Kassem Tajeddine (Credit: NNA)

The Tajeddines, a Lebanese Shiite family who made their fortune in Africa, are at the heart of a financial scandal exposed by the Congo Hold-Up investigation in which L’Orient-Le Jour took part.

The investigation was carried out following a leak of more than 3.5 million documents and millions of detailed transactions issued by BGFIBank, which were obtained by The Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa (PPLAAF) and Mediapart, an independent French online investigative journal, and shared with the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC), and its media partners, including L’Orient-Le Jour.

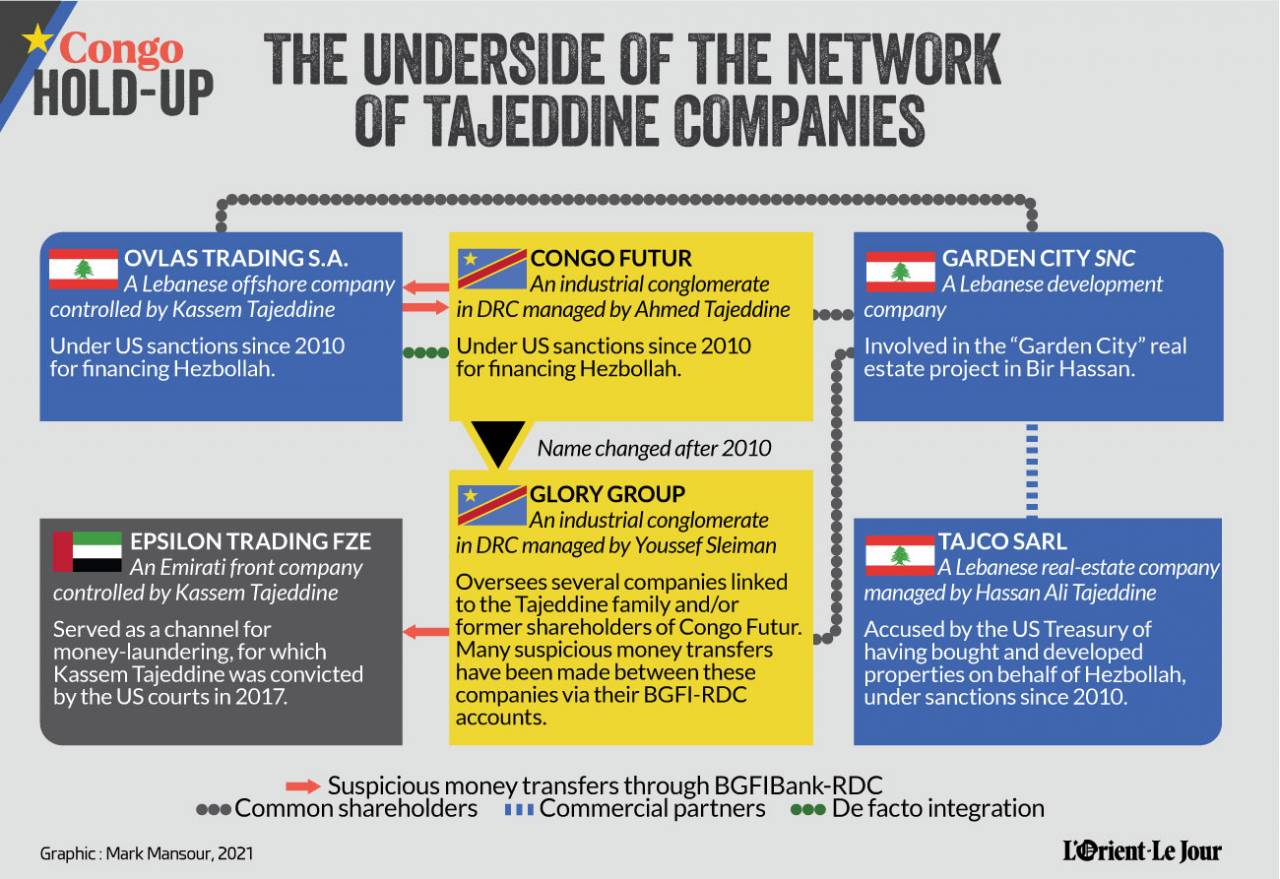

While three brothers of the Tajeddine family are currently under US sanctions for financing Hezbollah, the companies linked with the Tajeddine network are among the largest customers of the Congolese subsidiary of the bank.

The Congo Hold-Up investigation showed that this bank was used to embezzle more than $138 million in public funds from the Democratic Republic of Congo, mainly for the benefit of the clan of Joseph Kabila, the former president of the DRC.

- The Lebanese side of the investigation also shows how BGFIBank RDC served as a platform for the expansion and renewal of a network of companies associated with Congo Futur. This industrial conglomerate, which is under American sanctions for financing Hezbollah, is held by one of the Tajeddine brothers, Ahmed Tajeddine, who is also convicted of financial crimes by the Belgian courts. This scheme was made possible by the financial elite of the DRC, the sixth poorest country in the world.

- The bank has, in fact, allowed these companies access to the international banking system for years, despite US sanctions and warnings from correspondent banks. Several tens of millions of dollars have been transferred from BGFIBank to accounts abroad held by Kassem Tajeddine, one of the Tajeddine brothers who is blacklisted by the US.

- In Lebanon, the US treasury accuses the Tajeddine family of operating “to purchase and develop properties in Lebanon on behalf of Hezbollah,” via Tajco SARL. Although Kassem Tajeddine said he no longer had ties to Tajco or Congo Futur, the Congo Hold-Up investigation shows the ongoing ties between real estate investment involving Tajco, as well as people linked to Congo Futur and a company controlled by Kassem Tajeddine.

“It was him who paid for my husband’s heart operation,” said a resident of Hanawei, near Sur, gratefully to an Al Jadeed TV channel reporter who was conducting a round of interviews about Kassem Tajeddine in his hometown back in March 2017.

“He employed maybe 500 people in Africa from the village and the whole of the South,” another man told the camera, speaking about the Belgian Lebanese businessman.

At the time, the philanthropist who was praised by everyone had been arrested a few days earlier in Morocco and was to be extradited to the United States, where he is considered by US courts as one of the main funders of Hezbollah, and was accused of having restructured his business empire in order to circumvent the sanctions against him.

Kassem Tajeddine’s name is now closely linked to the Congo Hold-Up financial scandal.

This investigation, which is coordinated by the EIC, in collaboration with 20 other partners, including NGOs and media partners, among them L’Orient-Le Jour, is based on a leak of more than 3.5 million documents and details on millions of transactions from BGFIbank (see article introduction).

The investigation reveals that businesses related to the Tajeddine family are among the biggest customers of the local branch of BGFIBank, which is affiliated with Joseph Kabila, the former president of the DRC.

It was mainly through Congo Futur — a food, construction and diamond mining conglomerate — that the Tajeddine family came to prominence. The controversial company has been under US sanctions since 2010 for “funding Hezbollah.”

For his part, Kassem Tajeddine, was added in 2009 by the US Treasury’s OFAC to the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List (SDN) for his involvement in Tajco SARL, accused of purchasing and developing properties in Lebanon on behalf of Hezbollah.

A number of corroborating clues collected as part of the Congo Hold-Up investigation suggest that BFGIBank RDC served as a platform for a network of people and companies accused of being affiliated with the Shiite militia, allowing them to access the international banking system.

In a memorandum sent to a US court in July 2019, Kassem Tajeddine’s lawyers described his “exceptional” rags-to-riches story, and how he grew up in a one room house without plumbing, indoor toilet or electricity until his big break in Africa — a success story that he owes only to his “hard work.”

It all began when Tajeddine left for Sierra Leone in 1976, a year after the outbreak of the Lebanese 1975-90 Civil War. He was then 21 years old. He started out by helping out at a relative’s grocery store, before opening his own business two years later.

In the mid-1980s, he moved to Ivory Coast and then headed for Belgium in 1989, where he set up the headquarters of his companies, while his African businesses developed and took off during the following decades.

Future Tower, in Kinshasa. (Credit: Sonia Rollet/RFI)

Future Tower, in Kinshasa. (Credit: Sonia Rollet/RFI)

The family conglomerate Congo Futur was founded in 1997 and managed by his brother Ahmed. It would become the emblem of the success story. Based in the very modern Future Tower in the business district of Kinshasa, the company would become a major player.

Its stores are scattered all over the country: along the bustling boulevards of the capital city, as well as along the paths through small villages, where the company often monopolizes the import of basic necessities.

Thanks to its links with the Kabila clan, the group was one the official subcontractors of the state and had control over many public markets.

Ahmad Tajeddine, brother of Kassem and director of Congo Futur. (Credit: Photo taken from his Facebook page)

Ahmad Tajeddine, brother of Kassem and director of Congo Futur. (Credit: Photo taken from his Facebook page)

‘Everyone loves Hezbollah’

But things took a turn for the worse in 2003: Belgian police raided the offices of the Soafrimex, a food trading company based in Antwerp and run by Kassem Tajeddine.

The initial investigation was based on a tip sent to the Antwerp prosecutor back in 2002 by the State Security (VSSE), the Belgian intelligence and security service. The memo expressed suspicions about Soafrimex, mentioning trade in “blood diamonds” and financing Hezbollah.

For several months, Belgian investigators deployed significant resources and even traveled to Lebanon in a bid to understand the purpose of the transfers but failed to find any concrete evidence to support the accusations of terrorist financing or smuggling diamonds.

Their investigations, however, revealed that false invoices had been drawn up, which made it possible to conceal the source of more than 50 million euros.

The invoices that were made out for customers, the largest of which was Congo Futur, were systematically for a lower amount than the invoices Soafrimex kept in its own books.

At the end of 2009, the Antwerp Court of Appeal delivered its final verdict, convicting Kassem Tajeddine, as well as his wife and his two brothers, Ahmed and Jaafar Tajeddine, of “forgery and money laundering” and sentencing them to up to two years in prison.

One month after the Belgian verdict, it was the turn of American courts to prosecute the Tajeddine brothers.

In 2009, US Treasury’s OFAC added Kassem Tajeddine to SDN, accusing him of having contributed to the financing of Hezbollah to the tune of “tens of millions of dollars” via his brother Ali.

The news was a hammer blow, as being on the list meant he could not carry out any transactions in dollars, except with a special license.

In other words, the businessman and the companies he owns were banned from accessing the global financial system.

The following year, the US imposed sanctions on Ali Tajeddine, accused of being a former commander for Hezbollah in Hanawei.

“I love Hezbollah. Everyone loves Hezbollah … But I have no relations [with them],” Ali Tajeddine said in a 2016 interview with The Wall Street Journal.

But his accusers had a different view on the matter.

“Since at least December 2007, Ali Tajeddine used a company called Tajco Sarl, operating as Tajco Company LLC, as the primary entity to purchase and develop properties in Lebanon on behalf of Hizballah,” according to the US Treasury.

“Tajco was at the time one of four private construction companies close to Hezbollah,” said Joseph Daher, a political scientist at the University of Lausanne.

Tajco was established in 1995 by Ali, Mahmoud, Youssef, Ibrahim and Kassem Tajeddine. At the time, each of the five brothers owned 20 percent of the company, according to the Lebanese trade register.

In the crosshairs of American courts were massive purchases of land between Jezzine and the Bekaa valley.

“At the end of the conflict with Israel, Hezbollah moved north of the Litani River, into the hills near the small Christian village of al-Qatraneh and the Druze village of al-Sreiri. At the time, the Christian and Druze local residents I met told me about massive real estate investments in their area. Behind these purchases was Ali Tajeddine, who was paying cash to the inhabitants of the region to acquire their land. The goal appeared to be intended to create a Shiite belt between Nabatiyeh and the southwestern Bekaa in order to provide Hezbollah with a uniform confessional territory," says Nicholas Blanford, a Beirut-based researcher at the Atlantic Council.

During his investigation on the subject, the researcher said he met Ali Tajeddine in 2007.

“He did not deny the facts, but he told me that it was a commercial investment for employees of any faith working in quarries. He was specifically referring to the village of Ahmadieh (Hasbaya district) east of Quatraneh, which is Shiite," Blanford said.

Hassan Tajeddine, Ali’s son and the current CEO of Tajco, told Congo Hold-Up that his company — currently in liquidation — had “no role” in the land purchases made by his father. He also claimed to have never carried out transactions on behalf of Hezbollah, with which he has “good relations like [with] the other parties.”

Kassem Tajeddine claims that the complex ties between his brothers and the Shiite party have led the American investigators to get ahead of themselves.

In an article published in May 2016 by the online magazine Tehran Bureau, Kassem Tajeddine’s lawyer at the time, Chibli Mallat, mentioned a confusion between his brother Ali’s real estate investment and his own.

This is what he reiterated in a letter sent via his lawyer to Congo Hold-Up.

“I suffered a lot from conflation of facts and persons during my legal struggles in the United States and continue to suffer from it here,”” Kassem Tajeddine wrote.

“I have always maintained that my listing as a so-called [Specially Designated Global Terrorist] (SDGT)cwas improper, and that I never provided financing or any other support to any terrorist organization or Hizballah,” he added.

The US administration, however, continues to be convinced otherwise, without disclosing the evidence in its possession allowing it to justify the accusations it has leveled.

Due to the lack of access to these still-classified documents — as confirmed by a US Treasury spokesman to Congo Hold-Up — the consortium could not verify them.

‘Land purchasing strategy’

Kassem Tajeddine’s concerted efforts to be removed from the US blacklist were in vain.

He “ceas[ed] all commercial and financial dealings with Tajco Ltd., Congo Futur and any other company owned or held by his brothers or other designated as SDGTs,” Kassem Tajeddine’s lawyers said in a letter addressed to OFAC.

“As for his initial stake in Tajco, from which he claims to have withdrawn in 2010, it was limited to matters of corporate formality,” the letter continued.

However, Hassan Tajeddine, the CEO of Tajco, said he had bought his uncle’s shares in April 2006, and not 2010, according to a document obtained by Congo Hold-Up.

The document is indeed stamped by the notary in 2006, the registration with the commercial register, which is necessary for the officialization of the transfer of social shares and to become enforceable for third parties, is dated in 2014.

“It is common to have a delay between the two stages, especially due to slow administrative procedures. But eight years is difficult to explain, especially for an influential Shiite businessman,” the aforementioned lawyer said.

“But sometimes, some manage to convince overly lax notaries to backdate such documents,” he added.

The Congo Hold-Up investigation sought to shed light on real estate investments in Beirut’s suburbs, in which Tajco is allegedly involved as well as entities controlled by Kassem Tajeddine and personalities affiliated with Congo Futur.

Among these investments, Garden City is notable. A residential and commercial development project in Beirut’s Bir Hassan neighborhood, it “has been the object of a strategy of appropriation of the territory implemented by various Shiite developers close to Hezbollah and Amal,” according to Yasmine Hassan Farhat, a researcher who carried out research on land purchases based on sects in Bir Hassan.

“This involved entrusting the development of the area to ‘approved developers,’ a Shiite elite very well connected with the power, like the Tajeddines,” she said.

“The company Garden City bought the land on which it was built in 2007 and in 2010, Tajco, one of the main developers, was entrusted with the implementation of the residential project,” Farhat added.

According to the Lebanese trade register, which was reviewed by Congo Hold-Up, there was indeed a company by the name of Garden City SNC that was founded in 2008 and located at the time at the Tajco headquarters in Bir Hassan, a few steps from the real estate project in question.

Garden City is a residential and commercial real estate development project in Bir Hassan. (Credit: NMA Photo)

Garden City is a residential and commercial real estate development project in Bir Hassan. (Credit: NMA Photo)

The names of some founders and shareholders of Garden City are also linked to Congo Futur as well as to Ovlas Trading SA, a Lebanese offshore company controlled by Kassem Tajeddine (see BankMed article). None of these shareholders responded to Congo Hold-Up’s questions.

Hassan Tajeddine, the director of Tajco, wrote that his firm partnered with Garden City SNC for consultancy work and subsequently acted “as a broker to sell properties.” He asserted, however, that he has no commercial link with Congo Futur or Kassim Tajeddine.

From Congo Futur to Glory Group

While the stranglehold of the US sanctions would eventually lead to the official disappearance of Congo Futur, the Tajeddine corporate octopus managed to find ingenious ways to reinvent itself and continue to thrive after the imposition of US sanctions with the help of BGFIBank RDC.

A new conglomerate called Glory Group was formed to manage several companies that took over a series of activities that were once the mainstay of Congo Futur, including Simmokin real estate, the Société Congolaise de Construction Moderne (SCCM), Cotrefor logging firm and Union Invest.

All of these companies are de facto run by Youssef Sleiman, who is also co-shareholder of another company with the wife of Ahmed Tajeddine, and his associate Abed Hassan Farhat, a shareholder of Congo Futur, according to the 2012 edition of the Congolese Journal Officiel.

Their accounts, which, according to BGFIBank RDC belong to Glory Group, received large cash deposits.

Hundreds of thousands of dollars — often appearing in round numbers and in single transfers — also flowed between these accounts without reference to any goods being traded.

This new corporate network was also successful in making international transfers with the help of the Congolese bank.

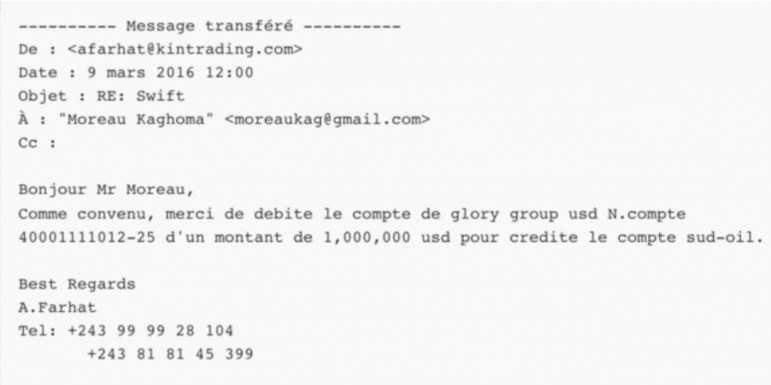

The leaked documents show that Abed Hassan Farhat and operations director Moreau Kaghoma developed a scheme to conceal the actual senders of transfers made by one of the subsidiaries of Glory Group in order to escape control by correspondent banks.

The Kabila clan bank was not the only one to host a multitude of company accounts linked to Congo Futur. The local branch of the Nigerien bank Access Bank, which is based in DRC, was also involved.

“Three people managed all the accounts, including Abed Hassan Farhat and Youssef Sleiman. They were establishing a new company almost every month. We never saw the official shareholders, who were employees of Congo Futur,” Israel Kaseya, a whistleblower, told Congo Hold-Up.

When contacted, Access Bank was unable to comment on these claims.

“And when we had to freeze the SCCM account following a report from our correspondent bank, they went so far as to open shell accounts. They did not provide any legal documentation on their nature or the identity of their holders,” Kaseay said.

These statements were firmly denied by the SCCM, which indicated, in a letter to Congo Hold-Up, to have “found other means to regain [its] rights [and to remain] in conformity with the Congolese laws.”

Suspicious transfers

The BGFI’s preferential treatment toward its client can be explained by the privileged relations it maintains with them, which is highlighted in a 2015 document from the bank, noting that the conglomerate companies are among the bank’s “main providers of cash.”

Relations with the group “are going very well,” read another email addressed to the customer relations manager within the bank.

These findings contrast with the many concerns raised in 2011 by the correspondent banks in their correspondence with BGFIBank RDC as to the potential links between its clients and Congo Futur (see our other articles).

Some suspicious transfers might explain the bank’s leniency toward Glory Group.

The massive data leak showed that a bank transfer of $1 million was transferred in March 2016 to the company Sud Oil, which is a front company, involved in another major embezzlement of public funds scandal revealed by Congo Hold-Up.

Sud Oil is effectively controlled by Francis Selemani, the adoptive brother of Joseph Kabila and president of BGFIBank RDC until 2018.

One month earlier, a cash deposit of $705,500 was also booked on the account of Glory Group and then credited to Sud Oil. The bank transcripts did not indicate any specific reason for the transactions.

Transfer of $1 million from Glory Group to Sud Oil. (Credit: PPLAAF / Mediapart document)

Transfer of $1 million from Glory Group to Sud Oil. (Credit: PPLAAF / Mediapart document)

The leak from the BGFI also showed that, contrary to what he told OFAC, Kassem Tajeddine continued to maintain commercial relations with companies affiliated with Congo Futur.

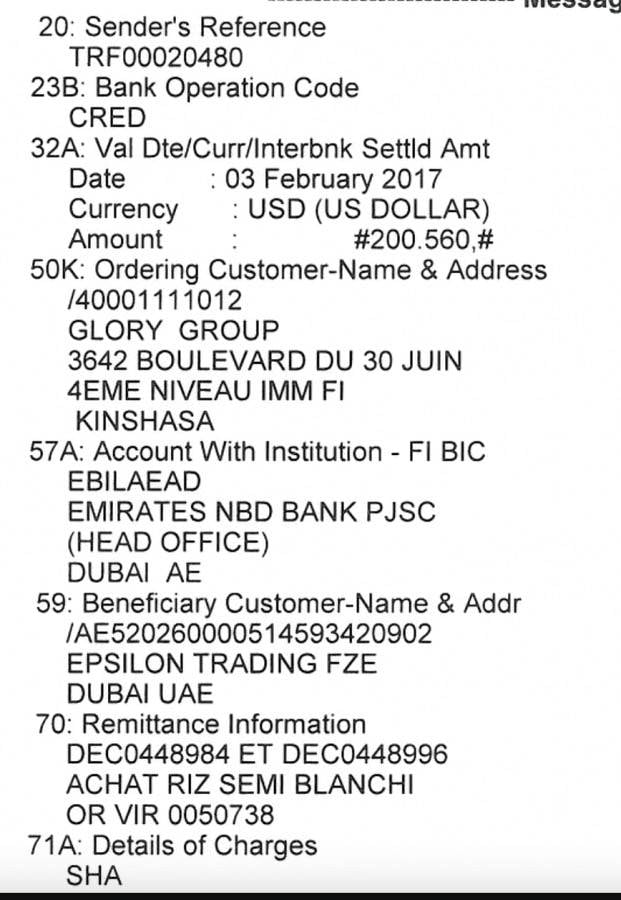

Glory Group has made transfers in foreign currency from its accounts at BGFI to entities controlled by Kassem Tajeddine, despite the sanctions.

Epsilon Trading FZE, a letterbox company, with no website or official email, registered in the UAE, received more than $88 million between 2013 and 2017 (see our article) from these companies that are affiliated with Glory Group for the purchase of goods ranging from various food products to diesel engines.

In 2018, Kassem Tajeddine admitted to a US court that he used the same company to launder money and circumvent US sanctions against him.

In his response to Congo Hold-Up’s questions, Kassem Tajeddine refused to “speak for any of the transactions regarding these companies and individuals,” but he denounced the “conflation” in the way the operations of companies are presented, “linked to one another haphazardly and, in turn, presented as one and the same entity which is allegedly responsible for certain actions.”

“I do find it astonishing that no attempt has been made to look at the legitimacy of the transactions,” he added.

Turnaround

After his extradition to the US, Kassem Tajeddine was accused before the courts there of having restructured his commercial empire, by creating new entities, notably in the UAE, and of having concealed his identity to circumvent the sanctions against him.

This scheme enabled him, according to the indictment, to make more than $27 million in illegal transactions with US entities. In 2018, he pleaded guilty to “conspiracy to launder money.” He was sentenced to pay a fine of $50 million and five years in prison.

In July 2020, however, things took a different turn with his early release after two years in prison, ostensibly for health reasons.

But several media outlets linked Kassem Tajeddine’s release to a prisoner swap deal between Washington and Tehran — which also included the Lebanese-American and ex-militiaman of the South Lebanon Army Amer Fakhoury, who was released a few months later in Beirut.

Kassem Tajeddine categorically denied any association of this type.

“As proven by US court documents, my release was exclusively a case of compassionate release, and not a part of a broader deal or prisoner exchange,” reads the letter he sent to the consortium.

The businessman returned to Lebanon and has lived there ever since.

His homecoming in July 2020 was festive. When he arrived in his native Hanawei, he was paraded through the village in an open-roofed black Mercedes SUV, escorted by countless men on cars, scooters and dirt bikes. He was warmly welcomed by the villagers, who showered him with rice and flower petals.

This project was financially supported by the Investigative Journalism for Europe (IJ4EU) fund.

Correction: This article was modified on 12/7/2021 to correct a calculation error on the total amounts of transfers to Epsilon bank accounts.