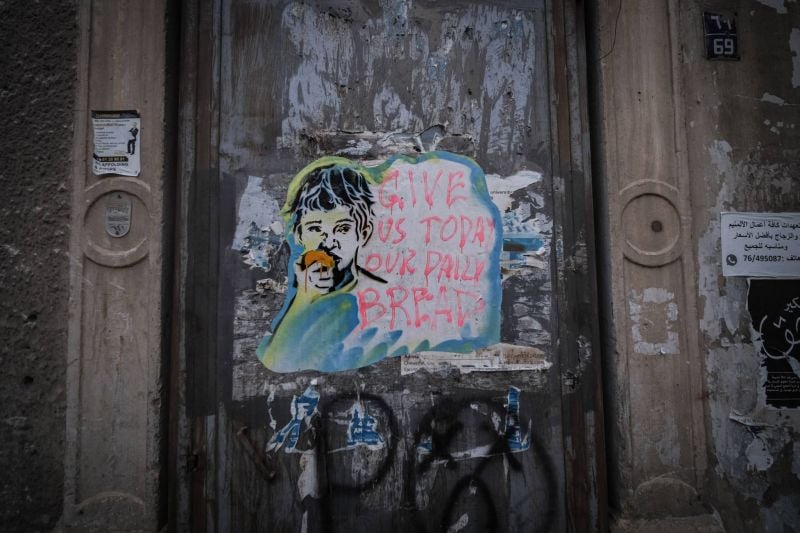

Street art by Brady Black, reading "give us today our daily bread," Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today file photo)

BEIRUT— Under an October 2020 law, all Grade One, Two, and Three civil servants — roughly corresponding to managers and supervisors — all elected politicians and all civil servants whose work has financial consequences regardless of grade, are required to declare their assets and financial interests.

Lying on the declaration is a crime punishable by up to one year in prison and fines ranging from 10-20 times the minimum wage.

These declarations can be audited by competent judicial authorities and by the new National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC), which finally received its full six members in January 2022.

A new report by government transparency watchdog Gherbal Initiative in partnership with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), found that a key impediment to the law’s enforcement by the new NACC will be the lack of a unified list of declarants.

Report findings

Prior to the creation of the new NACC, many separate offices and ministries were designated by the 2020 asset declaration law to receive declarations from the various branches of the government.

Gherbal queried 27 entities for information about the number of officials under their jurisdiction subject to the requirement and the number of declarations received, but six administrations did not respond in addition to two more that refused to provide the required information.

Among the administrations that did not provide information, according to Gherbal, were major public sector bureaucracies including the ministries of education, interior and defense, and core service-providing bodies such as the ministries of energy and water, telecommunications, and public works and transport.

A further nine administrations provided incomplete information, according to Gherbal, including the Finance Ministry, the central bank and the cabinet’s secretariat.

Based on the 19 administrations that did reply either partially or completely, Gherbal determined that 10,849 public officials submitted their declarations; however, it was unable to determine how many other officials might have been subject to the requirement but failed to submit their declaration.

It is one obstacle among several that need to be overcome in order to fully implement the declaration system.

Anti-corruption and the (ongoing) birth of the NACC

The 2020 asset declaration law and the separate 2020 law to create the NACC are part of a larger push that’s been unfolding, at least legally. Some observers have voiced skepticism of this push, arguing that corruption is a structural feature of the sectarian political system and cannot be defeated without a broader overhaul of the political system.

But from 2015’s money laundering and terrorism financing law to 2017’s access to information law to 2021’s public procurement law, Lebanon has passed several “consequential laws that make up a robust and comprehensive legal framework for combating corruption,” said researcher Ali Taha of the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.

The NACC is also mandated to take over the receipt of asset declarations and investigate irregularities in them pursuant to the 2020 asset declaration and illicit enrichment law, which Taha called “an improved mechanism” for disclosures compared to the previous illicit enrichment laws, most recently the 1999 law.

The 2020 law has three key benefits, Taha said: it elevates illicit enrichment to a full-fledged legal offense on its own and broadens its definition, it provides a monitoring mechanism, and it allows for prosecution of offenses without a statute of limitation.

Unfortunately, Taha said, the asset declarations are not public and are only available to the NACC, with their public disclosure made a criminal offense except in cases specified by law.

“The reasoning behind blocking access to the ‘Holy Grail’ of what should be public information seems to be the usual ‘security concerns’ argument, which is, as usual, unconvincing,” he said.

According to the World Bank 55 percent of countries make asset declarations public, which it says, “increases scrutiny and complements the enforcement efforts of the verification agency and “helps to build public sector integrity and promotes public trust in the government.”

The NACC was created by law 175/2020 in order to monitor the implementation and investigate the violations of a host of anti-corruption laws passed in recent years, including the 2017 access to information law and the asset declaration and illicit enrichment law of October 2020.

Despite being created by a 2020 law, the six seats on the NACC were only filled by a cabinet decision in late January 2022. Mohammad Chamseddine, a researcher at Information International, previously told L’Orient-Le Jour this delay showed a “lack of seriousness of the state in its will to fight corruption.”

In April of that year the NACC finished drafting its internal rules of procedure and submitted them to the State Council, but these were not yet approved as of late June 2023, according to a report by the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, leaving the appointment of an administrative staff on hold.

On Tuesday, 15 civil society and private sector organizations issued a statement calling for the government to release NACC’s internal rules of procedure and provide it with resources, calling it “unacceptable that the internal rules continue to be stuck for more than a year in a bureaucratic process that has currently made it languish in the drawers of the Ministry of Finance.”

UNDP Resident Representative Melanie Hauenstein told L’Orient Today that “today, despite all efforts, the NACC is not fully functional, and thus unable to build an effective assets and interests’ declaration system” noting the lack of approval of its bylaws and the fact that its full budget has not been released to it. A digital system is also needed, she added, and UNDP, with funding from the European Union and the government of Denmark, is involved in the development of a website for NACC and the introduction of e-signature forms.

Despite the lack of approval of the NACC’s bylaws and the absence of staff, NACC has started to receive a few asset declarations from new hires and recent resignations, says Assaad Thebian, head of Gherbal. “Because, by law, after the establishment of NACC, it becomes the reference in which those new employees submit their forms.”

Communicating with L’Orient Today by email, Hauenstein said since the appointment of the commission’s members the NACC has received 194 declarations: “1 from a former President of the Republic, 51 Former Deputies, 128 New Deputies, and 14 Public Employees.” She added that UNDP will hold workshops to facilitate a “gradual transfer of all declarations to NACC.”

NACC’s president Judge Claude Karam did not respond to questions about the status of the bylaws and staffing and whether it has begun receiving declarations.

In addition to the “cautious optimism” surrounding the NACC’s formation, other initiatives have continued in parallel.

The judiciary and others take aim

Between 2012 and 2018 — not including 2016 and 2017 — 289 public officials received penalties from the Central Inspection for misconduct, according to the state’s 2020 anti-corruption strategy. Nine penalized officials came from the top two grades in the civil service hierarchy, which contain supervisory or managerial positions.

During the same time period 102 public officials were convicted by the Higher Disciplinary Committee of misconduct ranging from embezzlement to acceptance of bribes to tampering with official school exams. Some of them may also have been among those who received Central Inspection penalties. Of the 102 Higher Disciplinary Committee convictions, there were 17 dismissals, with other defendants receiving demotions, delayed promotions, suspensions or warnings.

More recently, there have been sporadic, high-profile investigations into corruption, resulting in numerous arrests. In November 2022 the Mount Lebanon public prosecutor began investigating bribe-accepting among employees of the region’s land registry offices. Some 35 employees have been arrested in the probe, with many of them later being released on bail pending trial. As of early this year, some 22 other individuals were sought but had not been apprehended.

Also starting in November 2022, a wave of arrests swept across the vehicle registration centers of the Traffic and Vehicles Management Authority, with tens of employees charged with bribe-taking. The authority’s head, Hoda Salloum, has been charged with “professional negligence.”