BDL Governor Riad Salameh in Beirut, December 20, 2021. (Credit: Joseph Eid/AFP)

BEIRUT—On Aug. 10, the United States government made headlines in Lebanon by sanctioning former central bank governor Riad Salameh, his brother, son, assistant, and partner for corruption and undermining the rule of law in Lebanon.

Just six days later, the US sanctioned Green Without Borders and its director Zuhair Nahla, claiming that the self-described environmental NGO in fact works in service of Hezbollah, which the US considers a terrorist organization

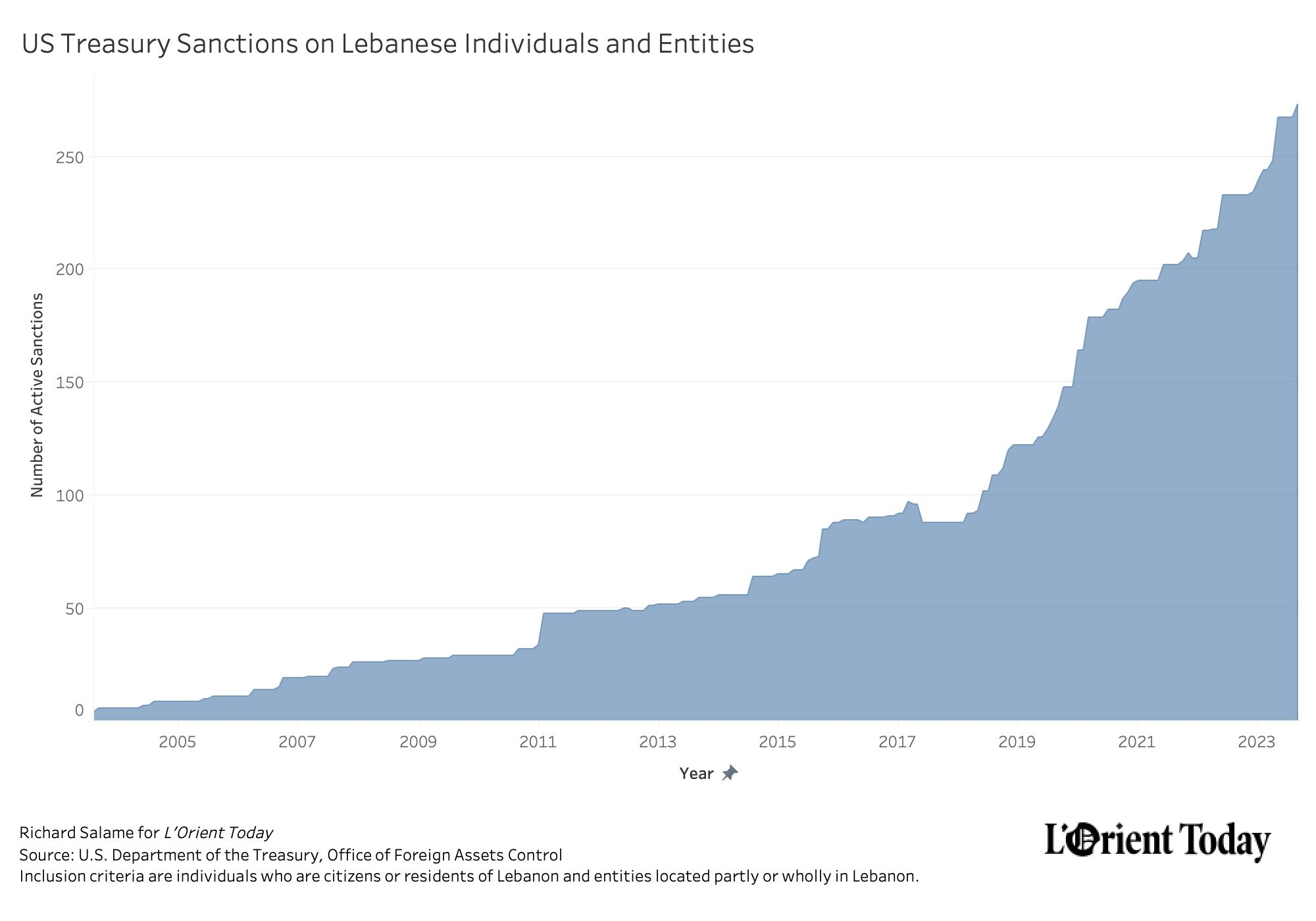

The moves brought the number of Lebanese individuals and entities under current US sanctions up to 273 — the largest figure in at least 20 years — based on L’Orient Today’s analysis of 20 years of US sanctions designations.

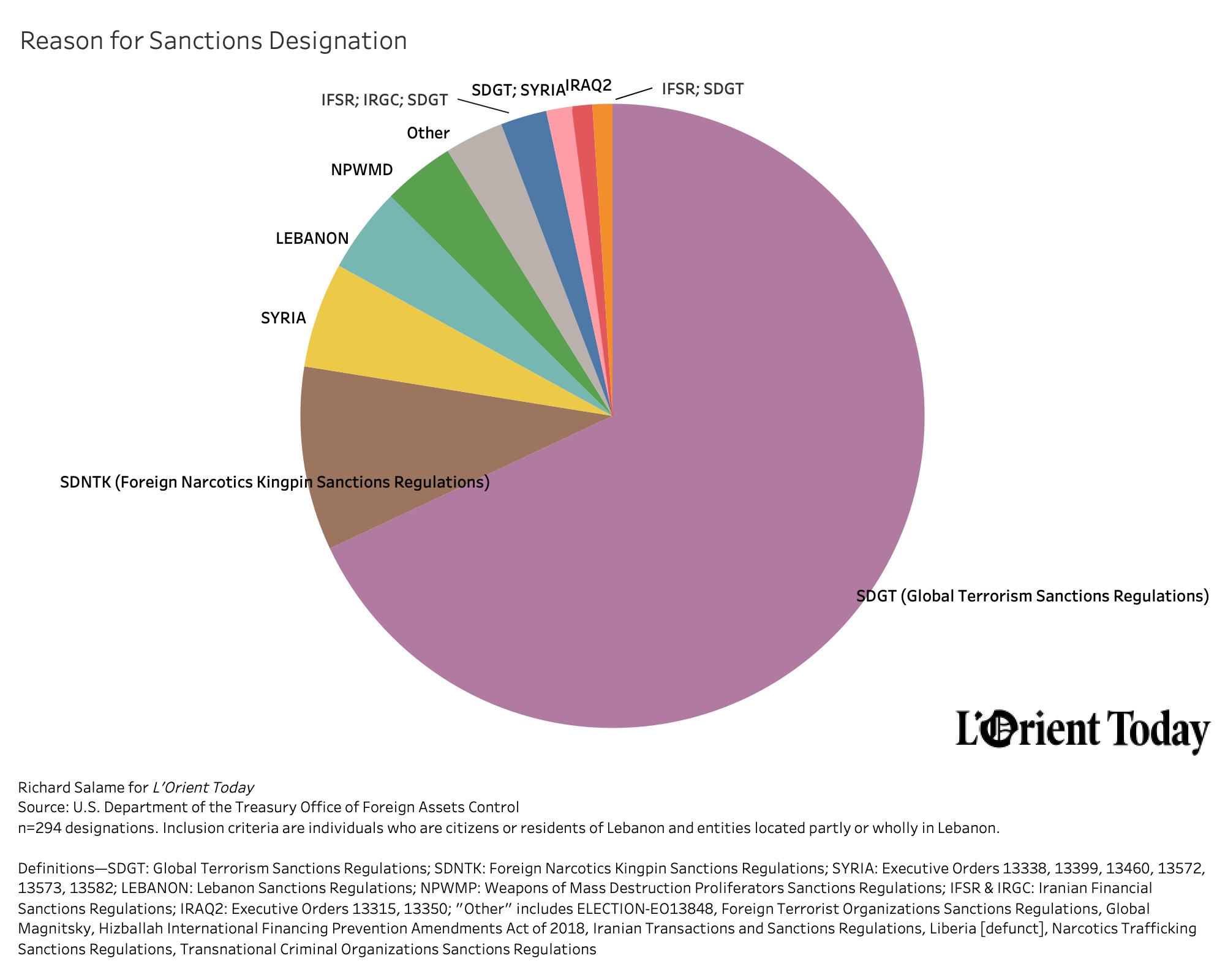

The two rounds of August 2023 sanctions highlight the two main faces of US sanctions in Lebanon: corruption-related sanctions that are less common but often target high-profile individuals, such as the head of Free Patriotic Movement Gibran Bassil in November 2020; and the more numerous sanctions related to what the US considers terrorism, particularly Hezbollah members and affiliates.

The US has also issued two other broad categories of sanctions in Lebanon: narcotics and ties to the Syrian government.

Inclusion on the US Office of Foreign Assets Control sanctions list does not mean that an individual has been charged with or convicted of a crime in any jurisdiction.

Sanctions related to “terrorism”

Of sanctions imposed in the last 20 years on Lebanese entities, 68 percent of targets were labeled “specially designated global terrorists” — a legal classification that arose in the immediate aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks and, broadly speaking, consists of people and organizations the US government claims present a risk to US security—or its foreign policy or economy.

This designation also explicitly includes people who “knowingly provide significant financial, material, or technological support” to Hezbollah and any of its affiliates, including Jihad al-Bina (a party-affiliated construction company), Al-Manar TV and al Nour Radio.

“With sanctions targeting Hezbollah, I think the most credible justification I’ve heard for those is that their aim is attritive,” says Sam Heller, a researcher with US-based think tank Century International. “Not that they are intended to somehow deal a deathblow or have any sort of decisive effect on Hezbollah, but rather that they are meant to deny the organization access to some resources and sources of support over time and to at least incrementally weaken the organization.”

A US embassy Beirut spokesperson, in written comments to L’Orient Today, touted this program as successful, saying, “US sanctions have so significantly impaired Hizballah funding streams that the organization has reduced salaries for its military arm and media efforts and publicly solicited donations.”

Three sitting members of Lebanon’s Parliament are currently sanctioned under the specially designated global terrorists program: Ali Hassan Khalil (Marjayoun-Hasbaya/Amal), Amin Sherri (Beirut II/Hezbollah), and Mohammad Raad (Nabatieh/Hezbollah).

Other major programs

An additional 10 percent of US sanctions fall under “Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Sanctions Regulations” (SDNTK), which relate to international drug trafficking. The 28 sanctions designations under this program were made between 2011 and 2019. Thirteen were lifted in 2017 and 2018.

The next largest category of sanctions targets falls under a collection of Syria-related sanction laws, some of which date back to May 2004, when the George W. Bush Administration imposed sanctions on Syria related to its control over Lebanon and its “undermining” of the US occupation of Iraq.

But no Lebanese individuals and entities were sanctioned under Syria-related laws until December 2014, two years into the Syrian Civil War, by which point the US had added new sanctions criteria in response to the conflict. Sixteen Lebanese individuals and entities are currently sanctioned under the expanded Syria program.

Sanctions for “undermining” the state

The Lebanon sanction program, established in August 2007, was created following US President Bush’s determination that the actions of “certain persons” to “undermine” Lebanon’s government and institutions, “to contribute to the deliberate breakdown in the rule of law in Lebanon,” and to “undermine Lebanese sovereignty” constituted “an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States.”

A primary target of this program was individuals the US said contributed to “Syrian interference in Lebanon.” The program was used to sanction Lebanese politicians Wiam Wahab and Assaad Hardan in 2007, who were accused of working with Syrian officials to “undermine Lebanese sovereignty.”

The Bush-era executive order wasn’t used again until 2021 when businessmen Jihad al-Arab and Dany Khoury, and MP Jamil Sayyed were sanctioned for allegedly undermining the rule of law in Lebanon.

Recently, this sanctions program was again used to sanction former Central Bank Governor Riad Salameh alongside his brother, son, and two associates on similar allegations.

In an accompanying press release, the US positioned itself and its allies, the United Kingdom and Canada, as defending the Lebanese public against the political class, saying that the three countries share a “vision of a Lebanon that is governed for the benefit of the Lebanese people and not for the personal wealth and ambition of Lebanon’s elite.”

“Among the main audiences [for corruption sanctions] is the Lebanese public to whom the United States is attempting to convey its own objectives and positions in Lebanon,” says Heller.

“With the anti-corruption sanctions… I think the objective there is more one of signaling. I think there it's likely intended to signal to the Lebanese public and the broader Lebanese political class the seriousness of the United States about corruption and reform in Lebanon and then the unacceptability of continued business as usual in Lebanon going forward,” adds Heller.

But sanctions only go so far in advancing the stated objectives of the US: “I think worth bearing in mind that these objectives, even if these sanctions are successful in realizing them, the effect is nonetheless marginal,” Heller continues. “This is only going to make a difference on the margins. It can only be a compliment to a fuller policy. They don’t amount to a policy in themselves.”

The aforementioned US embassy spokesperson defended the efficacy of sanctions, saying, “Sanctions are a fundamentally important tool to advance US national security interests. Sanctions are meant to encourage good behavior and promote accountability for corrupt actions committed by bad actors.”

“At the same time, sanctions are just one tool in our toolbox. The United States’ engagement with Lebanon and in support of the Lebanese people is comprehensive and includes high-level diplomatic engagement, humanitarian and development assistance, support to the security services, arts and culture programming, and more,” the spokesperson added.

“The United State’s use of sanctions in Lebanon is just a reflection of successive US administrations increasing reliance on sanctions as an implement of foreign policy globally,” says Sam Heller. “In some instances, the sanctions may be designed to achieve a more defined material impact; in other instances, they may just be a relatively low-cost, low-effort means of signaling US policies, US positions, either to an international audience or maybe to a domestic American one.”

The growing use of US sanctions worldwide

L’Orient Today focused its review on American sanctions because the US leads the world in the use of sanctions, accounting for 42 percent of globally deployed sanctions since 1950, according to the Drexel University Global Sanctions Database.

The next largest users of the tool are the European Union at 12 percent of global sanctions and the United Nations with 7 percent.

US sanctions are uniquely powerful given the economic might of the United States. The US is the world’s largest national economy, the world’s largest importer, and its second-largest exporter.

The US Treasury Department, the main administrator of sanctions, also controls the US dollar, the world’s primary reserve currency, and has powerful leverage over the SWIFT financial transfer system, which handles “half of the world’s high-value cross-border payments,” according to the Financial Times in 2018. That puts a considerable amount of muscle behind a US sanctions designation, although some current or former US officials have expressed concern that overuse of sanctions could erode their power.

A 2021 US Treasury review found that, after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, sanctions became a “tool of first resort to address a range of threats.” Between 2000 and 2021, the number of US Treasury sanctions designations exploded from 912 to 9,421, the review found— a 933 percent increase.

The 2021 US Treasury review of sanctions’ effectiveness noted the risk of sanctions undermining the US dollar’s global reserve currency status—which it said is under threat from digital currencies and “adversaries seeking to build new financial and payments systems intended to diminish the dollar’s global role.”

The development bank set up by the BRICS countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa—announced Tuesday that it plans to begin lending in South African Rand and Brazilian Real to reduce reliance on the US dollar and the centrality of the US in the international financial and trade system.

It will also issue its first Indian rupee bond in October. The bank aims to reach 30 percent of its lending in members’ local currencies by 2026. Talk of a unified BRICS currency was, raised again on Wednesday by Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva at the BRICS summit but has apparently not resulted in a concrete plan.

Gustavo de Carvalho, a policy analyst on Russia-Africa ties, recently told Al-Jazeera that Global South countries are concerned about the risks of “engaging with one currency globally that may be utilized for political purposes.”