'Falasteen Horrah' (Free Palestine), an illustration by Raphaëlle Macaron utilizing plants native to Palestine. (Courtesy of the artist)

Just days before its scheduled sale on Thursday, Nov. 9 in London, Christie’s removed two artworks by the Lebanese artist Ayman Baalbaki from its catalog, sparking outrage among collectors and art industry professionals in the region.

The first piece, Al-Moultham (the veiled one), a large acrylic on canvas (measuring 200 x 150 cm) dating back to 2012, portrays a man whose face is concealed with a keffiyeh. The second painting features a man wearing a gas mask with a red headband on his forehead, bearing the word “thaeroun” (rebels) written in Arabic.

Although this scandal gained significant attention, likely owing to the prominence of the English auction house, it reflects a wider trend in the worlds of art and fashion. These industries are currently grappling with seismic shocks amid a tumultuous, and often racist witch-hunt, targeting (mostly Arab) figures expressing solidarity with the Palestinian cause, and at times, even less than that.

Merely expressing disapproval of Israel's crimes against humanity and violations of international law have led to immediate accusations of anti-Semitism in certain circles.

Those who have spoken against Israel find themselves subjected to harassment, insults, cancellations, and sometimes lose their jobs for reasons that remain unclear.

An illustrative case is that of Samira Nasr, editor-in-chief of Harper's Bazaar. Nasr faced intense backlash after sharing on Instagram that Israel’s cutting Gaza's electricity and water was “the most inhumane thing” she has seen in her life.

The violent reactions prompted Nasr to issue a public apology. According to the New York Post, Nasr is now "fighting to keep her job."

Artforum editor David Velasco and eLife editor Michael Eisen had even worse experiences: they were both sacked from their positions. Velasco was dismissed for overseeing the publication of a letter, endorsed by numerous artists and curators, advocating for a ceasefire . Eisen, on the other hand, was let go for simply resharing a post from The Onion on X, condemning widespread apathy for Palestinian lives.

Similarly, Palestinian writer Adania Shibli was stripped of the LitProm literary prize scheduled for presentation at the Frankfurt International Book Fair. The reason behind this decision was her novel, "A Minor Detail," which narrates the account of a Palestinian Bedouin woman who was sexually assaulted by Israeli soldiers in 1949.

Meanwhile, Palestinian artist Emily Jacir’s talk at Hamburg's Banhoff Museum was canceled by the organizers at Potsdam University.

In the midst of the censorship, intimidation, and cancellation of voices supporting Palestinians, the fate of Lebanese artists who have chosen to speak out comes into question.

Many Lebanese creatives, including photographers, art directors, artists, musicians, filmmakers, and designers, have left the country in search of a brighter future, especially in recent years. Are these artists, who have now made names for themselves in the West, jeopardizing their careers by expressing solidarity with the Palestinian cause?

‘I fear my residence permit would be rejected’

Many expat artists have chosen to remain silent, at least on social media.

“I think there was a kind of a tacit agreement between several art institutions to refrain from expressing opinions regarding a ‘political conflict,’” a Lebanese art expert who is based between several European cities said on condition of anonymity.

“But when it became clear that what was happening in Palestine was a humanitarian crisis and a collective punishment of people, with a child dying every 10 minutes, things had to change,” she said. “But unfortunately, this has not been the case as everyone was afraid of speaking up and accused of having certain political affiliations.”

“Personally, it’s my career that’s at stake,” she said.

Another Lebanese artist based in Lebanon also requested anonymity. “My heart is in Gaza, and I am sickened by what’s happening,” he said.

“I have been pro-Palestine since I was a teenager. I am so livid, but I can’t post or say anything as I’m in the middle of renewing my long-stay residence permit,” he added. “One Instagram post could cost me my residence permit.”

"I have family in Beirut, unfortunately, I can't risk my career and my life here,” he added. “We're under scrutiny here in Germany, and there's a silent zero-tolerance policy toward pro-Palestinians; it's easier in cities like London, for example, with demonstrations of hundreds of thousands of people.”

Marwan Kaabour, a graphic designer and art director, who has lived and worked in London for the past 10 years, has been vocal about the Palestinian cause, denouncing Israel’s violence towards Palestinian civilians.

"Of course, I express myself very clearly on Instagram and there is no ambiguity about my position in this terrible situation,” Kaabour told L’Orient-Le Jour.

“In the UK, where I live, things are fortunately slightly different from France or Germany, where there have been more direct threats, censorship and dismissals; although our major arts institutions have not been allowed to make any statements,” he said.

Also based in London is filmmaker May Ziadeh, whose work regularly questions Western and colonialist representations of Arabs.

Ziadeh, who previously lived in Paris, just launched her first short film, Neo Nahda, a feminist queer fiction.

She believes that silencing artists and actors in the field goes back long before Oct. 7.

"I've always been openly supportive of Palestinian liberation. It didn't start on Oct. 7. I've lived in Europe all my adult life,” she said. “This commitment has always been problematic to some extent, even though I've never been fired for it.”

Director Ely Dagher, who won the Palme d'Or at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival for his short file "Waves '98," is outspoken about what he perceives as double standards within artistic institutions.

"We are aware that many Lebanese or Arab artists rely on European and American institutions and funding for their artistic endeavors, and the censorship we are witnessing is unparalleled,” Dagher said.

These art institutions, he explains, are often backed by governments — the same governments supporting Israel in its genocide of civilians, while simultaneously providing humanitarian aid and supporting artistic projects.

"Many of these institutions and funding sources have, for decades, perpetuated the over-mediatization of trauma iconography and fetishized our 'victimization' rather than supporting voices that historically reflect our reality,” Dagher said.

‘Before and after Oct.7’

Photographer and visual artist Ayla Hibri sees a distinct shift in perspective, marking a clear "before and after Oct. 7."

She says there was something problematic in how the Western art world sought to position artists from her region.

"Either they fetishized our struggles, or they wanted our voices muted and our truth suppressed."

With the Oct.7 events, she notes that a veil has been lifted, radically altering her perception. Now, everything is political.

For Hibri, the question of speaking out for the Palestinian cause is not even a consideration; it's a given. This conviction is bound to shape the way she approaches her work in the future.

"Moving forward, I will be meticulous in selecting collaborators, ensuring our principles and values are in sync, and I will boldly speak out about the harsh realities we face,” she said. “Additionally, I am committed to the essential task of recognizing and reassessing the unconscious, internalized aspects influenced by growing up in a colonized place,” she continued.

“I will actively challenge Western hegemony by delving into and fortifying the essence of what it means to be Arab."

Stylist Makram Bitar, who has been based in Paris since 2021 and recently joined the M+A Group agency, said "beyond the horror of the images” from Gaza, what happened prompted him to reflect on the role of artists and creatives.

In Bitar’s view, being being in the feild and creating art hinges on sincerity, which he considers an inherently political act.

Bitar said that claiming sincerity in one's work is incompatible with remaining silent in the face of the Palestinian tragedy. While acknowledging the potential risk openly supporting the Palestinian cause poses on his career, he believes the cost of silence today exceeds any professional repercussions — it is a moral imperative.

Rym Beydoun, the founder and artistic director of the Super Yaya brand, has been actively posting pro-Palestine content on her personal Instagram account. However, she has made a strategic decision to keep her brand's communication relatively neutral.

"When expressing my opinions on social networks, I prefer not to publish on behalf of my brand, as it is an independent entity,” she said. “Moreover, being based and registered in Lebanon, I am already subject to numerous restrictions.”

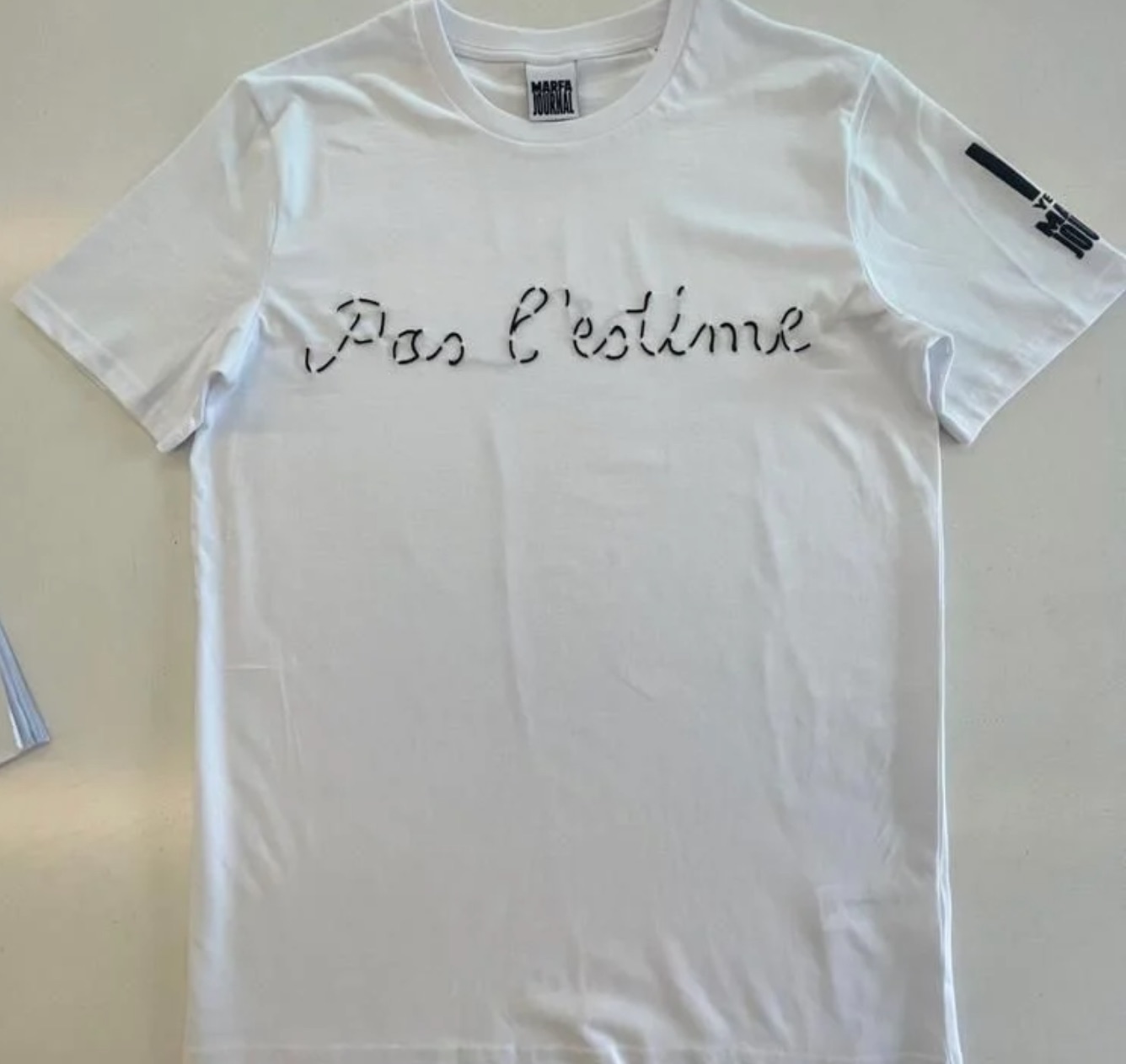

Beydoun added that a considerable percentage of her customers face challenges in sending money to Beirut due to banking sanctions. “While I have taken a stand — starting with the design of a t-shirt for Marfa magazine featuring the embroidered words 'Pas L'Estime'—I am cautious about making a pronounced corporate stance.”

Beydoun's 'Pas L'Estime' shirt for Marfa Magazine. (Rights reserved)

Beydoun's 'Pas L'Estime' shirt for Marfa Magazine. (Rights reserved)

Beydoun added that she was also planning to raise funds, and launch the first episode of Radio Yaya addressing the Palestinian cause through art, poems, and music.

“However, I think it has to remain poetic, as it's an artistic platform that I manage,” Beydoun said. “I use my personal voice, but I'm careful with my brand."

In a similar vein, designer Sabine Ghanem Getty said that she had a project to launch a brand, but it was canceled because the other person involved is firmly from the “opposite camp.”

“Yet I consider my camp to be humanist and humanitarian, certainly opposed to colonialism, but by no means radical,” she said. “Except that it seems that even talking about a ceasefire or Palestinian human rights has become problematic; it's come to this.”

Fear of the financial consequences for supporting the Palestinian cause is not the only apprehension artists are experiencing.

Micheline Nahra, a designer based in the Netherlands, recalled that at the start of the war, she developed anxiety and fear.

“I was actually afraid of people, not only of the world leaders whose speeches we followed on TV, but also of the people around me,” Nahra said. “Living in a place where I know that the government supports ‘Israel's right to defend itself’ created in me this fear of having someone outside my door who also believes in that, because that would automatically put us at different ends of the spectrum of humanity, and I can't conceive of how to move forward after that.”

Raphaëlle Macaron, a Paris-based illustrator who, along with Lebanese-born DJ P-Thugg (Patrick Gemayel), has put several products on sale in aid of Medical Aid Palestine, on the brand's Ya Habibi Market platform.

Macaron recalled facing backlash when she began voicing her stance on Instagram.

"While I'm not in a situation where work contracts have been interrupted, I know I'm already in a position where customers who intended to contact me won't because of my stance in support of the Palestinian cause,” she said.

“From the first day I started expressing myself on Instagram, I received a wave of hate messages from people who followed me and were sensitive to my work,” she added.

Photographer and art director Eli Rezkallah, founder of Plastik Studios and Plastik Magazine, described this human commitment as an almost divisive decision.

"Clearly, when I started openly expressing my support for the Palestinian cause, there was something of a deliberate decision that preceded it,” he said. “And the mere fact that we have to 'decide' to express our support for something as fundamental as human rights says a lot about the state of the world,” Rezkallah said.

“Despite the fact that this is simply about humanity, there seems to be a kind of 'them against us' scenario in the art and fashion world unfolding before our eyes, and I don't understand why or how it's happening.”

Ghanem Getty moved to New York a few months ago, and said the situation there is "very tense."

"When the bombing of Gaza began, I was on Fifth Avenue, where five people had gathered with Palestinian flags, simply to show their support and solidarity with the Palestinian people,” she said. “When I saw them, I simply gave them a gesture of encouragement. On the other side of the street, a man immediately started shouting and calling us terrorists, and other people joined in to encourage him. It just goes to show how tense the atmosphere is here in the US, and this one has an echo on our industry.”

Sabine Ghanem Getty admits that the Palestinian cause has affected her since she was very young. "When I was 12 or 13, I was already seeing on television the horrors inflicted on the Palestinians, and that marked me for the rest of my life. So it was impossible for me to remain silent.”

“Of course, I condemned the Hamas attacks, but especially since then, the illegal collective punishment inflicted on the Palestinian people... I receive direct threats on Instagram as well as other, quieter ones, like the phone call from an acquaintance in New York who was asked to shut me up because I'm bothering them. I'm lucky enough to be privileged and not dependent on anyone for my work, and that's probably what bothers them the most.”

Threats and intimidation hardly surprise Hamed Sinno, artist and ex-frontman of the group Mashrou' Leila. Sinno is used to being targetted every time he voices support for the cause. “As a self-employed worker, I have not experienced professional harassment since Oct. 7. I've received random online threats, it's nothing new and I wouldn't take it seriously, just because I've gotten used to it. I was harassed in the street by a Zionist who spat on my friends and me, with the police looking on without flinching,” he says.

On the other hand, what worried Sinno was what happened next.

“I am already forced to work with Western institutions that might not be aligned with my beliefs and values. I try not to think about it. My beliefs are based on principles, not opportunities. People forget that most of the time, Arabs in America have a hard time just getting a fair chance, just because they are Arab.”

But beyond the urgent commitment to the Palestinian cause, the entire work ethic of these creatives is being called into question.

“I have never been afraid to express my opinions, especially when my sincerity is at stake, and that is why I will refuse to be punished or canceled for having chosen the right side of history, and it is me who, from now on, will filter the people with whom I collaborate,” said Makram Bitar. “As I mentioned, my work can never be sincere if those who participate in it do not share my principles or, in any case, do not demonstrate humanity while we are experiencing a genocide,” he continued.

“I think that when it comes to jobs and contracts, it is high time to think that if the people with whom we will collaborate do not share our values, then there is nothing simply no interest in doing this work. Living in New York, in the middle of wild capitalism, I can understand that some people worry about losing their jobs. People need to make money and simply taking a stand in favor of human lives can unfortunately compromise that. But for me, I think the only way to succeed is to be aligned, value-wise, with the people you work with,” Rezkallah said.

Same thoughts from Marwan Kaabour who said, “I have to be more vigilant and carefully examine the clients who approach me and see who I feel comfortable working with.”

“I will categorically refuse to provide my services to entities or institutions that are clearly not aligned with my views. On the other hand, there is a definite anxiety that once the dust settles, people like me will be punished for the position they took,” he added.

“This is real anxiety, except that in any case, I categorically would not want to collaborate with anyone who does not share my principles. It’s a question of principles, of humanity at this stage,” Kaabour said.

“We should not only speak out, but also cancel any institutions or funds that threaten to punish voices of resistance. We should be the ones to hold accountable the apologists and accomplices of crimes committed against the Palestinian people. Our lives and freedoms are at stake. And if people lose their careers, it's a very small price to pay when others pay with their lives,” Kaabour said.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.