The statue of Saint Elijah in the main square of Qaa. (Credit: Matthieu Karam)

Qaa is a small town, one of those arid-looking Baalbeck-Hermel villages that have nothing special about them, wedged between two mountain ranges where life is harsh, and enjoyment is rare.

Lying at a few kilometers from neighboring Syria, the town paid a heavy price for the war raging next-door, witnessing a massive refugee influx, a corridor for drug smuggling and trafficking, and suicide bombings.

Six years after making headlines with the suicide attacks of June 27, 2016, the town has now been shaken up by another horrific story, the kind of story that many prefer to keep hidden under the rug.

On July 5, the local media reported that a man in his 50s, suspected of several rapes and sexual assaults against minors, was arrested by the army’s intelligence branch.

The Saint Elie church on the main square of the village of Qaa. (Credit: Matthieu Karam)

The Saint Elie church on the main square of the village of Qaa. (Credit: Matthieu Karam)

It was not long before the story turned into a bad novel of rumors and talk of political vengeance, putting a black mark on the small town.

The local media went into a frenzy, feeding off of social networks posts, revealing the name of the accused, and frantically reporting on the incident seemingly without any fact-checking.

Reports spoke of this “pedophile monster of Qaa,” the “wolf” who assaulted 20 children, maybe more, including young Lebanese and Syrians, men and women, spiking their juices or shishas to lure them.

In a country where politicians are constantly trying to elbow their way past each other, they began trading accusations of who was providing cover to the culprit to hush up the story.

Between the media scoops and political dirty tricks, the reality is often a gray area.

The village’s alleys with their small two-storey houses were empty except for passing tractors and mopeds. Not a child in the streets.

Qaa’s townspeople seem to have hunkered down in their homes. For the past 10 days, “it” has been the talk of the town. The news has spread like wildfire.

In a few days, the village’s main square would be full of people for the celebration of Saint Elias’ day, the town’s patron saint.

On the main roundabout, an imposing statue of the saint with an index finger pointing to the sky inspires both fear and respect.

Back on June 27, 2016, the head of a suicide bomber who had blown himself up was found at the statue’s feet. On that horrifying night, the villagers woke up in terror to the sound of a simultaneous jihadist attack, which cost the lives of five people and injured more than 30.

Since this fateful night, the inhabitants and the army are constantly on the alert. Things do not seem to have gone back to normal ever since.

Antoine*, a soldier in the army intelligence, showed up in plain clothes in his four-by-four, abruptly requesting L’Orient-Le Jour’s reporters to show their press cards, inquiring about the nature of photographs they were taking in the village.

He “never sleeps,” he said, priding himself on having recently arrested a drug bigwig, and insisting on the serious threat of kidnapping in the area.

The Greek Catholic priest of the parish of Qaa, Father Elian Nasrallah. (Credit: Matthieu Karam)

The Greek Catholic priest of the parish of Qaa, Father Elian Nasrallah. (Credit: Matthieu Karam)

Paranoia in the village

In 2016, the whole country was moved by the attacks that hit this remote Christian village in the Bekaa.

But today, this story has brought disgrace to the town. Pedophilia, which is wrongly linked to homosexuality, is an extremely taboo subject within the village’s society.

“It’s a very hard blow because the enemy is not external this time, he lived within the community,” Bachir Matar, the town’s mayor, told L’Orient-Le Jour.

Sitting behind his small desk cluttered with files, he spoke firmly without mincing his words.

He criticized the media and the politicians for engaging in one-upmanship, sowing panic among families.

He added that he “has faith in the judiciary,” which should be given “the opportunity to do its work far from controversies.”

“We have read and heard everything and its exact opposite. E.D. — the alleged perpetrator — is a man from the village whom everyone knows. He comes from a well-liked family, and he must be tried like any other citizen for the crimes he committed,” Bachir Matar said.

“Whether there was one victim or 20, this doesn’t take away from the seriousness of the case. A child is sacred,” he added.

When the arrest was leaked on social networks in early July, paranoia spread among families, and parents began to interrogate their children compulsively, bombarding them with questions: “Did this guy do something to you?” “Did you go to drink a Nescafe at his place or smoke shisha?” “Did he make you watch porn videos?”

The president of the municipality of Qaa, Bachir Matar. (Credit: Matthieu Karam)

The president of the municipality of Qaa, Bachir Matar. (Credit: Matthieu Karam)

In 2013, the accused, whom the young people of the village nicknamed the “Khal” (uncle), came back to live in the town. It was the year he ended his service in the army. He settled down in the family house on the edge of the soccer field.

Idleness is the mother of all vices — people say today in the streets of Qaa.

There are no “fags here,” others are heard saying. Some blame it on the Syrian refugees who are “too many,” and “whose morals are far from the Christian tradition."

“People were livid. That’s for sure. And if he hadn’t been arrested, some people would not have hesitated to kill him,” Bachir Matar said.

Since his return to Qaa, some people have taken a dim view of the way E.D., a bachelor in his 50s who hung out with young teenagers.

Tony Matar, a journalist and professor at the Lebanese University, even went to confront him a decade ago.

“I told him to stay away from my four sons. I had doubts about his intentions. But I didn’t have any concrete proof for an arrest to be made,” he told L’Orient-Le Jour.

“But a part of me, I admit, did not say anything, only to protect my children,” the professor added.

Recently, the mukhabarat, the army intelligence service, got suspicious of him and placed him under surveillance.

One of the alleged victims reportedly confessed to her family that E.D assaulted her, prompting them to file a complaint, which led to his arrest.

The army retiree allegedly confessed to his crime.

“He is a very intelligent person who did not force his victims but, on the contrary, established a climate of trust, and knew how to take advantage of the lack of supervision by the parents to have these teenagers come to his home,” said Jean*, a municipal employee.

The defendant’s cell phone was sifted through, including his photos, his videos, and his contacts.

“My children's numbers were there,” Tony Matar said.

Very quickly, alleged photos of E.D. began to circulate on the internet. A municipal employee in the town, with the same name, saw his own photo making the rounds on social media. He had to write a post on his Facebook page denying any connection to the accused. “All this gossip has caused a lot of damage to the village,” the mayor said.

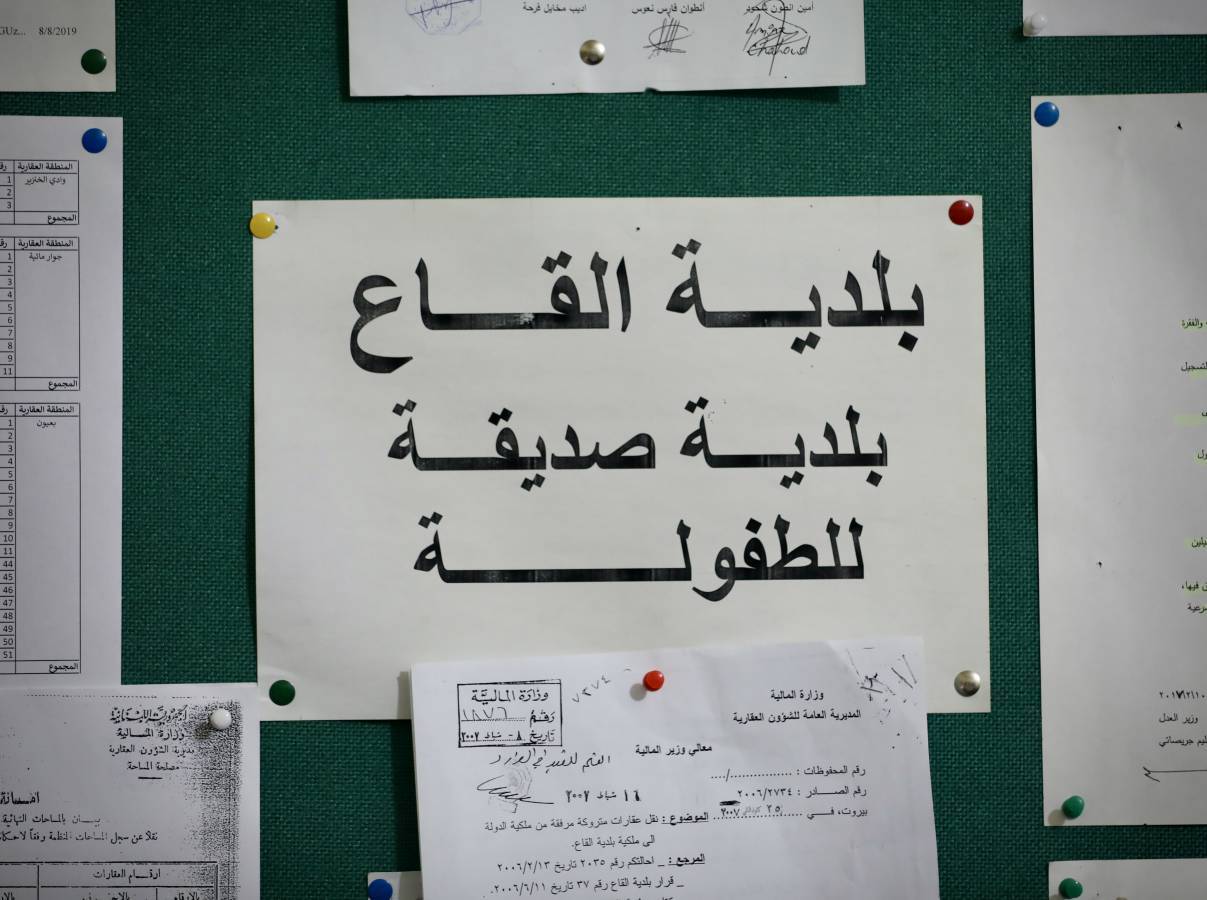

A billboard in the mayor's office where it is written: “The municipality of Qaa is the friend of young people." (Credit: Matthieu Karam)

A billboard in the mayor's office where it is written: “The municipality of Qaa is the friend of young people." (Credit: Matthieu Karam)

Revealing themselves before the authorities

At the beginning, some sources claimed that he was protected by the Free Patriotic Movement.

“Nonsense,” said Bachir Matar, who is affiliated with the Lebanese Forces.

Cynthia Zararir, an MP from the protest movement, accused “political parties, clerics and activists, as well as MP Samer el-Tom (FPM/Baalbeck-Hermel) of hushing up the story.”

Tom denied these accusations in a statement.

“Nobody protected him, he is a regular guy, not a senior politician suspected of being involved in the Beirut port explosion as far as I know,” Bachir Matar said.

According to several police and judicial sources, five Lebanese boys aged between 15 and 17 have so far filed complaints, but there could be other victims. For fear of being stigmatized or for fear that their identity could be revealed, some of the victims’ families weren't ready to come forward to the authorities.

On the fifth floor of the Justice Place in Zahle, where there was no electricity in the early morning, Malak Kassem, a social worker from the Union for the Protection of Juveniles in Lebanon (UPEL), told L’Orient Le-Jour that she met separately with the five victims in a room recently rehabilitated by UNICEF to welcome minors.

“Teenagers have a harder time than children confiding [to adults] because they know that things have consequences. There is the fear of being rejected and the feeling of shame that comes into play, especially when the public opinion is informed,” she explained

The investigation was entrusted to the Bekaa’s first investigating judge, Amani Salameh.

According to UPEL President Amira Sukkar, the children will be subject to further psychological follow-up because of the nature of these crimes “which take a long time to recover from.”

“Today we are in pain, but we must re-examine ourselves, because this story has proven that none of us was trustworthy enough in the eyes of these children to come and talk to us about it,” said the mayor, adding that he has big dreams for his deprived village.

Father Elian Nasrallah, a Greek-Catholic priest of Qaa, who also runs a medical dispensary and a charitable association, weighed his words as he talked about the topic that “breaks his heart.”

He receives people in civilian clothes in a classroom full of books and music instruments. He too was accused of having sought to settle the issue quietly between village notables — an allegation that he denies.

“The mayor came to tell me about it during the end-of-the-year school celebration. We were all shocked and organized a meeting among ourselves the next day to talk about it, but we never tried to protect the criminal, we just wanted to protect the identity of the victims,” he said.

“Qaa is the Lebanese Army’s reservoir. Just because one of its members strayed from the right path does not mean that the whole army should be incriminated,” he added.

As he sipped his coffee, Abouna (father) Elian assured L’Orient-Le Jour that children never complained to him about E.D.

Amid all this confusion, some parents decided not to send their children to the summer camp organized by the parish.

Perhaps when another new story hits the headlines, people will eventually begin to talk.

* First names have been changed.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.