Everything can now be paid in dollars in Lebanon. Where do the dollars come from? (Credit: illustrative photo/Guilhem Dorandeu)

In the midst of Lebanon’s enduring financial crisis, a perplexing phenomenon has emerged: dollar bills, available in abundance, seem to reign supreme as the universal currency. From bustling restaurants to busy super markets, every transaction can be settled in dollars it seems, replacing the stacks of depreciated Lebanese lira. This new trend has also bypassed the need for currency exchange. But where have these greenbacks come from?

“Presently, one can pay for everything directly in dollars, resulting in a significant decrease in the volume of transactions conducted on behalf of tourists or Lebanese,” said Majd Masri, head of the Syndicate of Money Changers in Lebanon.

However, recent surveys contradict this reality. The vast majority of Lebanese are not expected to have an abundance of dollars in their possession. Two surveys conducted by the German Konrad Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) and the American University of Beirut (AUB) indicated that slightly over 13 percent of Lebanese households had direct access to dollars in the first half of 2022, either through salaries or transfers from abroad. Does this figure hold true today?

Siham Rizkallah, Associate Professor at the Faculty of Economics at Saint-Joseph University (USJ), suggested that with the volume of transactions on the Banque du Liban platform (Sayrafa) and the availability of dollar conversions for public sector employees receiving salaries or pensions at the Sayrafa rate, it can be logically assumed that this proportion has increased.

Simultaneously, the notion that Lebanon is flooded with dollars is partly an illusion stemming from the accelerated circulation of currency within the economy, Rizkallah further explained.

In practical terms, this signifies that the same banknotes are changing hands more frequently , as consumers are now more inclined to directly spend the valuable bills, perceiving them as being less scarce.

This shift is attributed to an increasing number of employers opting to pay all or a portion of their employees’ salaries in foreign currency.

According to economist Albert Kostanian, “Lebanese individuals have transitioned from a mindset of hoarding to one where using dollars no longer presents as many challenges for them.”

Despite banking restrictions and the de facto devaluation of the renowned “lollars” (dollars stuck in banks), dollars already present on the market are circulating at a faster pace, which makes an increase in volume seem very real.

“But one thing is clear, more dollars are entering and circulating in the country than are being officially accounted for,” confirmed Sami Atallah, director of the Policy Initiative and author of a UNDP report on remittances to Lebanon.

To shed light on this intriguing development, L’Orient-Le Jour conducted interviews with several experts and set out to identify the potential channels through which these (seemingly) rediscovered dollars are flowing, using available statistics as a guide.

$10 billion “cash economy”

The balance of payments, which tracks all the commercial and financial transactions between Lebanon and the rest of the world, reveals a deficit of $3.2 billion in 2022 and a cumulative deficit of $15.6 billion since October 2019.

Considering the income generated from exports, tourism, and remittances from overseas, Kostanian estimates that in 2022, there remains an estimated pool of $4 to $5 billion designated for financing imports (amounting to over $19 billion). However, the source of this funding remains unestablished and raises doubts.

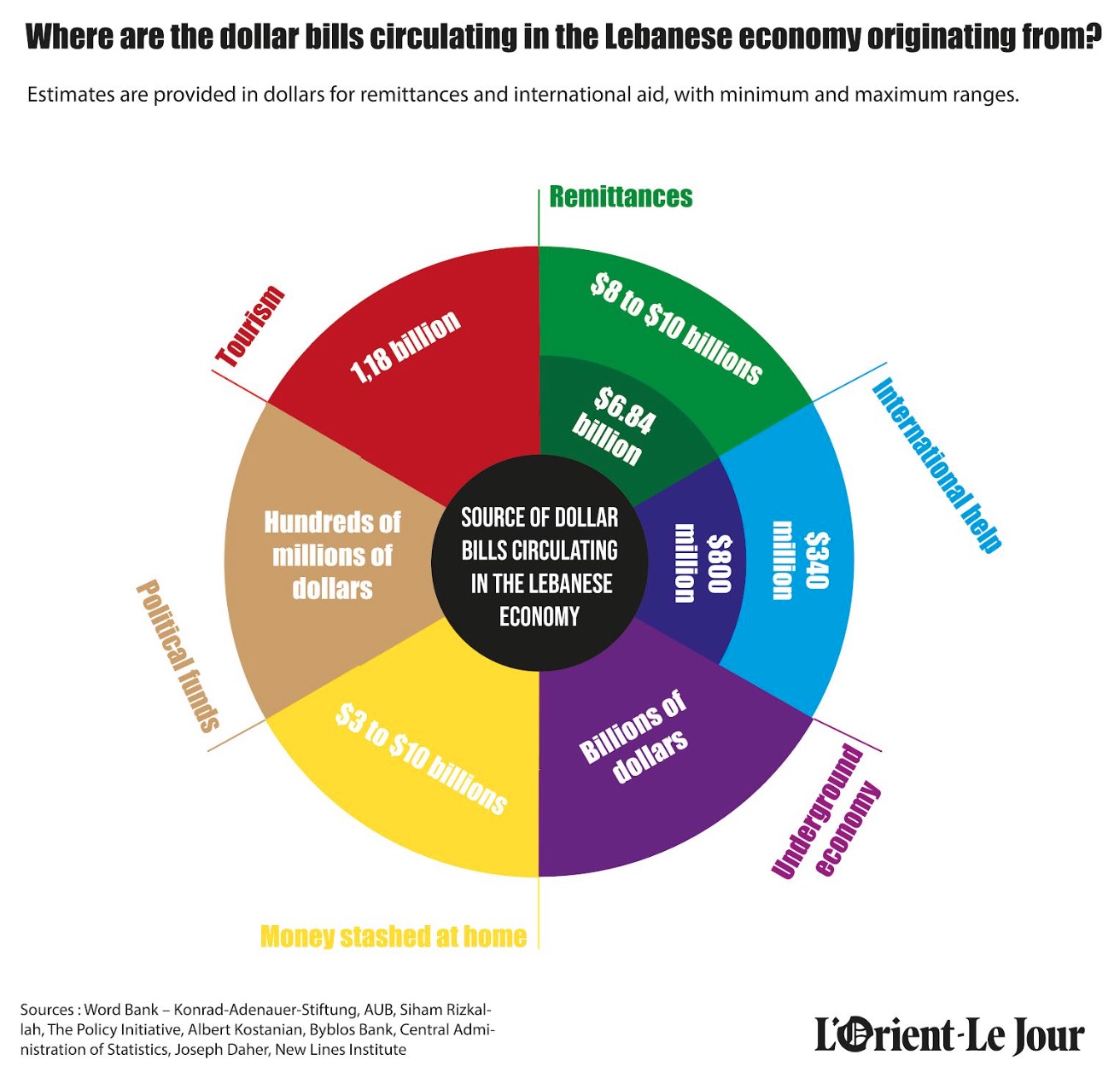

In a similar endeavor, the World Bank (WB) released a report mid-May that delved into the various sources of dollars to gauge the scale of Lebanon’s “cash economy.”

This term refers to the overall volume of dollars in circulation within the economy over the span of a year. Notably, in 2022, this estimate amounts to a significant $9.86 billion, equivalent to 45.7 percent of the country’s GDP, surpassing the figure recorded in 2021, which stood at $6.06 billion.

To arrive at this calculation, the WB takes several factors into account, including the withdrawal of foreign currency deposits facilitated through the mechanism outlined in BDL circular no. 158. Under this directive, depositors are authorized to make monthly cash withdrawals of $400 along with an equivalent sum in Lebanese lira at a fixed exchange rate, set lower than the prevailing rate in the parallel market.

According to the World Bank, this amount is expected to reach $819 million in 2022.

Additionally, the following components contribute to the overall cash economy: dollars already in circulation ($809 million); net remittances ($4.53 billion); foreign currency injected by BDL to stabilize the exchange rate on the parallel market ($2.18 billion); tourist spending ($1.18 billion); and humanitarian aid received by Lebanon ($340 million).

However, it is important to note that these figures only represent a portion of the complete picture. The World Bank has chosen not to comment on certain data that are difficult to precisely quantify, such as estimates related to cash hoarding at home or the influx of funds through official and unofficial border crossings. The authors of the report describe these aspects as highly speculative.

Regarding dollars that are still “hidden under the mattress,” or stacked away at home, there is a considerable variation in estimates. BDL Governor Riad Salamh put forward an estimate of $10 billion in 2021, a figure supported by some of the interviewed experts. However, the more conservative experts predicted a lower amount of around $3 billion.

Nassib Ghobril, the Director of the Economic Research Department at Byblos Bank, suggests that this hidden stock has decreased by approximately half since the onset of the crisis. On the other hand, Rizkallah believes that this amount has likely increased when considering all the potential sources of these savings, including withdrawn deposits, fund transfers and dollars of uncertain origin.

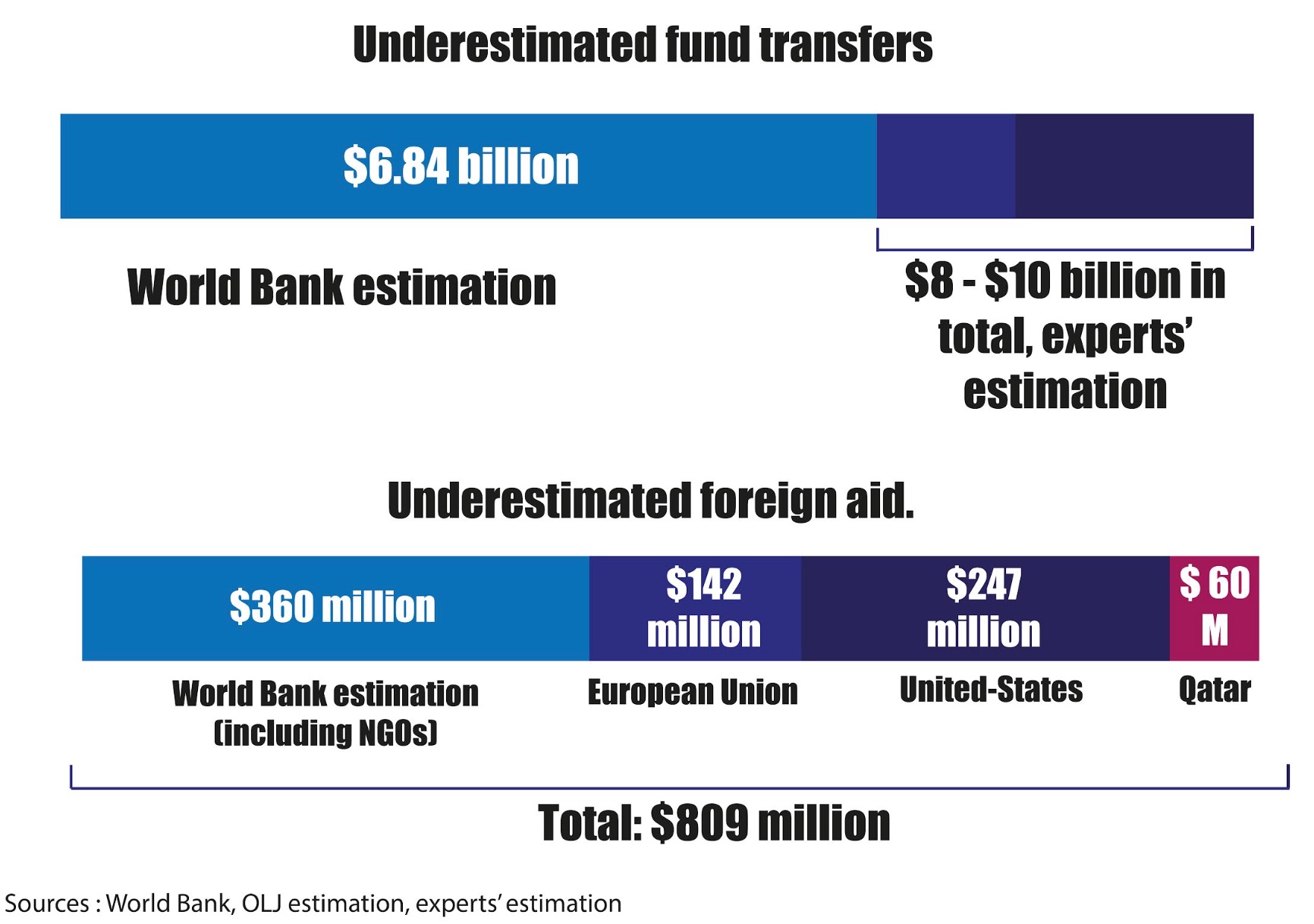

Underestimated fund transfers

Even some official figures should be approached with caution, as Atallah highlighted. He raised concerns about the accuracy of the volume of remittances from abroad, stating that the figure of $6.84 billion estimated by the World Bank does not truly reflect reality. This discrepancy is attributed to the calculation methodology and the lack of reliable data.

According to Atallah, visibility is relatively good for bank transfers from abroad and remittances sent through money transfer companies by the diaspora. However, the third channel, which involves individuals bringing dollars in cash directly in their suitcases, remains much more obscure.

“The estimation of remittances sent through these informal channels relies on a model from the 1970s, which has been updated over time but fails to consider the current reality of the country,” he said.

The crisis has significantly strengthened the informal channel, which now carries a larger proportion of remittances. According to BDL, the relative weight of this channel has increased from 39 percent in 2014 to 70 percent in 2021. The collapse of the banking sector has largely eliminated the share of bank transfers, while the portion of remittances passing through transfer companies has remained stable at around one-third.

Atallah highlighted two factors that contribute to the underestimation of remittances.

Firstly, the calculation model relies on the official ratio of Lebanese households benefiting from these remittances, which was 15 percent in 2022 according to the Central Administration of Statistics (ACS), compared to 10 percent in 2018. However, UNDP suggests that this number could be much higher, indicating a potential discrepancy.

Secondly, the model fails to consider funds sent through cryptocurrency transfers from abroad. Although this method is less costly than traditional banking or transfer companies, there is no reliable estimate available for Lebanon regarding the volume of remittances sent via cryptocurrencies.

Considering these factors, the estimates provided by the interviewed experts range from $8 to $10 billion from remittances.

In addition to the impact of remittances, Lebanon has also received significant foreign aid due to the severe impoverishment of the country. The World Bank estimates foreign aid at $340 million dollars, taking into account aid channeled through NGOs.

However, when considering additional contributions, such as 142 million euros from the European Union, over $247 million from the United States and $60 million dollars from Qatar in aid to the Lebanese army in the latter half of 2022, the total sum of foreign aid would be closer to $800 million.

Lebanon has also received an allocation of approximately $1.139 billion in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which were unblocked in September 2021.

By January 2022, two-thirds of this amount had already been utilized, primarily for purchasing fuel for Électricité du Liban (EDL) and subsidizing specific medications and wheat. Previously, these expenses were covered directly from BDL reserves.

Underground economy

While these various sources can be more or less measured, the amounts stemming from illegal activities are even more challenging to quantify. Specifically, when it comes to the flow of illicit funds through official or unofficial border posts. As was previously mentioned by the World Bank, there are multiple avenues to consider.

One such avenue involves money generated from smuggling and drug trafficking. According to researcher Joseph Daher, author of the book “Hezbollah: un fondamentalisme religieux à l'épreuve du néolibéralisme,” (Hezbollah: religious fundamentalism put to the test by neoliberalism), this money is derived in part from the numerous border crossings between Lebanon and Syria, estimated to be around 120 to 150. The majority of these crossings are illegal, with a significant portion under Hezbollah’s control.

Caroline Rose, a researcher at the New Lines Institute, shed light on the scale of captagon trafficking, estimated to be valued at around $5.8 billion annually. Even with conservative estimates, this illicit trade generates profits ranging from $2.5 to $3 billion, which are divided between Syria and Lebanon.

However, determining the distribution of these profits and their specific economic impact on Lebanon presents an even greater challenge. Rose emphasizes that unraveling these intricacies is a complex task, further highlighting the difficulties associated with illicit activities and their ramifications on the Lebanese economy.

Apart from illicit activities, there is the dimension of political funding sent from abroad to various Lebanese parties, which is also difficult to quantify. Estimates have been suggested for Hezbollah, one of the main parties in question. Hanin Ghaddar, a researcher at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, saidHezbollah received between $300 and $400 million from Tehran in 2022.

Ghaddar recently co-authored a report highlighting the profits accumulated by Hezbollah through the expansion of the “cash economy” in Lebanon.

This cash-driven economy has established its own set of rules and is expected to persist, even in the face of monetary deterioration. It facilitates the continuous circulation of dollars, whether illusory or not, and maintains its momentum within the Lebanese economic landscape.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.