Electoral agents from the CENI, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, recount the votes during the 2011 elections. (Credit: Simon Maina/AFP)

In 2011, the Lebanese company Inkript Industries was awarded a contract to supply the Democratic Republic of the Congo with electoral materials intended for the presidential elections. However, the Congo Hold-Up investigations pointed to multiple irregularities that tainted these elections. The investigations, which are based on the largest financial information leak in Africa, enabled access to the accounts of the entity in charge of organizing the polling, the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), and revealed issues that raise questions about the contract awarded to Inkript.

Resource Group Holding (RGH) presents itself as the best-of-the-best of Lebanese companies in the new tech industry. It achieved an “annual business revenues of more than $200 million, with 14 offices in the Middle East and in Africa and more than 2,000 employees,” RGH’s founder, Hisham Itani, told Le Commerce du Levant in 2018.

The son of former MP Mohammad al-Amin Itani, who belonged to the Future Movement’s parliamentary bloc, was named as one of the top 35 most influential Lebanese businessmen by Forbes Middle East in 2018.

Inkript, a subsidiary of RGH, has received recognition in the past. Founded in Lebanon in 1973, the digital security company grew with the market and was awarded numerous contracts. In Lebanon, it served as the official supplier of fiscal stamps to the Finance Ministry for 11 years, from 1998 to 2019, and was awarded a contract to manufacture new biometric passports in 2015.

However, Inkript’s activities in Africa made it the subject of scrutiny. For instance, Africard Co. RCA, a subsidiary of Inkript, was under suspicion in 2014 of manufacturing bogus passports as part of a contract signed in 2010 under François Bozizé, the former president of the Central African Republic.

Speaking with L’Orient-Le Jour and its partners in the Congo Hold-Up consortium, Inkript said it was not implicated either directly or indirectly “in any illegal activity, whether in the CAR or any other country.” It added that passports in the CAR are manufactured “under the supervision of the competent … authorities’ and to their full satisfaction.”

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Inkript was a party to one of the biggest contracts associated with the presidential elections on Nov. 28, 2011, which pitted Joseph Kabila against Etienne Tshisekedi, the current president’s father, and resulted in Kaliba’s triumph.

The contract, which was awarded in June of that year, focused on supplying electoral materials, including voting booths and electoral kits for polling stations and vote tallying centers.

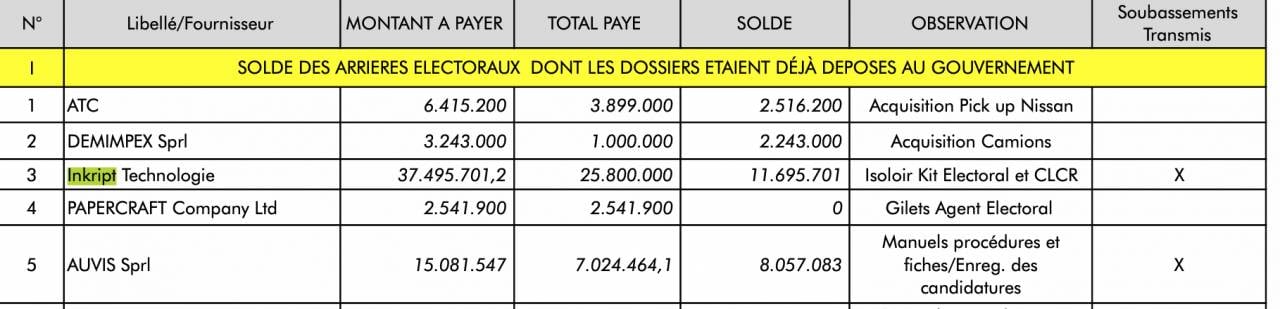

According to the 2013-2014 fiscal year report of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), which is in charge of procurements, the amount due to a company called Inkript Technologies hit $37.5 million, including $25.8 million that had already been paid.

The electoral material market for the 2011 elections was awarded to Inkript Technologies in 2011. (Source: CENI report 2013-2014)

The electoral material market for the 2011 elections was awarded to Inkript Technologies in 2011. (Source: CENI report 2013-2014)

The report, which was submitted to the Congolese Parliament, is one of the independent institution’s only documents that include information on the contracts, the amounts and the beneficiaries involved.

Electoral jackpot

However, the leak of more than 3.5 million BGFIBank documents and millions of transactions — obtained by the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa (PPLAAF) and Mediapart, and shared with its partners, including L’Orient-Le Jour — unveils the major role the INEC assumed in numerous financial irregularities that have marked various elections in the DRC.

It all started on Jan. 20, 2011, when the Congolese Parliament passed, at Joseph Kabila’s initiative, a revision of the 2006 Constitution allowing for the president to be elected by a simple majority, facilitating the re-election of the outgoing candidate.

Kabila had already chosen his champion to lead the INEC: Pastor Daniel Ngoy Mulunda, a founding member of the People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD). Even before his appointment, Mulunda identified which bank to open the INEC’s accounts at: the Congolese subsidiary of BGFIBank, run by Francis Selemani Ntwale, the head of state’s brother.

A few months later, the INEC officially opened accounts at BGFIBank RDC on June 3, 2011. The first transfers were made late that month, and the BGFIBank RDC’s director was invited to Kabila’s inauguration, marking the outset of their privileged relations.

Since then, INEC’s accounts at BGFIBank have been tainted with irregularities and anomalies, while the INEC’s management took no measures to stop it. While the primary misappropriation of funds discovered took place during the 2016–18 electoral cycle, similar mismanagement was detected during the 2011 cycle.

The INEC is no stranger to these irregularities, even if the $25.5 million channeled to its accounts at the BGFIBank RDC make up only a tiny amount of the total electoral budget.

Spending during the 2011–12 electoral cycle, including one round of the presidential election and the legislative elections, hit nearly $700 million, the INEC communicated to BGFIBank, as per the documents obtained by Congo Hold-Up — a third of which is funded by the international community. This is compared with $546.2 million spent on the five elections and the constitutional referendum held from 2005 to 2006.

While the colossal spending increases were justified by the urgency of holding the elections, an analysis of INEC’s accounts points to numerous suspicious transfers, made in particular to businessmen who are directly associated with the presidential clan.

For instance, more than $4.3 million in transportation services were transferred to Service Air, an air freight company run by Harish Jagtani, a close associate of the former president’s clan.

The beneficiaries of these companies suspected of overcharging for their services include two vice presidential candidates from the former president’s political blocand current ministers. The $19 million contract for printing services shows that these companies’ rates were sometimes three times higher than the price anticipated in the INEC’s 2018 budget.

Confusing questions

When it comes to the contract for the supply of electoral material, the amount pledged in 2011 is the most striking: $37.5 million, which is two times higher than that for the 2016–19 electoral cycle, despite the fact that the number of polling and vote tallying centers increased in the meantime. According to the information obtained, $5 million were paid via two transfers, made on July 11 and July 15, 2011, from the INEC account at BGFI—RDC to a Congolese company named Inkript Technologies SPRL.

On July 9, a Lebanese citizen named Frederic Fayad held 60 percent of the company’s shares, and a Congolese national named Deogratias Kakwata Mbama held the other 40 percent, according to the official register.

Why create a new company in the DRC, just after the Lebanese company was awarded the contract, to receive the transfers? While Congo Hold-Up investigations did not reveal any irregularities that would be directly attributable to Inkript in this contract, these questions are far from confusing those who are very familiar with local practices.

“In Congo, the elections present an opportunity for political leaders, their cronies, including the INEC, and their financial partners to ensure massive misappropriation of funds. The contracts are awarded under opaque conditions, which is a violation of the procurement law, and overcharging for goods and services is very common,” said Florimond Muteba, chairman of the board of the Observatory of Public Expenditure, an NGO that scrutinizes the management of Congolese public finances.

“The surplus is then shared among the partners, sometimes with the help of foreign facilitators in setups that involve Congolese companies, whose sole objective is to manage the misappropriated funds on the spot,” he added.

These suspicions were denied by the Lebanese company, which claimed that “‘Inkript DRC’ is not related to Inkript Industries and neither are the persons mentioned above,” and but said that after a dispute over the use of the name, it had entered into an agreement to act as a “subcontractor” of the latter.

“At the time, we were not notified beforehand that the company was established using “Inkript” name by third parties without authorization by Inkript. ” it added.

“After escalating the matter and several negotiation phases,” the Lebanese company said, Inkript Industries executed a subcontract, allowing Inkript Technologies to use its brand name “for a limited time and purpose. .”

However, the company is still mentioned in the Congolese trade register to date. As for the suspicions of potential overcharging for the amount of the contract, Congo Hold-Up could neither confirm nor deny them.

While Inkript indicated that it has received only a part of the $37.5 million mentioned by the INEC as a subcontractor, it affirmed getting “ paid in a timely manner” for the fulfilment of its obligations. As for the remaining issues, it threw the ball in the court of “INEC or the competent authorities in charge of managing or overseeing these elections.”

The INEC declined to answer our calls. As for its former president, Mulunda, he is currently serving a three-year prison sentence for “stirring tribal hatred, circulating false rumors and undermining state security.”

For its part, Inkript continues to flourish in Kinshasa: It was selected in May by a local company as subcontractor as part of the secure vehicle sticker (RFID) management system project.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury

To our readers,

Following the publication of this article, we received a response from Me Nabil Maad, lawyer of the company Inkript. Extracts of his remarks are reprinted below:

"The insinuations and facts reported in this article are erroneous, to say the least, and your newspaper had the duty to ensure their veracity before the publication of the article in order to avoid an infringement of the rights of my client and her reputation.

Indeed, L'OLJ did contact Inkript before the publication of the article. However, the author consciously decided to reproduce only a small part of the company's comments. This makes us question the true intention of this kind of article (...). Inkript had specified the following in particular:

- Regarding the project in the Central African Republic, Inkript's subsidiary ‘Africard Co RCA’ won the tender for the issuance of biometric passports in 2010 and since then, it has been managing the said operation under the supervision and control of the local authorities concerned, as well as the CEMAC Commission (Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa). In 2014, and contrary to what the article insinuates in a completely erroneous and above all malicious manner, Africard received praise (...) from the CEMAC homologation commission for the work undertaken.

- Regarding the elections project in the Democratic Republic of Congo, your article’s insinuation that my client was involved in any suspicious activity is unacceptable and rejected. The article itself confirmed that the study of multiple documents proved without a doubt that Inkript is well deserving of its success and regional reputation, especially in the field of secure printing.

- Inkript (...) which was only the subcontractor in the DRC elections project, is in no way linked to the local company in charge of the overall project; the author has made this clear, as the shareholding is not linked to Inkript at all. In fact, when Inkript executes any project as a concessionaire or prime contractor, it clearly does so directly through a local company or an Inkript group company in which it expressly holds all the shares.

The allegations in the article that imply any suspicion of impropriety or on the part of the company or its involvement in any illegal activity or deal are entirely false and therefore rejected.(...)

For that, I ask you to publish these clarifications and to withdraw from the electronic version of the said article (in French and English languages) any defamatory and unfounded reference to the Inkript company and to refrain from damaging its reputation in any way whatsoever (...).

Nabil MAAD

Lawyer at the court."

Editorial clarifications:

As Lebanese law requires L'Orient-Le Jour to reproduce all or part of this right of reply, the editorial staff of L'Orient-Le Jour agreed to this request, but it contests the validity of all of its assertions and wishes more particularly to make the following clarifications:

Regarding the production of biometric passports in the Central African Republic by Africard Co RCA, the offending article is content to report — simply for the sake of contextualization and presentation (since this case is not the subject of the article) — "suspicions" relating to "the manufacture of passports of convenience under a contract signed in 2010 under the mandate of François Bozizé." These suspicions are duly sourced to the information reported by Jeune Afrique. Our article also reports the response of Inkript, which considers the production of passports in CAR to be done "under the supervision and to the full satisfaction of the (...) competent authorities" (which implicitly includes the CEMAC).

Regarding the electoral materials contract in the DRC, the article states clearly that "Congo Hold-Up investigations did not reveal any irregularities that would be directly attributable to Inkript in this contract" and simply mentions the various suspicions that weigh on the furniture of the electoral material in a global manner. It also mentions the relevant elements of the company's response to our questions. On the other hand, and contrary to what is indicated in Mr. Maad's letter, it does not give any opinion regarding the fact that "the Inkript company deserves its success and its regional reputation" - for the simple reason that this is not its purpose.

Therefore, L'Orient-Le Jour sees no reason to modify any part of this article.