A rental sign in Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today/File photo)

BEIRUT — Days before a deadline to ratify a new rent law for commercial properties, controversy remains over measures that would allow landlords take back their properties from tenants and dramatically increase rent for the first time in decades.

Tenants decry the upcoming changes while property owners argue the old, frozen rental agreements — which lost most of their value due to Lebanon’s economic crisis — stifle much-needed income.

The law has yet to go into force.

Passed by Parliament in its last session in December, the new law should have been transferred to the president. But since Lebanon has had no president since Nov. 1, 2022, the law was transferred to cabinet instead, who refrained from publishing it in the Official Gazette during its session on Dec. 19.

It is unclear whether cabinet, on whom the constitution imposes a one-month deadline for publishing such laws, will move forward with it or send it back to Parliament for amendments — a move lawyers and experts say cabinet has no jurisdiction to take.

Cabinet is scheduled to hold a session on Friday and on its agenda is re-examining its decision related to this law.

Once minted in the Official Gazette, the new law will affect around 24,900 tenants renting properties under the old rent law, according to Ministry of Finance statistics.

What are the amendments to the old law?

In its latest legislative session on Dec. 14 and 15, Parliament passed a series of amendments to Lebanon’s old rent law.

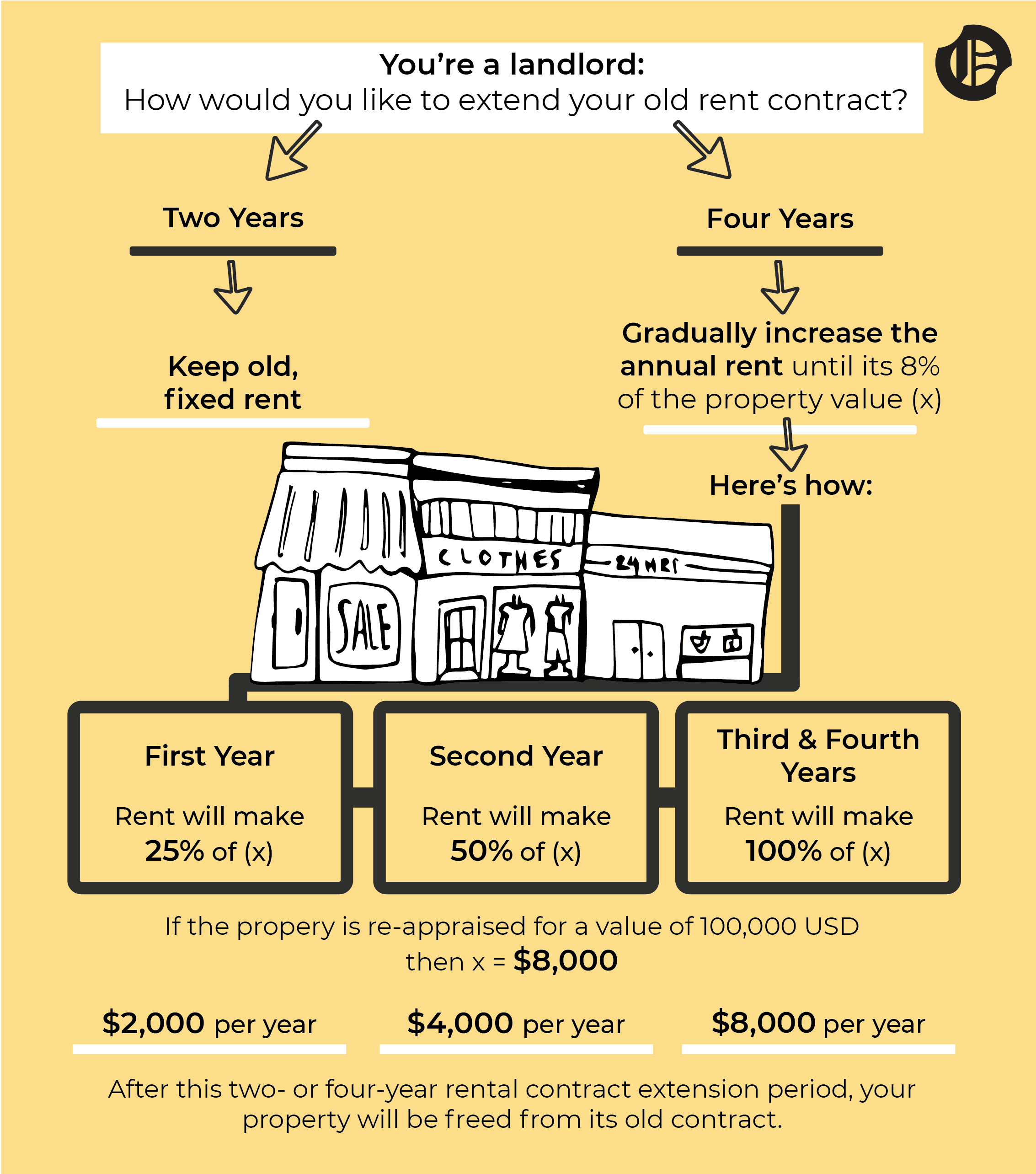

The adjustments could see commercial properties freed from constraints legislated in 1963 by either extending the existing leases for four years alongside steep rent increases, or extending them for just two years with no rent hikes.

Tenants who rented their business before 1992 have been paying rent far below market price for decades, thanks to the old 1963 law that made it possible to freeze rents and to the devaluation of the Lebanese lira in the 1980s and in 2019.

That law no longer applied to rent contracts drawn up in 1992 onward.

A shop in Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today/File photo)

A shop in Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today/File photo)

The new law is aimed at changing that. Here’s how it works:

If the owner chooses to free their property from the old rent law in two years, the tenant is required to pay the same rent fee during these two years.

If the owner chooses to keep the tenant for four years before freeing their property from the old rent law, the property will be subject to a gradual rent increase. The commercial property will be re-appraised based on its location and other factors, by experts hired by legal courts — and eight percent of that appraisal value will become the annual rental fee owed by tenants.

Of this eight percent, 25 percent will be paid by the tenant during the first year after the new law becomes effective. Fifty percent of it is paid for in the second year and 100 percent for the third and fourth years.

To put this into perspective, if the value of a property is estimated at $100,000, the rent fee per year according to the new law becomes $8,000.

For the first year, the tenant pays $2,000. For the second year, the tenant pays $4,000. For the third and fourth years, the tenant pays the full $8,000.

After the extension period of two or four years, landlords are free to re-lease, sell or otherwise use their properties as they wish.

(Credit: Nima Salha and Jaimee Lee Haddad)

(Credit: Nima Salha and Jaimee Lee Haddad)

Meanwhile, the new amendments also exempt owners of 90 percent of their property taxes, tariffs and fines for the previous 10 years, ensuring that they don’t have to cover for fees not paid by the tenants — but also exempting them from paying most of their own unpaid dues.

Tenants argue that the new rent is too dramatic — and unaffordable — of an increase.

Among them is Bassam Mkhaiber, who attended a tenants’ rights protest in Beirut on Tuesday.

He has rented a shop in Beirut since 1958 and currently pays LL5 million in annual rent, around $55.

“We are with rent increases but not eight percent,” he added. “We want to find a solution that would work for us and the owner.”

However, owners claim that some tenants — including those owning profitable businesses such as gold shops and health clinics — would be able to pay the new fee. It would also, they argue, be a much-needed income boost amid Lebanon’s years-long economic crisis.

Why are tenants against the law?

Tenants say owners taking back their properties, whether in two or four years, is unfair to them. Most of them had paid an upfront fee, called “vacancy fee,” at the start of their lease, as part of an informal deal to the owners, in addition to the yearly rent fee.

The vacancy fee amounted to around 15 to 20 percent of the property’s value.

A shop in Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today/File photo)

A shop in Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today/File photo)

Mkhaiber told L’Orient Today he paid LL275,000 as a vacancy fee in 1958. This used to be equivalent to around $87,000 at that time’s LL3.16-to-the-dollar exchange rate.

“Let [the owner] give me back the vacancy fee I had paid and I will vacate,” he said. “Because two years to vacate [the property] with no money will be a humiliation.”

Another issue lies in the fact that tenants will struggle to find an alternative, especially with the economic and bank collapse in Lebanon.

Pharmacists in particular face a conundrum should property owners end their leases.

Their licenses restrict them to establishing pharmacies within a specific 300-meter area of their municipality, Joe Salloum, head of the pharmacists syndicate, told L’Orient Today.

“If a pharmacist was forced to vacate his property, they might not be able to open another pharmacy in the same neighborhood,” he added.

On top of that, “if the pharmacist wishes to transfer their license from one place to another, they are required to obtain a financial clearance and a security clearance,” Salloum added. “These processes might take a year or more… [posing] another obstacle.”

The other side of the story

“The tenant is selling and trading his merchandise in fresh dollars, yet pays rent at the old lira rate,” Patrick Rizkallah, President of the Rented Buildings Owners Syndicate, told L’Orient Today.

“This is a form of injustice and it is 50 years old,” he lamented, in reference to the 1963 law.

A shop in Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today/File photo)

A shop in Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today/File photo)

Rizkallah scoffed at the thought that eight percent of the property’s value as a rent fee is high.

Among those who still rent commercial spaces under the old law are doctors, he argued.

“They charge hundreds of dollars from patients for their sessions, yet pay rent in lira… this is a joke!”

He accused tenants of being “greedy,” and said his group demands cabinet to publish the new law amendments “immediately.”

One lawyer who specializes in rent cases said he owns several commercial properties. He spoke on condition of anonymity to protect his legal practice.

He said that he has been receiving rent fees amounting to LL600,000 and LL700,000 per year from his tenants — today equal to about $7-$8.

“Tenants go to the notary, pay around LL2 million in fees [more than twice the rent] to deposit the rent so that I go and pick it up,” the lawyer said.

“Enough is enough,” he said. “They pay $10 for renting my properties and then want me to pick it up from the notary… I don’t want that rent.”

“This is exploitation,” he said. “The landlord should have the right to invest in his property without having a rent extension law be imposed on him.”

Authorities have been extending old rents for decades.

Moreover, under the old rent law, some tenants have become rentiers themselves by subletting the property to other tenants, though this is an illegal practice.

“[Tenants] are exploiting the situation and are trading people's properties! Imagine that you are an office owner and the tenant is subletting it without your permission,” Rizkallah, the Rented Buildings Owners Syndicate president, said.

Lia Nurpetlian inherited, along with her brother and sister, a building in Burj Hammoud from her deceased parents. It consists of three apartments and two shops and was built by her grandfather.

“The weird thing is that a man has been renting a shop since my father's time and once he died, the property was automatically passed down to his children, and you can't do anything about it.”

She said she tried to liberate the properties from the old rent contract several times through lawyers, which ended up costing her “more than the rent.”

“Then, I stopped, because I was really tired,” she said.

“One of the tenants wasn't even running the shop. So I hired another lawyer and took photos [for evidence]... but once the guy found out, he started opening the shop again,” she said.

One of the shops sells children’s clothing. “They sell their merchandise in dollars but pay LL2 million a year in rent,” about $21 at today’s market exchange rate, she added.

Now, she waits “for the guys to die, which is horrible to say, so that I can take the shop.”

She said tenants can only pass down the property to the second generation only but not third.

Nurpetlian said she wants the shops back so that she can help her brother, who is a recovering addict, find a job.

“I want to open, for example, a bakery for him, where he can feel like he's giving back to society. I feel like it's fair because it's our land, our building.”

“Burj Hammoud has a lot of potential. The problem is that most of the shops sell outdated brands and run old businesses… It's the same faces I've been seeing since I was five,” she added.

Nail in the coffin for small businesses?

Mona Fawaz, co-founder of the Beirut Urban Lab at the American University of Beirut, agreed that the old rent law is “outdated” and that “there is no doubt that some landlords are not receiving the proper rent.”

However, she argued several issues need to be tackled before enforcing the new changes.

“What is the data that supports the new law? Did we do a survey of all the businesses and figure out that 80 percent of the tenants are making a lot of money and not paying the rent? Or is it 10 percent, and we're gonna close the only source of income for maybe… thousands of families who would otherwise go hungry? We don't know, we really don't know,” she said.

Fawaz told L’Orient Today there had been no such survey conducted before passing the new law amendments.

MP Imad al-Hout, who was involved in devising the new law amendments for the old rentals and has been lobbying for their enactment, told L’Orient Today that parliamentary committees conducted studies and took note of different points of view before writing the law. He did not give details on the findings of the research.

Downtown Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today/File photo)

Downtown Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today/File photo)

“Who decides on the value [of the property]? How do we know this is the fair value? How many of the stores will close? What is the government's strategy to support small-scale businesses?” Fawaz asked.

“To propose a law like this without figures or data, without prediction for some small businesses that may die at the time when our national economy is almost nonexistent, we are potentially killing some vital economies and some vital sources of livelihood,” she added.

“We cannot even say if the law is good or fair in the absolute [sense] in the absence of any scientific data” that would paint a clearer picture of the situation.

Fawaz said the government could start with the cases of tenants subletting their shops, for example.

“That would actually reduce the lawsuits, as there are currently many lawsuits against people subletting and renting out the properties without having the right to do so,” she added.

Still, big unanswered questions remain for the fate of tenants who rely on their small businesses.

For one, Mkhaiber, the longtime shop tenant in Beirut, said he doesn’t know if he might be able to continue running the business he’s had for decades should the new law be put in place.

“This law is exclusively giving the owner the right to terminate a business that has been there for over 40 years,” he said.

Fawaz also pointed out that property owners might not even be able to rent out their properties at the market price once the space is freed from the old rent, “because there is no economy” for potential tenants to afford the new prices.

Instead, landlords could simply resort to selling the properties to developers who will demolish the building and build a new establishment, she said, adding that, nonetheless, there aren’t that many developers left in Lebanon.