There are 300 deer births a year on the Aana reserve. (Credit: João Sousa)

“It’s time to eat!” exclaimed Fouad Nassif, as the sun began to descend behind the mountains. In the quiet of the west Bekaa Valley, near Ammiq, deer herds at Aana Reserve begin to frolic in the fields. Founded 25 years ago, Aana Reserve covers 60 hectares and shelters nearly 300 animals — mainly fallow deer, some bighorn sheep and ibexes.

A resident of Beirut, Nassif regularly makes the trip to the reserve to feed his animals. He also entrusts this task to friends on site.

Wearing a red keffiyeh, Abu Hassad, one of the reserve employees, awaits the animal’s arrival. He leans out the window of a white pick-up truck, where Malek, another employee, sits in the back, surrounded by four bags of maize. On the arid hills in the distance, some spotted female deer pause in their cavorting to raise their snouts.

“Der der der,” shouts the driver between honks of the horn, haranguing the herd as they arrive and begin to follow the truck.

At the top of the hill, a dozen rock-colored ibexes shake their vaulted horns and answer the call.

“They are more shy than deer,” explains Abu Hassad.

Well in the shadow of the hillside, the vehicle pauses briefly before descending slowly, allowing Malek to pour out grains of corn along the way. Quickly, and with a certain elegance, the animals jostle to take their place along the trail of corn.

‘There are no more animals in my country’

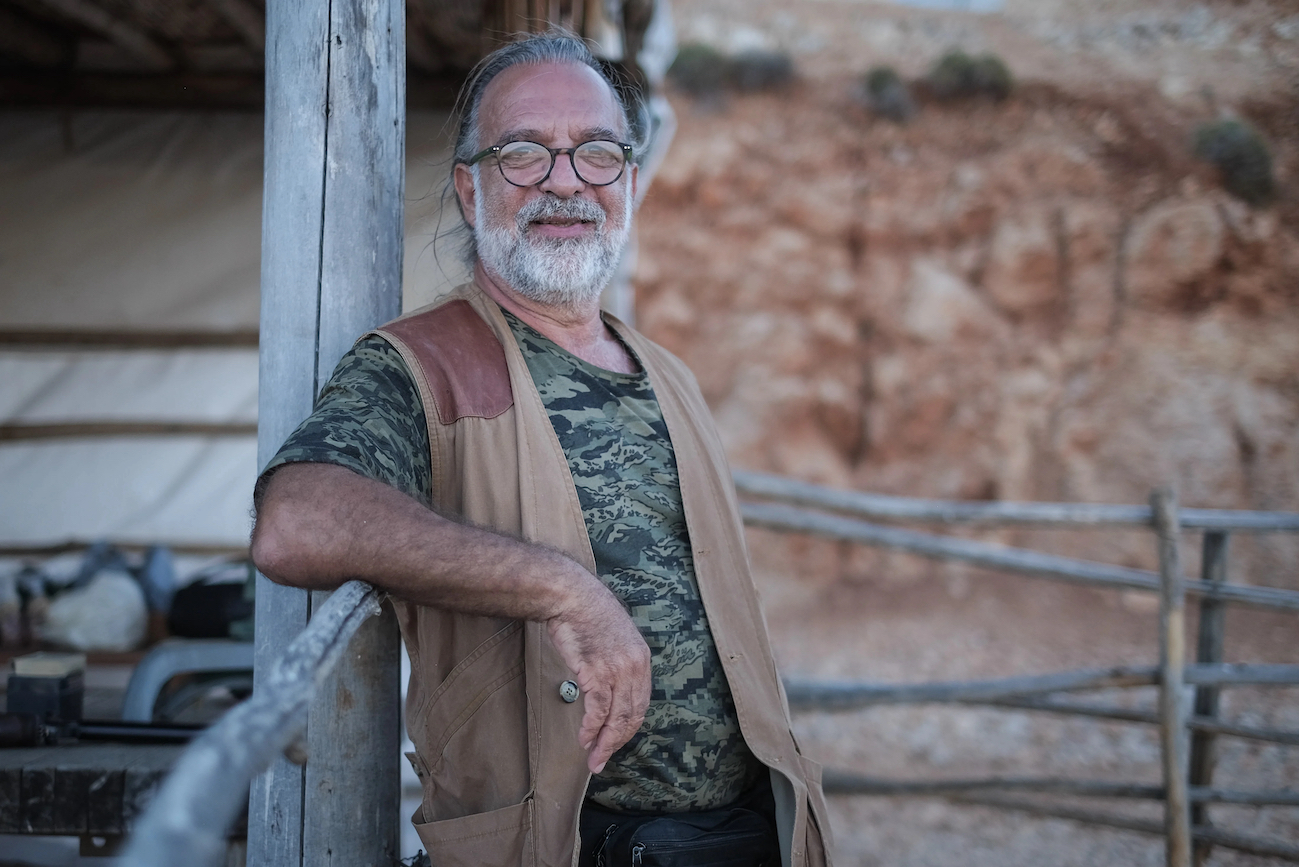

Fouad Nassif, hunter and breeder of fallow deer, mouflon and ibex, in the Bekaa Valley. (Credit: João Sousa)

Fouad Nassif, hunter and breeder of fallow deer, mouflon and ibex, in the Bekaa Valley. (Credit: João Sousa)

In his camouflaged hunter jacket, Nassif blends into the landscape.

“At the beginning of the century, the Great Famine (1915-1918) forced the Bekaa people to hunt en masse. Since then, there have been no deer,” he explains.

In the late 1990s, Marada movement leader “Sleiman Frangieh offered me some fallow deer of Mediterranean origin,” Nassif recalls.

These deer form the core of his herd.

With nearly 300 births per year, the goal is clear: it is not only to raise the animals, but to repopulate Lebanon with its natural fauna. “I reintroduce these species that nature has lost for long,” Nassif says, as he gives a piece of bread to one of the deer.

Nassif arranges to have animals released into the wild. In the reserve of Bneshaai, in the north of the country, he’s released between 200 and 250 animals from his herd yearly. In the future, he hopes to find new protected areas where he can extend this rehabilitation project. A project with the Chouf’s Barouk cedar reserve is underway.

“We have built a pre-release fence to put deer and ibex in while they adapt to this new space where they will soon be released,” Nassif says.

Popular with tourists for the beauty of its landscape, the Aana reserve attracts the most curious of tourists. Nassif welcomes them in groups of no more than eight and makes sure that no one has visited a farm recently to protect the animals from diseases.

“As much as possible, I want to leave them a wild population.”

A hunter who knows how to hunt

Nassif says he releases 200-250 of his animals into the wild annually. (Credit: João Sousa)

Nassif says he releases 200-250 of his animals into the wild annually. (Credit: João Sousa)

Besides feeding the animals in the reserve, a “nursery,” as he calls it, Nassif also ensures their protection. Hyenas, wolves and jackals may be endangered in Bneshaai, but in Aana they are not.

“The only predators are wild cats and dogs abandoned by hunters,” he says. To ensure they don’t prey on his deer, Nassif set up traps along the reserve’s borders.

He knows hunting very well. Nassif has hunted in Europe and believes that culling helps ensure biodiversity.

“Good hunters only kill old males,” he says, “and follow regulations.”

As a member of Lebanon’s National Hunting Council, Nassif was consulted in the wording of Law No. 580, drafted in 2004, which sets out protocols vis-a-vis which species can be hunted and the season when it is legal to do so (from September to January). The law is currently in legislative limbo and remains unenforced.

Unfortunately, some hunters do not abide by the rules.

Nassif is not worried about the animals bred in Aana. “We only put them in protected areas,” he says reassuringly. In addition to “being part of the beauty of nature,” deer are an important part of Lebanese fauna.

Protected at the Aana reserve, these deer thrive.

This story first ran in French in L’Orient-Le Jour, translated by Joelle Khoury.