The Franco-Lebanese writer was elected permanent secretary of the Académie française on September 28. (Credit: AFP archives)

In Amin Maalouf’s novel "The Disoriented," Adam, an “incurable foreigner,” constantly feels out of place, both in his homeland and the land of his exile. To Adam, identity transcends geographical boundaries. While others pledge loyalty to their homeland, he remains devoted to an ideal of freedom.

The decision to leave his homeland had been simmering within Adam for a long time, gradually solidifying, until one day he left. Still a young man then, Adam didn't look back and never returned. He left the Orient behind. But the past he once deemed “futureless” still occupied his thoughts now and then, albeit as a distant and sad memory.

Inspired by the life of his creator, Amin Maalouf, Adam is accused by his peers of “betraying” his roots.

However, unlike Maalouf, Adam did not go on to become an archetype of Lebanese success. For one, Maalouf was last week appointed head of the French Academy, the institution tasked with safeguarding the French language. He is the 33rd person to occupy the post since the body's founding under King Louis XIII in 1635.

Maalouf, a poster child of “success on the other side,” is nothing short of legendary. But despite the fame, his core message remains one of humble humanism.

Maalouf, a staunch anti-chauvinist, rejects the shackles of birthplace just as vehemently as the fervor of identity. A man is not a tree with roots, he says. But despite this, just like everyone else, he is a product of a story. Maalouf's story happens to start in Lebanon.

Amin is the son of Ruchdi and Odette Maalouf. He was born in Beirut, the day after the Israeli-Egyptian agreement of Feb. 24, 1949, the first of a series of armistices ending the 1948-49 Arab-Israeli war.

Maalouf spent his early years in Egypt, where his maternal grandparents took refuge, having been driven out of Istanbul in 1915. He stayed there until December 1951, when a series of riots broke out against British tutelage, better known as the “Cairo fire,” which prompted the family to leave.

Years later in an interview with Egi Volterrani, his Italian translator, Maalouf recounted that the Ghosseins, his maternal family, “who until then had felt Egyptian, have come to realize that they would forever be strangers in their own country and that they would have to prepare to leave it.”

The memories of his ancestors, who had been pursued and robbed, shaped him into an “exiled before exile,” someone who always understood that no empire was eternal and no fortune guaranteed, as described by French doctor and diplomat Jean-Christophe Rufin when he was admitted to the French Academy in 2012.

A heart elsewhere

In Beirut, where the Maalouf's settled, young Amin felt like a stranger. His deep-seated attachment to his little mountain village, Ain el-Qabou, did not seem to translate to the capital.

“I constantly had the feeling that I was living [in Beirut] for reasons of convenience, but that I had left my heart elsewhere,” Maalouf said once.

While French novelist and filmmaker Marcel Pagnol celebrated the Provençal hills of his childhood, Maalouf found his muse in his father’s village and its intricate pine-lined lanes, which can be readily identified in his novel “Rock of Tanios,” which is infused with the traditional “hakawati” storytelling of his youth.

In his idyllic sun-soaked village, where children explored amidst the rocky terrain, Boutros, Maalouf’s grandfather, who identified as an Ottoman citizen, established a school.

“Without him [Boutros], we would have all been left tending to our silkworms,” said Youssef Ghossoub, a friend of the family, to AFP in 1993.

The Maalouf family was Protestant and naturally, Ruchdi Maalouf gravitated toward the American University of Beirut (AUB) which was founded by the American Protestant Mission to Lebanon. Ruchdi pursued journalism and later obtained a philosophy doctorate in the United States.

Ruchdi was a multifaceted individual — a brilliant journalist, poet, writer, art critic and painter. He was the director of the al-Jarida daily and was a renowned lecturer, who emphasized the primacy of culture over politics in his teachings.

Despite English being the dominant language at home, Maalouf embarked on his educational journey in French in 1955, attending the Jesuit “Notre-Dame de Jamhour,”— a crucial condition set by his Greek-Catholic mother when she first married his father. His three sisters, on the other hand, were sent to the “École des Sœurs-de-la-Charité – Besançon” school in Beirut.

Every morning, young Maalouf waited for the school bus between the Badaro neighborhood and the National Museum in Beirut.

Maalouf's sixth grade class at Notre-Dame de Jamhour (1959-1960). He appears front row, second from the left. (Photo DR)

Maalouf's sixth grade class at Notre-Dame de Jamhour (1959-1960). He appears front row, second from the left. (Photo DR)

“He was an excellent student,” said Joseph Maila, Maalouf’s friend of over 60 years who was his bus and class companion. Today, Mailai is a professor of international relations at the Essec Business School in Paris. “He was studious and cultured, having a strong command of French and Arabic, showing keen interest in literature, history and geography rather than in sciences.”

It was the mid-1960s. The Jamhour school offered an academic environment with stringent standards and commitment to excellence and the Jesuit fathers’ extensive library served as a source of intellectual awakening for its young students.

At home, a teenage Amin was enraptured by his cutting-edge radio. In the class of ‘66 yearbook, a brief passage accompanied his photo, depicting the bespectacled teenager: “Amin Maalouf, naturally reserved, with a strong penchant for geography and politics. His specialty lay in staying attuned to news from around the world, in multiple languages. His future path: journalism.”

‘We wanted to change the world’

In 1966, Maalouf embarked on his academic journey at Saint-Joseph University (USJ) in Beirut, where he studied sociology and economics. Simultaneously, at the École des Lettres (faculty of literature), he voraciously consumed the timeless classics of Western literature.

These years were predominantly characterized by the fervor of student activism, political turmoil and aspirations for change. The 1967 Arab-Israeli war further destabilized an already precarious equilibrium in troubled Lebanon.

As the 1970s loomed, Lebanon had not yet plunged into the mire of armed conflict, but its youth were already in open rebellion against the political establishment and the deficiencies of confessionalism.

“We wanted to change the world,” said Tarek Mitri, a friend of Maalouf’s from those times. Mitri is a former culture minister and president of Saint-George University. “That was our generation, we had big dreams.”

At a time when the Palestinian presence divided public opinion and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) gained strength in the wake of the 1969 Cairo Agreement — under which the presence and activities of Palestinian guerrillas in southeastern Lebanon would be tolerated and regulated by the Lebanese authorities — Maalouf and his friends were part of a generation that was rapidly becoming politicized.

“We were a group of young people who carried out protests, ” Maila said.

But even at the height of his political engagement and activism, Maalouf remained true to his level-headed nature.

“He was someone who thought things through, who didn’t get carried away,” Mitri said. “He was never an activist who was blinded by the cause he was defending.”

At USJ, he also crossed paths with Andrée, a young special education teacher, whom he married in 1971. Their union brought forth three sons.

Following in his father’s footsteps, that same year, Maalouf joined the editorial team of the daily Annahar newspaper. Even after relocating to France in 1976, he continued to contribute to the publication.

However, his aspirations extended far beyond his work at Annahar. He yearned for distant lands, novel landscapes and stories grand and small.

His initiation into the world of journalism at Annahar was a stepping stone. There, he covered global current events and honed his reporting skills. His assignments took him to places like Ethiopia and Vietnam. He traveled across the vast expanse of Africa.

“When he returned home, we would spend hours enraptured by his accounts of what he had witnessed and the profound reflections these experiences stirred within him,” Mitri said.

Shortly after returning from his reporting assignment in Asia, he witnessed the Ain al-Remmaneh massacre on April 13, 1975, which was widely regarded as the catalyst for the Lebanese 1975-90 Civil War.

The harrowing scene unfolded below the windows of the Maaloufs’ modest apartment, compelling the couple to flee to the mountains.

“He was probably the only one of us to realize that the war will drag on indefinitely,” Mitri recalled. “He told us, ‘It’s going to be a long time, I’m leaving.’”

He left for Paris, initially alone, where he secured a small apartment and eventually landed a position as a journalist with Jeune Afrique magazine. He would later rise to the role of its editor-in-chief. His family joined him in Paris shortly after.

The year 1976 marked a new chapter in Maalouf’s life, one that was written in French. Having launched his career in Arabic, he later acknowledged that the shift from one language to the other was a consequence of “life’s hazards.”

Goncourt Prize 1993

“It’s likely that if I hadn’t been forced to leave my country, I wouldn’t have devoted my life to literature,” Maalouf wrote in his book “Origins.”

“I had to lose my social bearings and all the obvious ambitions associated with my background, for me to seek refuge in writing.”

In 1983, he published his first historical essay “The Crusades Through Arab Eyes”, a book that made a lasting impression as it narrated the Crusades through the perspectives of Arab writers of that era.

It was his debut novel “Leo Africanus” (1986), that propelled him into the literary limelight.

Enriched with diverse origins, Maalouf finds inspiration in the narratives woven through generations by his ancestors.

In “The Rock of Tanios,” his homeland transcends its role as a backdrop and emerges as the center of the story's narrative.

Published three years after the end of the Civil War, the novel won great acclaim in France before it clinched the prestigious Prix Goncourt award in November 1993.

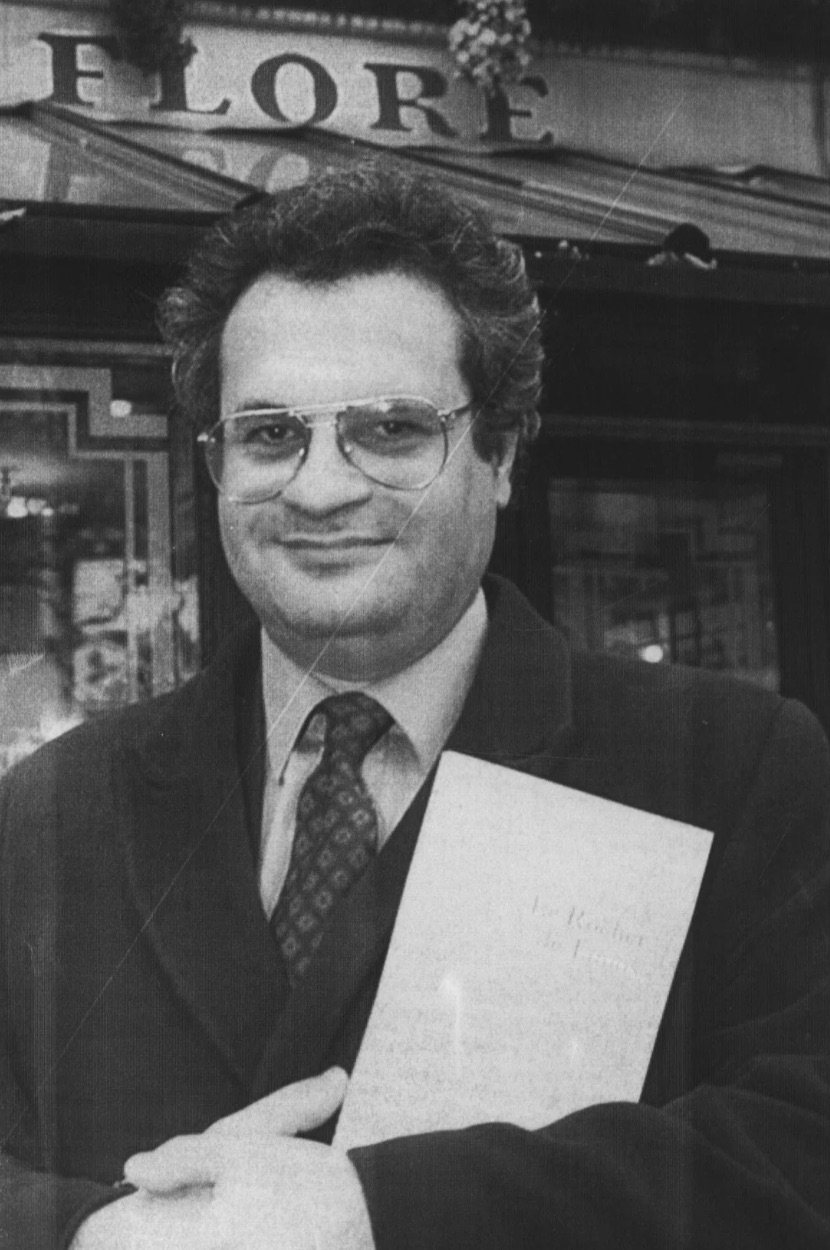

The writer receiving his Goncourt prize in front of the Café de Flore, in Paris, November 8, 1993. (Credit: AFP)

The writer receiving his Goncourt prize in front of the Café de Flore, in Paris, November 8, 1993. (Credit: AFP)

“I needed to allow ideas to mature,” Maaoulf told Prestige Magazine in an interview. “It was only then that I sensed the moment had come to share them.”

Shortly after, Maalouf returned to Beirut for the first time in 17 years.

“When the prize was announced, people [in Lebanon] reacted in an incredible way ... cars were honking in the streets,” Maalouf told Volterrani. “It was as if after years of estrangement and misunderstanding, my beloved city [Beirut] had loudly shown me her affection; I had to go to her, and hug her.”

On Nov. 30, 1993, Maalouf declared his intention to “split (his) time between France and Lebanon,” in an article he wrote in L'Orient Le-Jour. He expressed his vision of having a family home in Ain el-Qabou as a counterpart to his retreat on the Ile d’Yeu, where he spent long months writing. It was wishful thinking.

“I have lived on the French soil for 22 years, I drink its water and wine, my hands caress its old stones everyday, I write my books in French and France could never again be a foreign country,” wrote Maalouf in the “Name of Identity: Violence and the Need to Belong.”

“Half French and half Lebanese, then? Not at all! The identity cannot be compartmentalized; it cannot be split in halves or thirds, nor have any clearly defined set of boundaries,” he wrote. “I do not have several identities, I only have one, made of all the elements that have shaped its unique proportions.”

A writer whose works have been translated into more than 50 languages, Maalouf nevertheless maintains a level of discretion that sets him apart from the prevailing trends.

“He’s not one to engage in idle chatter; he ponders deeply and, when asked something, he takes the time to respond with thoughtfulness and composure,” said Amin's nephew Ibrahim Maalouf, a famous French-Lebanese trumpeter. “I’ve never seen him lose his temper.”

Perhaps it’s in “Origins” that Maalouf truly reveals himself. In this quest for identity, delving into the roots of his family that trace back to the 19th century, he recounts his own life and those of his loved ones, all while touching upon his own personal wound—the wound of “exile.” He poignantly shared, “At times, I say that my homeland is writing, and it’s true... that’s where I settled, where I breath, and where I will ultimately rest.”

Rolling the “Rs”

On June 23, 2011, just as the region was experiencing a brief burst of hope in the wake of the Arab Spring popular uprisings, Maalouf was initiated into the French Academy, created in 1634 by Cardinal Richelieu, the chief minister to King Louis XIII, to safeguard the “spirit of the French language.”

After several unsuccessful attempts, Maalouf was finally elected as the Claude Lévi-Strauss chair, a position honoring an “emblematic” author who he was especially fond of in his student days.

Some 20 of his childhood friends made the journey from Beirut to witness the traditional sword presentation. Within the walls of the institution, Maalouf’s accent reverberated, but he vehemently rejected any notion of exoticism.

“Is this not how La Bruyère, Racine and Richelieu, Louis XIII and Louis XIV, and Mazarin, of course, expressed themselves, and before them, before the academy was created, Rabelais, Ronsard and Rutebeuf?” Maalouf said in his acceptance speech. “Rolling the Rs is not coming to you; it’s coming back to you.”

As Arab countries headed ever more surely toward a foretold “shipwreck,” the academy served as a refuge for Maalouf, the last island of resistance against the accelerating march of history.

Maalouf embodied “a blend of wisdom, experience and love of the institution,” said Daniel Rondeau, writer, fellow Academician and friend.

Maalouf is a “patriot of the academy,” which he loved to the point of having made it the subject of one of his latest essays (Un fauteuil sur la Seine: quatre siècles d'histoire de France), and of which he is now the perpetual secretary.

At the same time, the distance separating him from his homeland became more apparent. In 2013, at the Salon du livre francophone de Beyrouth (The French-language book fair of Beirut), he declared his dream of a Lebanon where coexistence prevailed, a “dream that has ought to come true.”

But as the country sunk into an endless whirlwind of crises, he watched helplessly as the idea of a Lebanese nation collapsed. Maalouf hasn’t returned to Lebanon since and has turned down all professional invitations, as disclosed by an acquaintance who refused to be named. Perhaps his disenchantment translated into detachment.

Lebanon, Maalouf was celebrated by most Lebanese and elevated to national icon status, alongside the likes of Feyrouz and Khalil Gebran. After an interview he gave to the Israeli channel i24 in June 2016, he fell out of favor with a section of the Lebanese populous.

Maalouf did not comment on the incident.

Many others, however, would do so on his behalf.

“If Maalouf didn’t pay attention to the channel’s identity, he ought to apologize for his blunder to the Palestinians, the Lebanese people, and the entire Arab community,” said the pro-Palestinian Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement.

March 8 media outlets also capitalized on the controversy, using it to initiate a campaign against him. The pro-Hezbollah daily al-Akhbar went so far as to label Maalouf “Leo the Israeli.”

The years to follow marked his gradual sense of detachment from public affairs.

“Like all those who have aspired for change, he is a disillusioned man,” Mitri said.

Nowadays, Maalouf mostly observes the world from the Quai de Conti in Paris, where he attends the weekly gathering of the French Academy, of which he was recently elected leader, every Thursday.

“The country whose absence fills me with sorrow and preoccupies me is not the one I encountered in my youth; it’s the one I envisioned but never witnessed," said Adam, in "the Disoriented." Perhaps Adam and Maalouf are not so different after all.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient Le-Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.