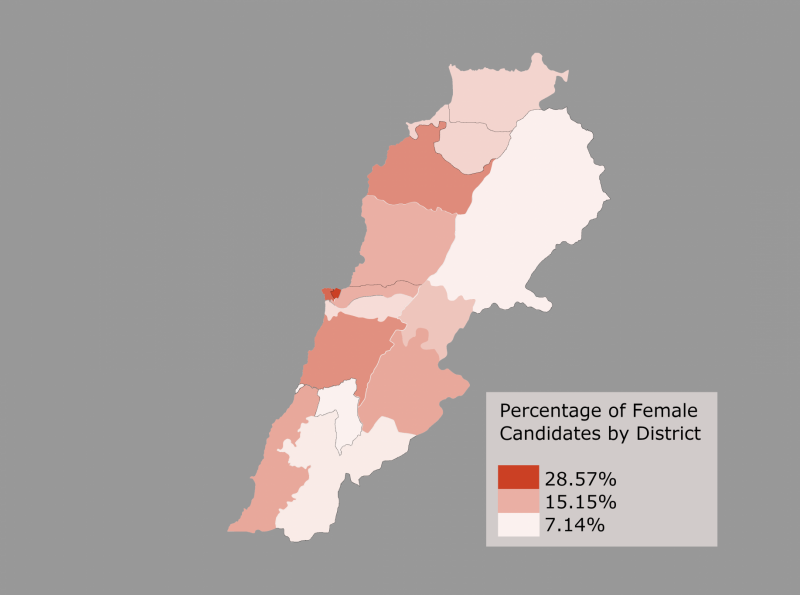

A map showing the distribution of women candidates by district in Lebanon. (Credit: Richard Salame)

BEIRUT — When the March 15 filing deadline for candidates to register in May's parliamentary elections had passed, 157 women* had signed up to run making up some 15 percent of the 1,043 total candidates, compared to 11 percent in the 2018 polls.

They included both new and old faces, members of establishment political parties and of a range of opposition groups.

Who are they, where are they running, and what are their chances of making it to the halls of Parliament?

Where are the most women running and why?

The number of women running varies across Lebanon, with the highest concentration of candidates being in Beirut. Women candidates are most represented in Beirut I, where they make up 29 percent of parliamentary hopefuls. The only other district where women make up more than 20 percent of candidates is Beirut II, at 24 percent. In nine districts they are between 10 and 20 percent of candidates. In four districts they are less than 10 percent of candidates.

Women are least represented in Baalbek-Hermel and Saida-Jezzine, where they make up 7 percent of candidates each.

On a sectarian basis, the proportion of women candidates is highest among Evangelicals, where they comprise four out of the 11 Evangelical candidates, or 36 percent. Women make up 29 percent of Armenian Orthodox candidates, 25 percent of Armenian Catholic candidates, and 20 percent of Druze and Christian minority candidates. Among Maronites, women make up 16 percent.

Among Shia and Sunni candidates, they make up 13 and 12 percent, respectively. The sect with the lowest proportion of female candidates is the Alawite sect, with 9 percent.

Feminist activist and former Vice President of the National Comission for Lebanese Women, Abir Chebaro and Myriam Sfeir, director of the Arab Institute for Women at the Lebanese American University told L'Orient Today that the difference in percentage among districts and sects likely has historic roots .

The more welcoming a certain environment is for women politicians and decision-makers, they said, the more encouraged women would be to run for office or parliament in that area.

In addition, “the more women's involvement was welcomed in [politics] over time, the more encouraged women from these sects would be to participate in politics,” said Chebaro.

The experts noted that Shiite women, for instance, are more likely to run as independents than with established political parties, because the main Shiite parties field female candidates rarely, in the case of Amal and never, in the case of Hezbollah.

While other establishment parties may run more women on their lists, that does not necessarily mean they have meaningful participation, the analysts added.

“Traditional political parties are trying to play the gender card,” Sfeir said. These parties generally do not have active women leaders but rather relegate their female members to women's committees, she added, noting that some of the new emerging political groups are exceptions and are “trying to include gender equality narratives and incorporate gender principles in their manifestos. ”

Chebaro agreed that establishment parties often include women on their lists for mere “gender washing” or branding.

“Some women are hosted in traditional lists with little to none responsibilities besides going to events, taking some pictures and clapping on mothers day,” said Chebaro.

Two of the most important parliament committees, the Finance and Budget Committee, responsible for legislating the annual budget plans including ministerial budget plan and taxation along with the Administration and Justice Committee, which discusses proposals that establish controls on bank transfers, do not include any women parliamentarians.

Who are the women running?

In the 2018 elections, only six women were able to secure parliament seats: Paula Yaacoubian, Sethrida Geagea, Inaya Ezzeddine, Rola Tabsh, Bahia Hariri and Dima Jamali. Of those, Tabsh, and Hariri, who are members of the Future Movement, have followed party leader Saad Hariri's boycott of the elections this year; while Jamali, who is also with the Future Movement, suspended her role in the parliament in Oct. 2020 when she moved to the United Arab Emirates for a job.

Of the three who are seeking re-elections, Yaacoubian, a former journalist running on Tahalof Watani opposition list, was the only independent candidate to win a seat in the 2018 Lebanese parliamentary elections, when she ran with Sabaa party for the Armenian Orthodox seat in the Beirut I constituency; Ezzeddine, is a doctor and former minister who has represented the Amal Movement in Sour since 2018 (she was the first woman candidate to be put forward by the party) and currently chairs the Women and Children Parliamentary Committee; Geagea is the wife of Lebanese Forces head Samir Geagea and has been occupying a Maronite seat in Bsharri since 2005.

Like Geagea, a number of the other women candidates running have family ties with prominent men in the political scene.

For instance, Myriam Skaff, who is running for the Greek Catholic seat in Bekaa I, Zahle, is the daughter of former MP Gebran Tawk, was elected head of the Popular Bloc after the death of her husband and head of party Elias Skaff in 2015 She had previously run in the Zahle municipal elections, which she lost. She also lost in the 2018 parliament elections, when she ran for a Catholic seat in Zahle on her own list.

However, others are newcomers to the scene. Among them is Verena el Amil, the youngest candidate at 25 years of age, who was active on the streets during the Oct. 17, 2019 protests. She graduated with an MA degree in business law at Saint Joseph University and comparative law at Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and is a member of the Beirut Bar Association. In 2018, she worked on Gilbert Doumit's campaign, a candidate for the last parliament elections in Beirut I with Li Baladi, a civil society group. In 2017, she founded the Taleb' movement in USJ as a political alternative, which won eight out of 13 seats in the law school's student elections.

A random sampling of other female candidates running outside of the established political parties include:

Running for the Greek Catholic seat in Beirut I, is visual artist Nada Sehnaoui, a founding member of the Civil Center for National Initiative, which campaigned to remove the sect category from state records and aimed to administer civil marriages in Lebanon. She ran for municipal elections twice in Beirut, the last time in 2016 on a list established by the independent party Beirut Madinati. However, she did not win.

Nihad Yazbek, head of the Syndicate of Nurses. She has held several academic and administrative positions at AUB and worked as a consultant for several projects in higher education in Lebanon and the region. She is currently running for the Evangelical seat in Beirut II with Beirut Tuqawem, an independent group.

Magguie Mhanna is running for the first time for the Druze seat in West Bekaa-Rashaya on the Qadreen list of the Citizens in a State (MMFD) opposition party. She holds an MA in computer systems networking and telecommunication from the Lebanese University and another MA in renewable energy science and technology from École Polytechnique in France, along with a PhD in information and communication technologies and sciences from CentraleSupélec. She currently works as a cloud solution architect and data scientist at Microsoft and is a machine learning instructor.

Josephine Zgheib is running for the Maronite seat in Keserwen, also with MMFD. She was a parliamentary candidate in the 2018 elections with Kulluna Watani and has been a member of the city council of Kfardebian since 2010. She founded the Beity association and Auberge Beity, a hostel for youth and an incubator for activities in social development and rural tourism . She is the vice president of the Arab Affiliated Network for Social Accountability, a network of activists from seven MENA countries funded by the World Bank.

Halime el-Kaakour, running for a Sunni seat in Chouf with Tahalof Watani, of which she is a cofounder, has a Ph.D. in international law and human rights. She lectures in the faculty of law and political science at the Lebanese University and is a researcher in local development issues, governance and gender equality. She previously ran unsuccessfully for office and is the author of a UN Women report entitled “Pursuing Equality in Rights and Representation: Women's Experiences Running for Parliament in Lebanon's 2018 Elections.''

Layal Bou Moussa, an investigative reporter with Al Jadeed TV, who is running for a Maronite seat in Batroun with Shamalouna, a political coalition formed by the people in Bcharre, Zgharta, Koura and Batroun. In addition to her work as a journalist, Bou Moussa has worked as a consultant for local and international organizations on the investigation of the Beirut port blast, and the fight against corruption.

Here is the full list of women candidates:

What are the obstacles for women candidates?

Although Lebanon's electoral law follows a proportional representation model, which in general is considered to enable minority groups to win seats, some argue that the configuration of the current law creates a barrier for women. Because Lebanon's proportional electoral system also includes sectarian quotas and preferential votes for individual candidates, women do not only compete with people on other lists but also with the candidates in their own lists.

When women run through electoral lists, one female candidate who wins a lot of votes but happens to be on a failing electoral list would de facto fail. And a winning list whose female candidates did not receive preferential votes for women could win without its women getting seats.

Furthermore, if women candidates do not form alliances and make it onto electoral lists by April 4, they will have to drop out from the elections, given that lists are obligatory in the electoral law.

“Women registered their candidacy for the legislative elections, but are they all endorsed in lists?” asked Sfeir.

When the number of seats allocated by quota for a certain sect in parliament are few in certain districts, the allotted seats are likely to go to men and not women thus disencouraging women to run, she added.

Traditional parties tend to nominate women who are public figures with social reach and almost never nominate women who are rank and file party members or have political experience, which is an example of gender washing, Chebaro said.

“And when people do not trust the credibility of such women in decision making and in politics they will tend not to give them their preferential votes,” she added.

There are other obstacles that could prevent women candidates from reaching seats in the parliament.

There is a financial obstacle for candidates, who had to pay LL30,000,000 to register. This could be harder for women candidates given that they are paid less than men, on average, in Lebanon. They must also pay for their campaigns, competing with other candidates who might bribe voters with money or services, said Joelle Abou Farhat the co-founder and CEO of FiftyFifty, an NGO that promotes gender equality in the private and public sectors.

“And members of the Lebanese society are not brought up to consider gender equality as a priority [so] during a socio-economic crisis, people's criteria will be based on who can grant them their basic needs as opposed to voting for a candidate to bring equality,” said Chebaro.

Without a women's quota, she added, “I do not expect more than six women to be elected." Even the Supervisory Commission for Elections, which the law stipulates should have equal numbers men and women in it, has only two women out of 11 members.

And even if the number of women MPs does increase, Abou Farhat noted that it will not necessarily lead to a change in laws affecting women's rights.

“We also need to eliminate laws that are unfair for women and the only way to achieve that is through having 40 women MPs, because no law can be passed without a vote from one third of the parliament,” she said.

However, the experts noted that women's representation in countries with more gender equality was not achieved out of the blue, but was preceded by affirmative measures and buy-in from the society.

“I personally think that change is happening. Women who ideally will get there [to the parliament] will be holders of feminist agendas, and even men from non-traditional poitical groups. But to be honest, because of the economic crisis, people will accept snippets in exchange for their vote. This will be a determinant on whether people will vote for women or not,” said Sfeir. “I doubt we will have a huge female representation in the parliament.”

*While the Interior Ministry initially said the number was 155, the final list showed 157 female candidates

This article has been updated to clarify the number of women required on the Supervisory Commission for Elections.