing to the amenities on the far side of the room. “They don’t have a space suitable for projections, so with Dawawine they are building a screening room here at AIF with a DCP projector [Digital Cinema Package, needed to inspect a film’s final cut before distribution].” The object, she added, is to create “an intimate, open, free space for cooperative members to test their films and share with colleagues.”

So far two exhibitions are planned.

“Ashkal Alwan will tentatively stage part of Home Works here in October,” she confided.

AIF is a founding member of the Modern Heritage Observatory (MoHO), a network advocating for the preservation of modern cultural heritage. This year AIF will join MoHO members AMAR (Foundation for Arab Music Archiving and Research), AUB Libraries, Sursock Museum and the Arab Center for Architecture to participate in International Archives Week (June 5-9). The foundation team will give guided tours of the new space on 5-6 June and lead a workshop on conservation of paper archives.

AIF’s plans for public engagement with different cultural institutions, including neighborhood schools and the country’s universities, are ambitiously inclusive.

“Interesting programming — whether it be oriented around film, photography, reading circles or just meeting at the library — is not going to be orchestrated by the foundation alone,” says Eid-Sabbagh. “That’s why we’re creating this bigger framework [for outreach], so people can situate themselves within it, or outside of it. The aim is that a diversity of voices use foundation facilities to express themselves.

“We want to diversify our reach beyond the public that typically attends Beirut arts and cultural events,” she says. “We want people to know they can come sit at the library, plug-in their phones, engage in conversation and get into something they couldn’t encounter otherwise.”

Toward an activist archive

“Our archives have materials that testify to the cruelties and the violence that happened in 1947-48 Palestine,” Eid-Sabbagh reflects. “Less than 100 years later, this violence has accelerated and its documentation is being disseminated in real time. It provokes questions. What does it mean to hold an archive today, if this archive and the way we have dealt with it has not contributed to making genocide impossible?”

Tools of the archival trade at AIF. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Tools of the archival trade at AIF. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Eid-Sabbagh studied history, photography and visual anthropology in Paris, and later received a PhD from the Institute for Art Theory and Cultural Studies at Vienna’s Academy of Fine Arts. Living in Burj al-Shamali Palestinian refugee camp between 2006 and 2011, her research included compiling a digital archive of family and studio photos collected from camp inhabitants. From this research grew her prize-winning collaboration with Rozenn Quéré, the book “Vies possibles et imaginaires” (Possible and Imaginary Lives), facets of which have been reworked into an installation work that has been widely exhibited.

She first encountered AIF during her research in Burj al-Shamali and became a board member in 2008. Eid-Sabbagh continues to work on the Burj al-Shamali material but, like all the board members, she invests a lot of time and energy in the foundation. “I’m interested in AIF not only collecting and safeguarding materials but seeing it do things, thinking critically about how it does things.”

Eid-Sabbagh would like the foundation to take a more activist approach to its collections and is intent on building a research framework for the archive that critically examines questions of social and political solidarity and liberation struggles. It’s a focus that resonates with humans’ current predicament — with political conflict playing out against global economic structures that facilitate the concentration of wealth and power into the hands of a few, pauperises and displaces many and makes the planet increasingly uninhabitable.

“We’d really like to look at our current collections, reread them in order to attain a different understanding of certain moments in history. We’d like to look at different Armenian collections, for instance, and what they tell us about the Armenian genocide. How was it dealt with? How did that affect what is happening today — no one being able to stop the killing, despite the ‘institutional mechanisms’ put in place that say ‘never again.’”

Eid-Sabbagh would like to collaborate with Beirut-born Franco-Egyptian documentary filmmaker Jihan El-Tahri. “As a photographer, she documented Lebanon’s Civil War,” she says. “She has made lots of documentaries on different liberation struggles in Africa and interviewed different PLO fighters in the 80s.

Archivist Rawan Mazeh at work on the AIF collection. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Archivist Rawan Mazeh at work on the AIF collection. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

“I think Tahri’s archive is far too big to be absorbed by a small institution like AIF. We would like to have a conversation with her and accompany the process of inventorying and documenting her archive, and think about how and where it could be housed so that it is more accessible to everyone, rather than sending it to some big American institution.”

While Tahri is still making films, Eid-Sabbagh is interested in how she would narrate her life’s work, an agency that filmmakers and photographers don’t have when their oeuvre is archived posthumously. “We think her rushes [footage edited out of a film’s final cut] are themselves valuable documents that could inform different readings of our collections.”

She pauses.

“I really feel that there needs to be a radical change of how we exist in the world,” Eid-Sabbagh reflects. “I would like different cultural institutions, research institutions and neighborhood associations to engage in this space. To come together and develop conversations that allow us all to better understand the present we’re living in. To develop ways of being in this present that are more generous, that take into consideration the reality of all these different people that live in Beirut, and in the world.”

Happily AIF has backers who are sympathetic with the course adjustment the board has in mind.

“We have been very transparent and clear that one-year project grants are insufficient,” she says. “We are happy to engage in more in-depth conversations, but the foundation requires multi-year grants to create this system. We had to look for funders who are ready for such a conversation, but I think we are doing okay. We have secured certain funding for the next two or three years but we need to work toward a vision for the next five years at least.

“We also need to work on smaller financial contributions, but this will be possible once the space establishes itself as a place where people come, see its benefits and agree to contribute, even $5 a month for example. If enough people do this, then we will have population-based support that comes and uses the space and really benefits from the program and the research we’re doing.”

Eid Sabbagh is not oblivious to the incongruity of her idealism when the prevailing culture — particularly pronounced amid the throes of national collapse and the lurching late-capitalist economy — tends to view solidarity and grassroots change to be facets of a failed model.

“Sharing, thinking in a more common way about collective well-being is not, I think, the natural culture in Lebanon,” she smiles. "It’s all about ‘my career,’ ‘my salary,’ etc. I sometimes think that this violent neoliberal dynamic has penetrated into people here more than elsewhere.

AIF director Rana Nasser Eddin in the foundation’s library, a specialized collection for the general public — plus AC and free wifi. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

AIF director Rana Nasser Eddin in the foundation’s library, a specialized collection for the general public — plus AC and free wifi. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

“Will we be able to achieve our goals? Yes, I believe so. There are lots of people at the foundation who deeply understand these ideas and already embody them in their lives. It’s great to see how far we’ve come so far. There’s still lots to do.”

She laughs quietly. “I tell you, if I listen to myself, I think, ‘Ya rayt!’ [I wish!]. But you must have this aspiration to succeed. It’s a very slow and laborious process but we’ll get there. shway shway.”