Street art by Brady Black, reading "give us today our daily bread," Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today file photo)

BEIRUT—On June 19, 2023, 29 MPs issued a statement opposing the parliamentary session called by Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri to vote on appropriations to fund public sector conditional salary bonuses.

The MPs, largely drawn from the Kataeb and Lebanese Forces blocs, were joined by Waddah Sadek, Michel Douaihy, and Marc Daou from the Forces of Change bloc.

Besides complaints about the constitutionality of the session, they cited 2017’s public sector salary scale increase, which they called “ill-considered,” and said, “accelerated [Lebanon’s] collapse.”

Is it true?

“The 2017 salary law is not the sole ‘accelerator’ of the collapse,” says Sabine Hatem, a senior economist at the Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan. “All the fundamentals of Lebanon’s economic model were weak and pointing to a sizable crisis in the making.”

“However, the passing of the salary law did serve elite capture over public resources (instead of boosting human capital in public administration), increased inefficiency in spending and further narrowed the ability of the state to use the budget as a policy instrument to support growth or finance social and development spending,” Hatem added.

“Elite capture” refers to a practice of politicians securing jobs or other publicly-financed benefits for supporters, who are possibly unqualified, in order to create a sense of loyalty or reciprocity.

L’Orient Today worked to untangle the nature of state spending in the immediate leadup to Lebanon’s economic crisis.

Personnel spending on the eve of crisis

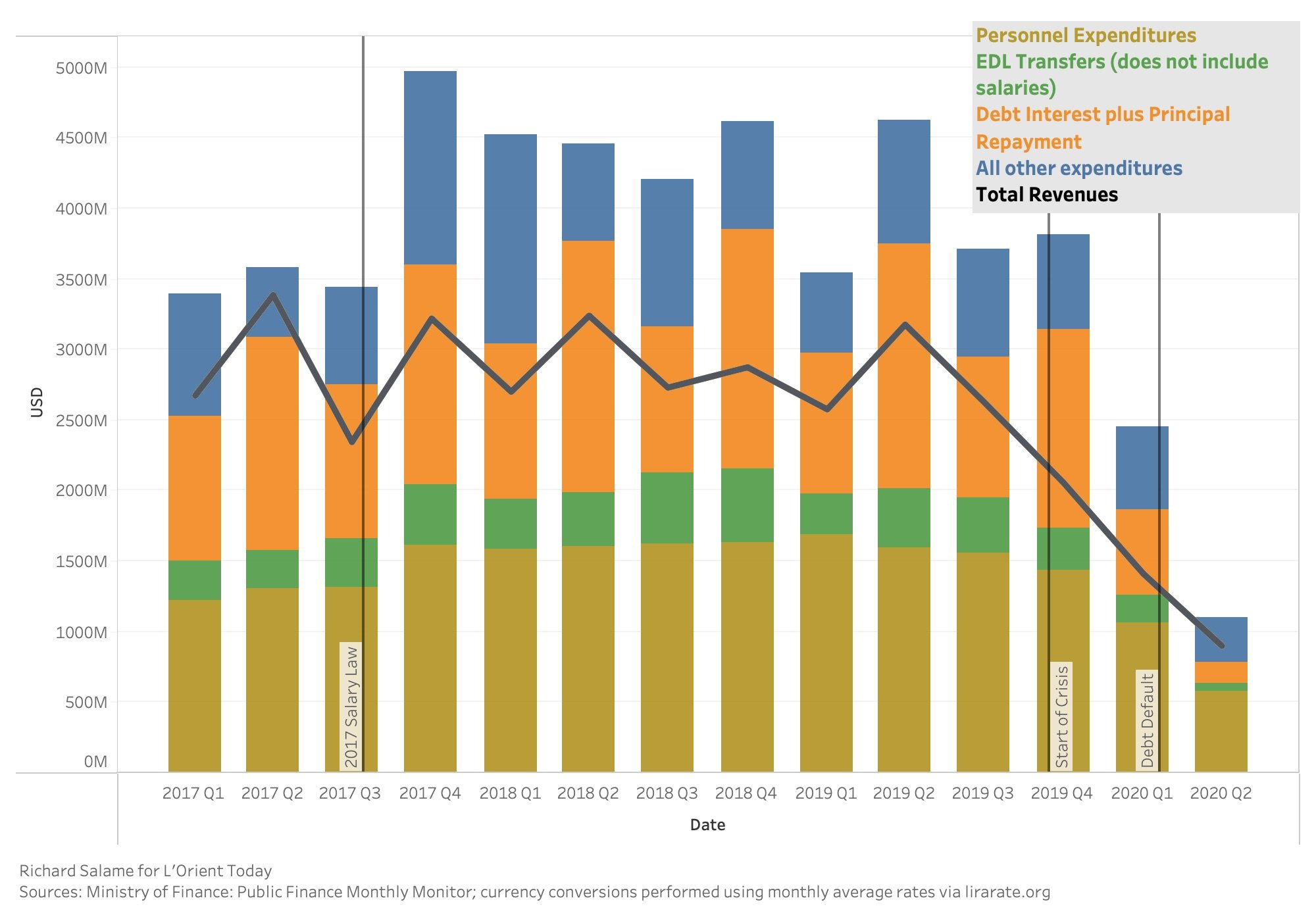

In the year before the August 2017 salary scale law, the state spent $4.87 billion on salaries and wages, retirement pensions, end of service indemnities for public sector workers, and other labor costs. By 2018, the year after the law went into effect, these costs had grown to $6.45 billion annually, a $1.58 billion (32 percent) increase.

Overall government spending jumped by $2.92 billion (19.64 percent) during that same timeframe, so part of the overall increase came from other spending categories.

Among other contributors to the increase in spending were an $830 million (89.43 percent) increase in EDL costs, attributed by the Finance Ministry (MoF) to increasing global oil prices, and a $650 million (12.99%) increase in costs associated with Lebanon’s heavy debt burden.

Greatly exacerbating Lebanon’s fiscal woes in 2018 and 2019 was a significant gap between the revenues the government expected to collect and the revenues it actually brought in.

Parliament raised taxes in fall of 2017 in order to pay for the salary increase. But in 2018, revenues fell 11.52 percent short of budget projections — a gap which grew to 16.16 percent in 2019, according to data from the Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan.

The salary law’s “sources of financing, notably from tax hikes, were overestimated,” says Hatem. “Amounts of expected VAT destined to finance the salaries did not reach their targets over the period 2018-2020.”

The cost of the salary increase was underestimated, she adds, leading to an underestimation of the state’s financing needs. In particular, pension and end-of-service indemnity costs were underestimated.

With revenues falling short of expenditure, the state continued to add to its already large debt burden in the two years immediately before the crisis, with the salary law putting finances on an “unsustainable” path, according to Hatem.

Former economy minister and central bank vice governor Nasser Saidi agrees, saying that the cost was three times greater than expected.

“As a result of that, this was debt financed at a time of high interest rates and therefore increased the overall deficit,” says Saidi.

History

The debate over the fiscal impact of the salary law has been evolving for years, but largely tended towards a negative view of its effects on the budget.

Law 46/2017 on the public sector pay raise went into effect when it was published in the official gazette on August 21, 2017. The law was accompanied by a package of tax increases (including a VAT increase and a higher rate on financial institutions) to fund the larger payments to workers and retirees, to the consternation of some private sector leaders.

The pay scale law was partly the result of five years of labor mobilization from public sector workers, including strikes and sit-ins, with workers complaining that the wages in the previous payscale, set in 1998, had been eroded by inflation. Public sector union leader Nawal Nasr previously told L’Orient Today that the 2017 law “comforted a large group” of workers.

The salary law was met with disapproval from some observers, as anxiety around government deficits were mounting amid a slowing economy.

Shortly before the law came into effect, Saidi tweeted that the move was “fiscal & monetary Hara Kiri [suicide].” In October, news site Al Monitor warned that the pay raise “could indeed precipitate the collapse of the public financial system by substantially increasing expenditures,” despite the tax increases designed to offset them.

A month after the law came into effect, the IMF raised a red flag: “The recently passed public sector salary scale increase will significantly increase fiscal expenditure .… There is an urgent need to place the economy on a sustainable path and halt the rise in public debt.”

Part of the fix, the IMF suggested, should come from improving revenue collection, which was part of the government’s plan with the fall 2017 tax law.

By December, the mood inside the MoF was somewhat optimistic about the trajectory of state finances.

“Government finances registered a notable improvement in 2017 on the back of one-off revenue and expenditure corrections, at a time when the real domestic economy continued to grow well below potential,” the MoF declared at the time.

Two months later, another IMF visit concluded that the fiscal impact of the twin 2017 laws was “expected to be broadly neutral in 2018.” A moderately encouraging sign.

But the fund warned that “higher personnel and interest costs will be main contributors to further deteriorating fiscal position” in the future.

Ten months later, in December 2018, the MoF shattered the IMF’s expectation that the moves would be “broadly neutral” that year. The MoF warned of a “significant deterioration” in government finances as a result of “subdued economic activity,” “lower-than-anticipated revenues,” and spending increases “owing mostly to the implementation of the new salary scale and to higher transfers (EDL and Municipalities).”

They concluded that the revenue law from the previous year had proved “insufficient to meet its goals in an environment of stagnant economic activity.” Revenue fell from 22 percent of GDP to 20 percent, while spending increased from 29 percent to 32 percent of GDP.

In short, revenues had been overestimated and expenses underestimated. The result was deficit spending.

Global Context

Lebanon’s wage and pensions bill wasn’t cheap before the crisis, but it was also a livelihood for the 12.4 percent of workers who were in the public sector, and their families, in a country with few ladders of social mobility.

The most recent government estimate of the size of the sector, from late May, was 250,000 workers and 120,000 pensioners, per a report produced by a special committee formed to study public sector compensation which was shared with L’Orient Today.

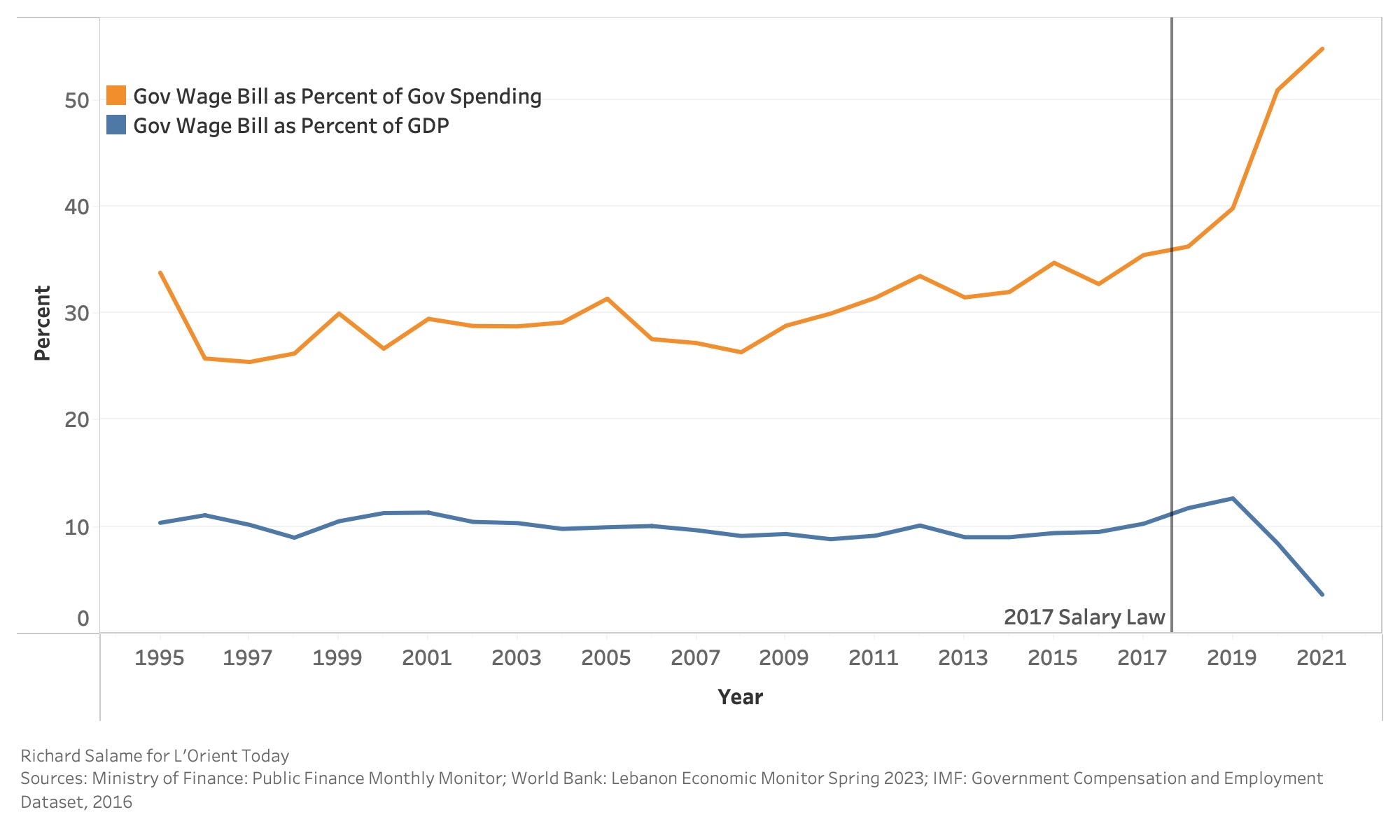

Measured against the size of each country’s respective economy, “non-advanced” economies spend an average of 7.6 percent of GDP on public sector wages, according to a 2019 IMF study.

In Lebanon, between 2015–2018, personnel costs, including benefits and pensions, ranged from 9.40 to 11.74 percent of GDP, relatively high for a “non-advanced” economy.

In GDP terms, the wage bill peaked in 2019 as GDP fell from its 2018 high. The wage bill reached 12.65 percent of GDP before falling to just 3.64 percent in 2021 as the government paid its employees in severely depreciated lira.

Measured against government spending, the pre-crisis wage bill can also be considered fairly expensive. Spending on the wage bill typically makes up “nearly 30 percent” of government spending in emerging, low income and developing countries, according to the 2019 IMF study.

In Lebanon, these costs ranged from 31.44 to 36.24 percent between 2011 and 2018.

With the crisis, government spending overall has collapsed, including the value of lira salaries and pensions. But because other spending categories have shrunk even more dramatically, the percent of spending that goes to salaries and wages has skyrocketed to 54.76 percent of 2021 spending, the most recent year for which the MoF has released data.

Today

Successive public sector pay raises have been legislated or decreed over the course of the crisis to make up for the depreciated value of workers’ lira salaries. Despite the increases, salaries remain far below pre-crisis levels.

In light of these recent moves, Saidi said that “Fiscal hara-kiri is also being committed now.”

“You have a combination of increased spending without a compensating increase in revenues and automatically that means that the deficit will rise and will be financed by the central bank. Financing by the central bank means an increase of the money supply and as a result of that increased depreciation of the exchange rate and increased inflation.”

To put a stop to what he called the “infernal cycle,” Saidi said the revenue system (such as income taxes, customs, VAT etc.) needs to be set up to automatically adjust to inflation to keep money coming in, and government reforms are needed to control spending. For instance, he estimated that 20-25 percent of public sector workers on the payroll have either died, emigrated, or stopped going to work. Removing them from the payroll would net large cost savings, he said.