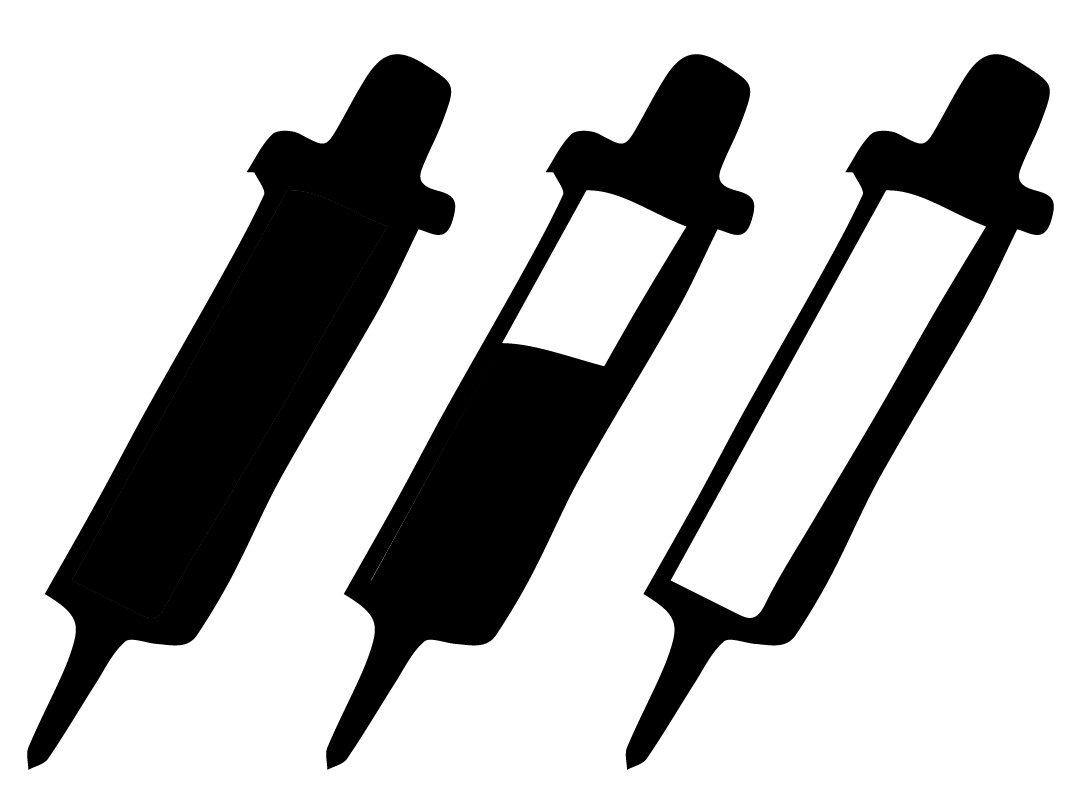

Illustration by Jaimee Haddad.

Illustrations by Jaimee Haddad

JOUNIEH, Lebanon — “Yesterday.” That’s the last time Simon Barakat says a customer walked into his pharmacy on a residential sidestreet in Jounieh asking to buy what he says is the latest weight loss “trend”: Ozempic.

Originally landing on the Lebanese market in 2019 to treat type 2 diabetes, the injectable Ozempic pens are now also wildly popular for quick weight loss, with some users losing 10 or more kilograms in a matter of weeks.

Barakat says the drug is now so popular in Lebanon that “every day I get two or three questions regarding Ozempic.” And that’s only during his working hours at the pharmacy. “Even in the gym, people come up to me, they know I’m a pharmacist: ‘Can you get me Ozempic?’”

“Probably today I’ll get a few requests for Ozempic,” he laughs, in between helping customers.

But amid a recent shortage of the drug from Ozempic’s Lebanese distributor Mersaco, there are precious few legitimately sourced Ozempic injections available on the market.

Of the seven pharmacies L’Orient Today visited one afternoon in February on the outskirts of Beirut, only two said they had Ozempic in stock — and in diminished quantities.

Illustration by Jaimee Haddad.

Illustration by Jaimee Haddad.

And yet, demand is still sky-high, Lebanese pharmacists and nutritionists tell L’Orient Today, feeding an unregulated “black market” for the drug.

To meet that demand — and make extra income — many pharmacists are simply buying Ozempic in foreign countries such as France, Turkey and Egypt and reselling them without prescriptions to people back home in Lebanon hoping to lose weight. One employee at a pharmacy in Metn told an undercover L’Orient Today reporter that they had imported Ozempic informally from France, and that it was available for purchase without a prescription (though they advised speaking with a doctor first).

Sales of counterfeit Ozempic are also on the rise, officials from the Health Ministry and Pharmacists’ Syndicate tell L’Orient Today. It is unclear what the fake versions contain, making them potentially dangerous to consume.

Ozempic has become a “trend,” says Joe Salloum, head of the Lebanese Pharmacists' Syndicate. Sitting in his office at the back of his own pharmacy in Zalqa just outside Beirut, he says he, too, no longer has Ozempic in stock.

According to Nazira Hamadeh, chief regulatory, safety and quality officer at Mersaco, an “increased global demand for Ozempic” and “capacity constraints at some of its manufacturing sites” have caused shortages in some markets, “including Lebanon.”

The drug has been cut off to Salloum, he says, for several months, though customers still ask him “three times per week” about obtaining it.

Do people ever ask him to hook them up with doses from the black market, since he’s head of the Pharmacists’ Syndicate and might have connections?

Salloum says no.

A risky tradeoff?

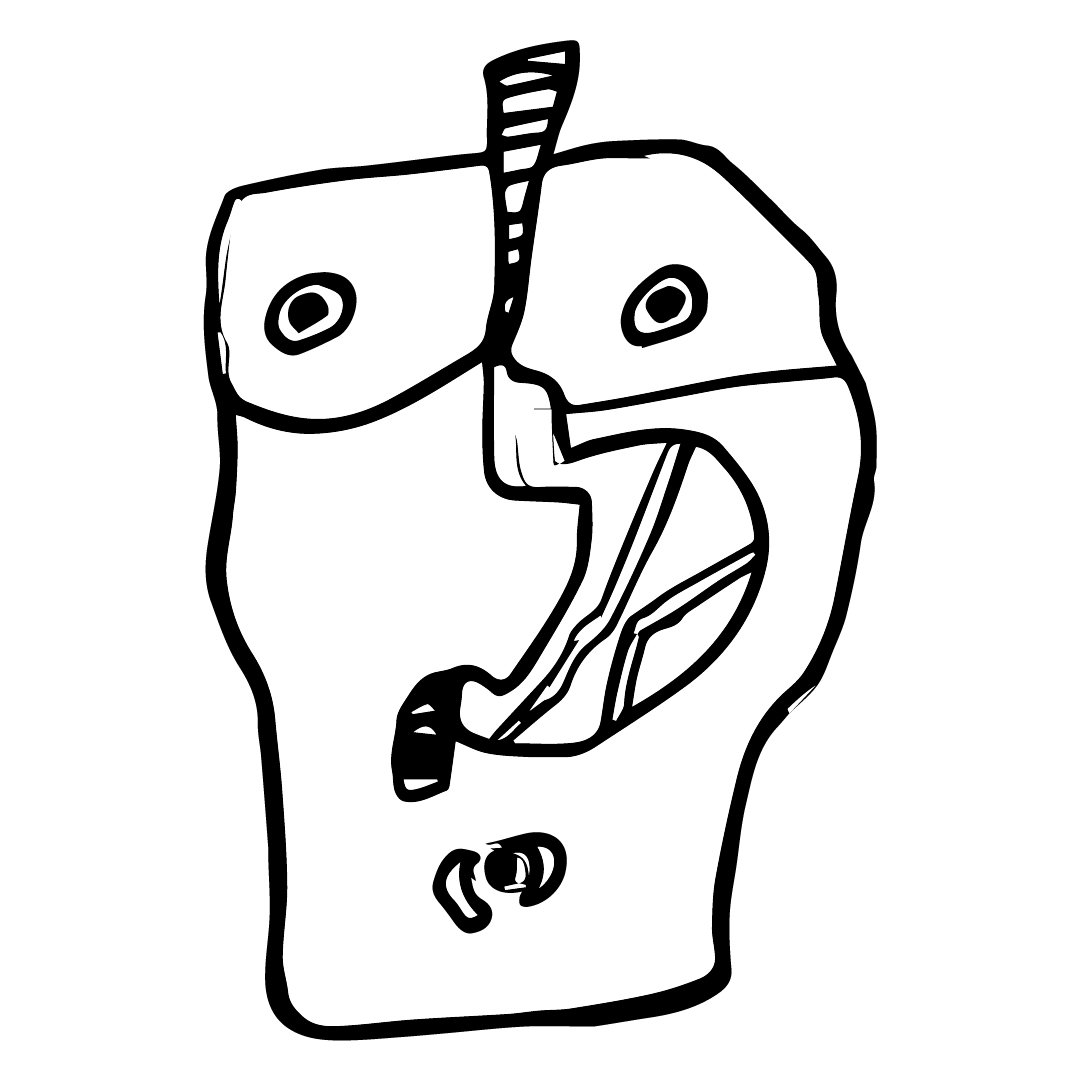

Ozempic is the Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk’s trade name for semaglutide, a once-weekly injectable that works by lowering someone’s appetite and slowing down their digestive system. It can be beneficial for some patients in need of diabetes management or significant weight loss, nutritionists and users tell L’Orient Today.

Illustration by Jaimee Haddad.

Illustration by Jaimee Haddad.

George*, one Ozempic user, says he first obtained the drug only after getting a prescription and consulting with an endocrinologist following years of struggling with his weight and body image. He now obtains his doses through his local pharmacist, who sources it on the black market because of the local shortage, George says. “I never got it ‘legally.’”

An oral, pill version of semaglutide is also now available on the Lebanese market under the trade name Rybelsus, though only in very limited quantities, says Samira Nasreddine, a pharmacist and pharmaceutical representative in Beirut.

She would know — 23-year-old Nasreddine says she herself took Ozempic last year after gaining weight while studying for her final exams. She’s also looking into Rybelsus.

She got her Ozempic “for free” through pharmacist friends, without a prescription, though she doesn’t recommend others do so.

“I’ve been doing diets for years. And years,” she says. As a child, Nasreddine says she struggled with obesity, weighing in at more than 100kg (200lbs) when she reached her teenage years. “I love fashion. I looked at my friends — usually, they dressed in things that were very nice, very trendy. I didn’t have this opportunity … I couldn’t find [clothes] in my size.”

Illustration by Jaimee Haddad.

Illustration by Jaimee Haddad.

“So really why I took Ozempic is because it’s the shortest way, it’s the shortest track for me reaching my goal. I don’t want to struggle anymore.”

Nasreddine says she ended up taking Ozempic for six months, starting out with a 0.25mg weekly dose and moving up to a stronger 1mg. However, the 1mg caused her to “pass out” due to hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), so she decreased her weekly dosage.

According to nutritionists Stephanie Baddour and Romy Moujaes, Ozempic can cause dangerous potential side effects, on top of most patients simply gaining back the weight they’ve lost once they stop taking the injections.

Baddour and Moujaes co-founded Dietetics Institute for Continuous Education (DICE) in 2019 — the same year Ozempic reportedly reached the Lebanese market — and use their shared Instagram account to dispel “myths” about diet culture. Among those myths is that Ozempic is risk-free. Instead, the drug can cause severe nausea, hypotension and even potential thyroid cancer in patients already at risk for the disease, according to Baddour and Moujaes.

“So imagine a person not doing a blood test, not knowing if they have anything” before starting Ozempic, Baddour says.

“And not having the proper follow-up,” Moujaes chimes in. “People are so desperate that whatever is going to help them reach their goals with minimum effort, they want to try it. So sometimes they will forget blood work, blood tests, asking a doctor.”

Illustration by Jaimee Haddad.

Illustration by Jaimee Haddad.

And that’s if the Ozempic they take is safe. Experts warn that black market and counterfeit Ozempic come with extra dangers.

Most recently, in January, security forces shuttered a pharmacy after Pharmacists’ Syndicate inspectors found counterfeit Ozempic in stock, according to syndicate president Joe Salloum. He says the syndicate regularly sends its members to inspect pharmacies.

He declined to provide further details of the January incident, such as the location of the pharmacy or amounts of the seized materials, as documents about such cases are kept “secret.”

It hasn’t been the only such case in recent months.

In 2023, Lebanese authorities found 11 cases of “suspected counterfeit Ozempic,” Rita Karam, director of the Health Ministry’s Quality Assurance of Pharmaceutical Products Program, tells L’Orient Today. “All reported instances were associated with hypoglycemia, with one case necessitating an emergency room visit due to severe hypoglycemia.”

That marks a significant increase, she adds, from the zero cases in 2022.

“With counterfeit medication, we don’t know what’s inside,” says Salloum. And Ozempic brought in illegally from abroad runs the risk of improper transportation conditions, as it’s meant to be kept refrigerated or inside an ice pack.

“The illegal Ozempic market is very dangerous.”

Nasreddine says she isn’t worried, explaining that the more serious side effects are rare. She’s now saving up several hundred dollars to buy another round of Ozempic injections ahead of her engagement party this summer. What about before her wedding? “I hope,” she says. “I hope.”

Illustration by Jaimee Haddad.

Illustration by Jaimee Haddad.

Baddour and Moujaes say such stories are common.

“It’s a trend effect. It’s such a small country,” says Moujaes. As the two women speak with L’Orient Today in a mall cafe near Beirut, a man at the next table perks up at the mention of Ozempic. “Are you suppliers?” he asks, explaining he’s hoping to find doses of the drug.

‘I could easily sell it’

Back in Jounieh, pharmacist Simon Barakat says most customers who come to him asking for Ozempic aren’t looking “for lifestyle management at all, just for a quick weight loss.”

His most recent inquiry came from a man in his early 60s with high blood sugar. “He has many comorbidities. He’s not willing to have a lifestyle management, he’s not willing to give up eating sweets and fried foods and drinking alcohol.” Barakat says he simply taught the customer how to perform the injections should he find Ozempic at another pharmacy, instead of selling boxes of the drug imported informally from abroad.

Are they walking in with doctors’ prescriptions, or simply asking for the injections straight up? “Straight up, of course. It’s a jungle.”

“My sister lives in Paris. And I know doctors in Germany, relatives. I can call them, get a European prescription for Ozempic, have my sister come here with 10 Ozempic in her luggage. I can sell them in 24 hours and make on each $50. I can make $1,000 profit in a matter of one hour. Do I do that? No.”

“This is why I remain poor.”

Instead, Barakat says he sometimes refers customers next door, to the “diet coffee shop” run by his wife Lea, who is a nutritionist. There, Lea and her toddler-age daughter sit with friends one sunny morning with coffee and gluten-free chocolate chip madeleine cookies. Every Monday the coffee shop also becomes Lea’s clinic for consultations with her 12 clients, who come to her for diet plans.

One of her friends, Maria*, who is hanging out in the cafe with her young son, smiles and laughs at the mention of the drug: Maria’s husband, a doctor currently working in Saudi Arabia, recently took Ozempic for weight loss, and prescribed it to himself. Her aunt also took Ozempic for weight loss, Maria adds.

But Lea says she is skeptical of that route in most weight loss cases.

In the meantime, she says she’s simply cooking balanced meals for her family, in the hopes that her own daughter will grow up enjoying healthy food without restrictions.

“I will teach her to be confident and love her body.”

*Names have been changed at the interviewees’ request, to protect their privacy.