A student sits for Turkish language lessons in Aidamoun, another Akkar village with significant Turkmen presence. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

KUECHRA, Akkar — Down a narrow mountain road in northern Lebanon’s Akkar governorate is a tiny village with Turkish emblems speckled throughout: on signposts and store signs, plaques on the mosque and public schools, and noticeably, in the form of a monument crowned with the Lebanese and Turkish flags.

It doesn’t stop there. In local homes and shops, residents still speak the Turkish language, albeit in shrinking numbers.

Kuechra, home to just 2,800 people, has the distinction of being one of Lebanon’s few Turkish-speaking villages, a holdover from four centuries of Ottoman rule.

Specifically, this rule lasted from the early 1500s to the end of WW1 in 1918, and echoes in Lebanon’s contemporary cuisine, customs and even legal codes.

Centered in Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire spanned three continents at its peak. Unlike imperial France and Britain however, the Turks did not insist on transferring language to their subjects.

The Turkish and Lebanese flags side by side, on top of a monument at the village's entrance. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

The Turkish and Lebanese flags side by side, on top of a monument at the village's entrance. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

But in Kuechra, there are hints of what Lebanon could have looked (and sounded) like if it had inherited the Turkish language.

“Kuechra was founded about 420 years ago,” mayor Muhammad Karim tells L’Orient Today.

According to local legend, “there was a conflict between Beit (house of) Merheb and Beit Jaafar,” feudal Lebanese Ottoman chieftains, “so Turkey sent mura2abin [intelligence officers] to see who was impinging on whom,” Karim explains.

“These mura2abin likely founded Kuechra and they eventually became Lebanese when the Ottoman Empire fell.”

But even then, no one knows for sure how this Turkish community formed. “It’s not written,” Karim says.

Some historians believe Lebanon’s Turkish villages could have stemmed from the Ottoman Army’s logistic bases in the region, possibly established during the time of Sultan Selim I’s campaign to Egypt in the 1500s.

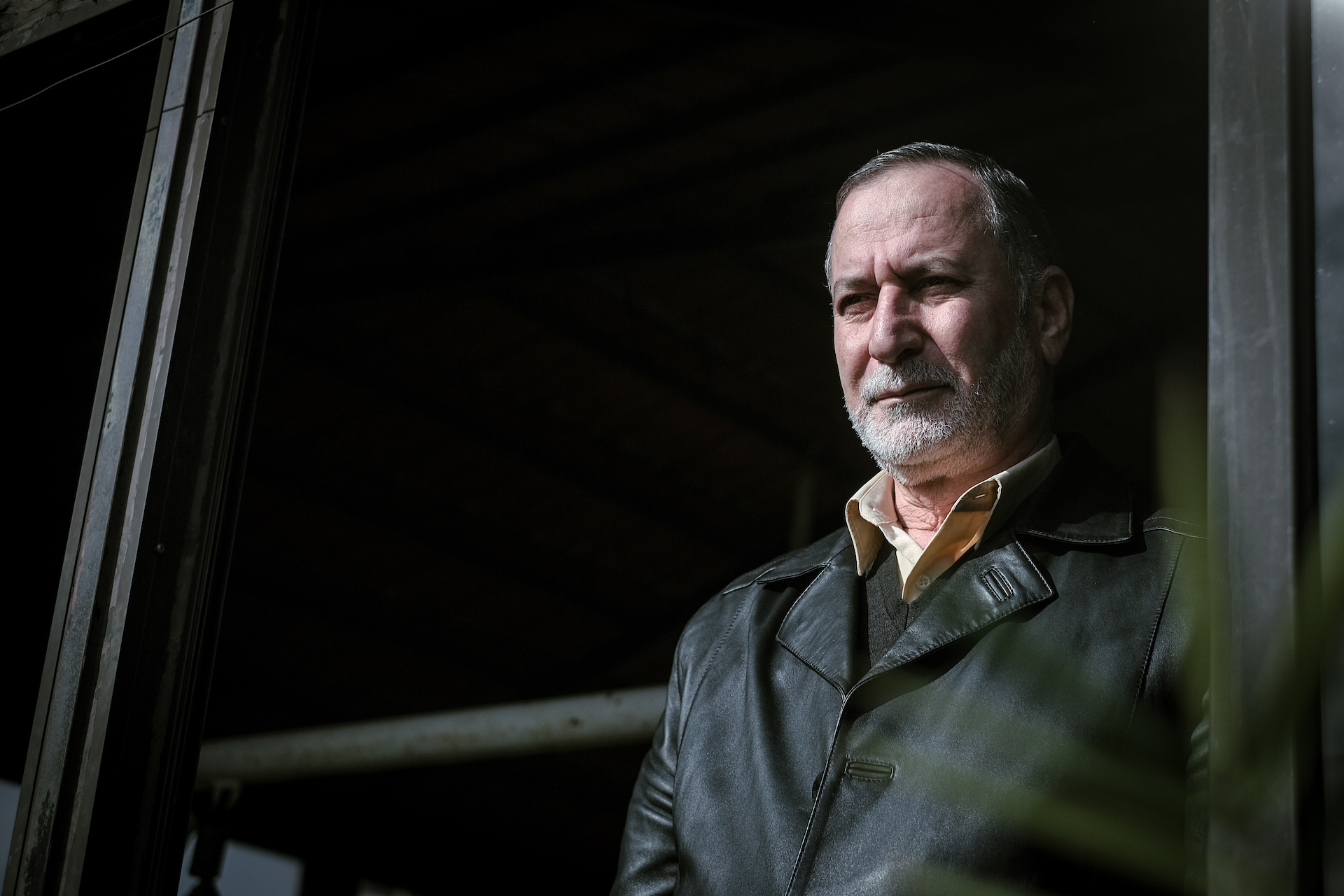

Kuechra mayor Muhammad Karim in December 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Kuechra mayor Muhammad Karim in December 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Aside from the Turkish language remaining as a sort of vestigial tail of Kuechra’s Ottoman past, residents say they are culturally Lebanese.

“Our traditions and customs are Lebanese. Turkish and Lebanese customs are similar anyway,” Karim says.

A couple of generations ago, that was perhaps a different story, he says. Everyone spoke Turkish and “exogenous marriage” was heavily frowned upon.

“The elderly in Kuechra find it difficult to speak Arabic,” according to Karim’s 32-year-old daughter Gulay.

“They still mess up the grammar and refer to ‘him’ as ‘her’ and ‘her’ ‘him.’ These days, the kids understand [Turkish] but don’t really speak it much because they don't practice enough,” Gulay says. Her name is Turkish in origin, and she herself speaks fluent Turkish.

For other young people, things have opened up in recent decades. Now they “give and take [marry] from outside,” her father, Karim, says.

A street sign in Kuechra with Arabic, Turkish and French writing. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

A street sign in Kuechra with Arabic, Turkish and French writing. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

An uncanny bond

In 1989, Karim was a young engineer serving in the Lebanese Army.

“There was an Army protocol [event] one day,” Gulay recounts, based on family lore.

“My father and his cousin were there and the Turkish consul was passing by. He noticed my father and uncle speaking Ottoman Turkish and just about flipped out. He was like ‘Don't move! I’m coming back,’ and went off and called the Turkish Ambassador Ibrahim Dicleli over to meet them.”

“The ambassador was in disbelief. He was in tears and told them to come sit with him. It was 1989 and Turkish relations with Lebanon were strained back then because Syria still held sway over Lebanon,” she says.

The Turkish ambassador reportedly visited Kuechra shortly after.

Food from a shop in Kuechra. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Food from a shop in Kuechra. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

“They found their long-lost brethren. It's a protocol now. All Turkish Ambassadors visit Kuechra and Aidamoun,” she says, another Turkish-speaking village in Akkar.

Today, Turkey has strong connections with Lebanon’s Turkish-speaking villages and provides them with development aid, Kuechra being the most homogenous population of Turkish speakers. They helped Kuechra renovate and build their schools, a mosque and a solar-powered water pump.

Preserving linguistic tradition

Gulay recently moved to Stuttgart, Germany where she works with a Turkish-German cable company. She studied international relations and diplomacy at Ankara University, an opportunity helped by the fact that she spoke Turkish. “Growing up, we spoke Turkish at home and watched Turkish television,” she says.

Lebanon’s Turkmen have been learning the language informally, at home, since the Ottoman Empire’s reign came to an end. "That's why in 2010, we requested a language teacher,” Gulay explains.

A shepherd guides his flock near Kuechra. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

A shepherd guides his flock near Kuechra. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

“They [Turks in Turkey] understand us. But their grammar and vocabulary is modern; it's different than the old version spoken in Kuechra. Ottoman Turkish was different than modern Turkish.”

“Language is the main thing that keeps people connected to their culture, roots and traditions. If the language is gone it's all gone,” she says.

These days, parents are speaking less Turkish to their children, so that it “doesn’t negatively affect them in school,” says mayor Karim.

“It’s like registering a foreign person in an Arabic school,” he says, recalling how Turkish-speaking students struggled in the Lebanese school system a generation or two ago.

Kuechra’s public high school principal, Khaled Abdul Ghani Ismael, was among those who struggled with the language difference when he was younger. He recalls not knowing any Arabic when he started school as a kid and being made fun of for it.

A sabil fountain installed by the Turkish government in Kuechra in 2009. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

A sabil fountain installed by the Turkish government in Kuechra in 2009. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Turkey’s Culture Ministry now sends a Turkish language teacher to improve and preserve the language in Kuechra.

The village’s current Turkish language instructor is Ömer Kurtoglu, who gives after-school lessons to the community at the public school.

“In Lebanon, they speak Ottoman Turkish… Kuechra Turkish is more similar to Azeri Turkish [Azerbaijani, a Turkic language]. They still use Arabic script,” Kurtoglu says.

Turkey's post-war administration replaced its use of the Arabic alphabet with the Latin alphabet in 1928, after the Ottoman Caliphate was dissolved and the modern Republic of Turkey was declared under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk five years later.

Kurtoglu currently teaches four times a week, to three different age groups, and is on a one-year renewable contract.

Still, his Turkish lessons are given outside of the school’s official curriculum. School principal Ismael appealed to the Education Ministry on several occasions to add Turkish to the languages that can be taught in Lebanese schools, but with no luck so far.

A flock of sheep near Kuechra. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

A flock of sheep near Kuechra. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

For now, Katralou says “the village elderly speak Turkish best. Especially the women.”

“They use some old words that have changed in the modern dialect on the mainland. But it's comprehensible. Most young kids don’t speak it,” Kurtoglu remarks.

“It was customary for brides to have a henna night. In Turkey, they still do this. And in Kuechra they used to do this. But now it's receding, even in Turkey with modernization. Turkey used to be more rural, now it's all becoming urbanized.”

Circumcision was also a huge milestone. “They’d do parties for it and celebrate. They used to celebrate circumcisions in Kuechra too, but this has nearly disappeared.”

Meanwhile, Gulay says she is passing down the Turkish language to her son, with whom she speaks both Turkish and Arabic.

“In many ways, women are the main representatives and carriers of culture. And they are responsible for passing it on to the children,” she says.

“It's in our amaneh [gaurdianship]. It’s in our hands.”

Correction: This article has been updated from its previous version to correctly spell the names of Ibrahim Dicleli and Ömer Kurtoglu.

A view of the mountains in rural Akkar governorate, near Kuechra. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

A view of the mountains in rural Akkar governorate, near Kuechra. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)