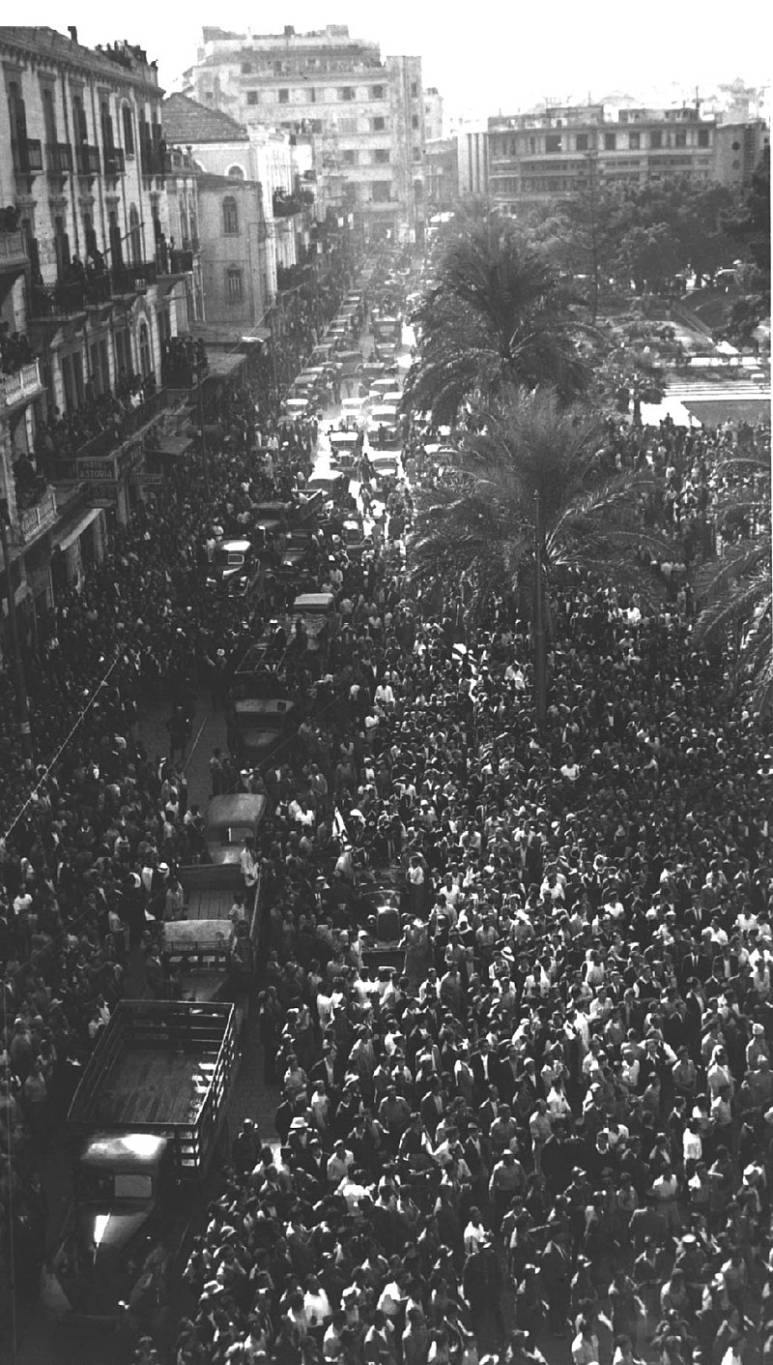

Martyr's Square in downtown Beirut during the country's first Independence Day celebration on Nov. 22, 1943. (Credit: Wikimedia commons)

BEIRUT — The carefully choreographed protocol for Lebanon’s official Independence Day events envision a government headed by a president, a prime minister and a speaker of Parliament. Twenty-five wreaths are laid on statues, tombs and locations of assassinations, with the wreath-laying duties assigned to state officials in advance by the offices of the three “presidents.”

Then, the three presidents gather, with the minister of defense and top army officers, for a ceremony and military parade. If an incoming prime minister-designate has not yet taken over from an outgoing caretaker prime minister, both attend and stand at the president’s left.

Currently, one man, Najib Mikati, is both the caretaker prime minister of the outgoing cabinet and the prime minister-designate of the unborn, future cabinet.

But, this year, with a presidential vacancy, the military parade will not be held, according to remarks given by the Director General of Protocol at Baabda Palace, Nabil Shadid, to the Nida al-Watan newspaper. An army spokesperson confirmed to L’Orient Today on Monday there would be no parade.

This continues a streak of scaled-down celebrations. Last year the government held a reduced version of the parade in Yarze due to the economic crisis and the COVID pandemic. No parade was held in 2020 for the same reasons. The previous year also featured a minimal event at Yarze, overshadowed by the country’s first-ever civilian independence day parade, courtesy of the protesters who had descended on Martyr’s Square the previous month.

Presidential vacancies have caused the government to cancel Independence Day parades before — in 2014 and 2015, for instance. But the current so-called “double executive vacancy” of both the premiership and presidency have been considered a particularly ill omen.

The vacancy was, however, hardly a surprise as President Michel Aoun’s term came to a close with no majority choice in Parliament, let alone consensus among parties, on a successor.

Mikati, meanwhile, was designated to form his fourth cabinet in June. He has yet to do so. His previous cabinet,which resigned in May following parliamentary elections, had lasted 244 days, following a vacancy of 406 days. It is now serving in a caretaker capacity, with limited powers.

Lebanon’s repeated inability to form cabinets in the period following Syrian withdrawal in 2005 is well known, but it wasn’t always so hard to form a government.

Independence to Civil War

The cabinet that is considered to be independent Lebanon’s first was in fact elected two months before the day now commemorated as independence day.

On Sept. 25, 1943 Riad Solh was designated Prime Minister by President Bechara El Khoury. Both Solh and Khoury would later be arrested alongside other political leaders by the French mandate authorities in a bid to prevent Lebanese independence — which the Lebanese had unilaterally declared. The release of Lebanon’s politicians on Nov. 22 as a result of popular pressure would be marked as Lebanese Independence Day. Solh’s inaugural cabinet would go on to serve 270 days in total.

Since independence Lebanon has enjoyed — or suffered, based on one’s perspective — 77 cabinets. Nine of them never came before Parliament for a vote of confidence, meaning they never took on the full powers of the cabinet. For the rest, they were sometimes short-lived affairs: six cabinets were fully empowered for fewer than 100 days. On average, each one has lasted just over a year in office.The period from independence to the start of the Civil War, usually dated to the April 13, 1975 Ain al-Rummaneh bus massacre, saw 49 governments formed in just 32 years, averaging fewer than nine months per cabinet.Cabinets came and went at speed. The month of September 1952 saw four separate cabinets formed one after another.

But there were stretches where a single prime minister would remain from cabinet to cabinet. After a brief interregnum following his first two cabinets, Riad Solh returned to form four cabinets back-to-back in the late 1940s.

Rashid Karami was designated prime minister eight times in the pre-war period, often trading control of the cabinet back and forth with Abdallah el-Yafi who formed nine cabinets during the same time period. If the cabinets were fragile, the prime ministers who headed them proved far more resilient.

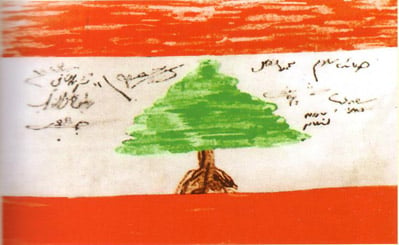

The first hand-drawn Lebanese flag, from 1943. (Credit: Wikimedia commons)

The first hand-drawn Lebanese flag, from 1943. (Credit: Wikimedia commons)

And the Lebanese political class proved adept at preventing vacuums. Despite seven cabinets failing to achieve Parliament’s confidence in this time period, the average vacancy between fully-empowered governments was 18 days, or 732 total days of cabinet vacancy in 32 years — six percent of the total time period.

Civil War

The Civil War saw nine cabinets come and go. At the beginning of the war, ISF chief Nureddin Rifai was designated to form a government a month after the Ain al-Rummaneh massacre, following Rachid Solh’s cabinet’s resignation. After just 39 days he threw in the towel.

The subsequent governments, on the other hand, were eerily long-standing, as formal political life largely took a back seat to the power struggles among and between local militias and foreign armies.

The Karami government, formed in July 1975, lasted for a well-above-average 513 days from confidence to resignation and was followed by Selim Hoss’s first cabinet, which served for 934 days. Three more governments came and went with more than a year in service each, culminating in Lebanon’s longest-serving cabinet ever: the 1984 Karami government. It ran for 1,575 days, outliving its own prime minister, who was assassinated in 1987 and replaced by Hoss.

In the late 1980s things got famously messy. In the final minutes of his presidential term, in Sept. 1988, then-President Amine Gemayel dismissed acting Prime Minister Selim Hoss and appointed in his stead Michel Aoun. Hoss had been acting Prime Minister since Rachid Karami’s assassination the previous June.

Hoss refused to accept his dismissal or Aoun’s appointment and continued as a disputed prime minister based in West Beirut. Aoun took office as a second disputed prime minister based in Baabda, without Parliament’s confidence.

With no presidential replacement for Amine Gemayel until November of the following year, Hoss and Aoun both claimed the powers of the presidency as well as the premiership.

But Aoun lacked a vote of confidence while Hoss lacked both a presidential designation and a vote of confidence, meaning the cabinets were not legally fully empowered, to say nothing of the state’s actual authority amid the civil war. With the presidency also vacant between Sept. 1988 and Nov. 1989, Lebanon faced, like today, a “double vacancy.”

With René Moawad’s election to the presidency in November 1989, Hoss resigned. Moawad was promptly assassinated and Elias Hrawi was elected his successor. Hrawi immediately declared that the Aoun cabinet was considered to be resigned and designated Hoss to form a cabinet, which gained confidence just one day later. This confidence capped off what was, and remains, Lebanon’s longest de jure prime ministerial vacancy of 430 days.

Aoun stuck it out 11 more months before being forced out of Baabda Palace by the Syrian Army in Oct. 1990. The Hoss government would outlast the famously stubborn Aoun by just two months before resigning.

Despite all this, the cabinet was vacant for just 11 percent of the civil war era.

The second republic

Under the so-called Pax Syriana of 1990–2005, Lebanon’s cabinet formation process became a choreographed affair. It was also more important for overall political life than it had been previously, since the Taef Accord had transferred a number of executive powers from the president to the cabinet.

Cabinets were formed on the same date as previous cabinets’ resignations, and the gaps without a fully-empowered cabinet averaged just 13 days, with Parliament convening to grant confidence quickly for a legislature that is not often known for its speed.

It was after the Syrian withdrawal in 2005 that Lebanon entered its current predicament. Namely, the country appears incapable of efficiently forming cabinets.

Since the Syrian withdrawal on April 30, 2005, Lebanon has been in a cabinet vacancy 29 percent of the time, a rate that seems likely to keep ticking upwards as the current cabinet vacancy drags on. It’s a rate much higher than that of the pre-war period, and even that of the civil war.

Lebanon has formed nine governments post-Syrian withdrawal with an average of 185 days of vacancy between each one. By that yardstick, the current 184 days since Mikati’s June designation to form his fourth cabinet is average, although he shows no sign of forming a cabinet any time soon — let alone presenting it to Parliament for confidence.