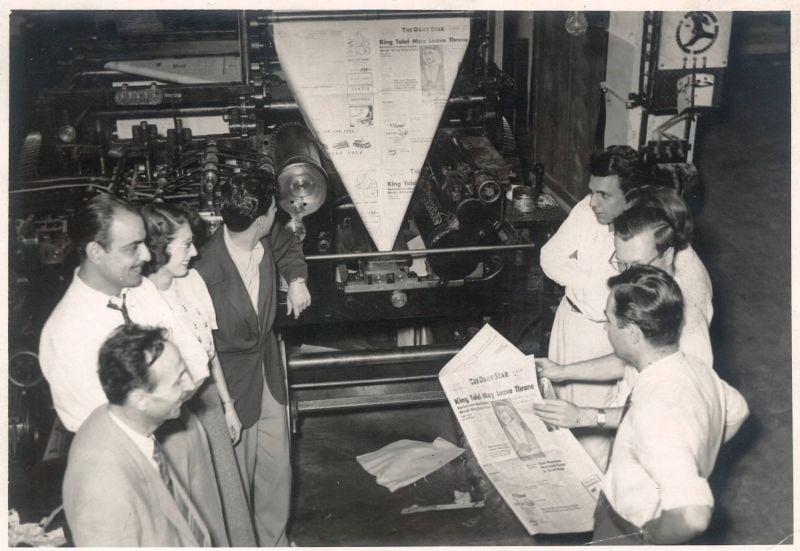

The first issue of The Daily Star being printed on June 3, 1952 in Dar Al Hayat, with publisher Kamel Mrowa pictured first from the right. (Credit: courtesy of Kamel Mrowa Foundation)

BEIRUT — On Nov. 1, the few remaining employees of Lebanon’s long-running English-language newspaper The Daily Star were notified that their employment had been terminated the previous day and the outlet was closing up shop.

Lebanon had lost one of its last remaining newspapers. The sparse media landscape of 2021 stands in stark contrast to the 56 dailies and weeklies that had been in circulation when The Daily Star was launched in 1952.

This was not the first time the newspaper had ceased publication, but to many, it felt like the end of an era.

Some took to social media to mourn the paper’s glory days.

Others expressed hope that it might return, as it has before; still others questioned whether it should be mourned at all.

As Habib Battah, a former reporter and editor at the publication who now teaches journalism at the American University of Beirut and runs the website Beirut Report, put it: “The Daily Star meant a lot of different things to different people. No publication exists in a vacuum.”

How it began

The Daily Star was founded by publisher Kamel Mrowa as the English-language sister publication of the pan-Arab newspaper Al-Hayat. At the time, it was not uncommon for newspapers to have a companion publication. The French-language L’Orient had the Arabic Al-Jarida, and its rival French publication, Le Jour, had the English The Eastern Times. The Daily Star would eventually launch a French edition too, Beyrouth Matin, in 1956, which merged with Le Jour and relaunched in 1965. Kamel’s youngest son, Malek Mrowa, explained to L’Orient Today that the merger came out of an agreement between his father and the publisher of An-Nahar, Ghassan Tueni, that stipulated Tueni would not touch the English press as long as Kamel did the same with the French press.

The Daily Star’s first editor-in-chief, C.B. Squire, told The New York Times that the paper’s purpose was to present news in an American fashion. Its readership consisted of foreign journalists, the jet set and the occasional intelligence agency, whose agents would cite articles they had perused over morning coffee, as shown in declassified documents.

This widely connected audience led to the republication of articles in international dailies such as The Times of London, and to consistent citations in The New York Times and The Chicago Tribune, as well as on the Associated Press and Reuters wire services. Additionally, stories from The Daily Star would be translated to Arabic for Al-Hayat three times a month.

Politically, many claimed that Kamel Mrowa’s editorial stance was “pro-Saudi and anti-Nasserite,” as the academic Caroline Attie described it. But Kamel’s family disputes this characterization. Malek told L’Orient Today that his father was “a friend of the Saudis but he was more of an Arabist.” He added that against the political backdrop of the 1950s and ’60s, “a lot of [newspapers] were with Nasser or the leftist movements and my father was outside of that.”

“Show me one article where my father was against Nasser,” Jamil Mrowa, Kamel’s eldest son said. He explained that Kamel’s articles mainly lamented Nasser’s growing militarism and “his adoption of a socialist agenda.”

However, Kamel Mrowa’s political stance made him and The Daily Star a target for attacks. The first was in 1957, when a bomb was set off in the paper’s office in Ghalghoul. It was followed by another in 1960, when a stick of dynamite was thrown through the office’s windows. In both cases, no one claimed responsibility. Finally, in May 1966, Mrowa was assassinated at the age of 51. The next day local newspapers went on strike in protest.

Mrowa’s assailant, Adnan Sultani, a 28-year-old bank messenger, was sentenced to death but escaped during the 1975-90 Civil War and died in 2001 at an undisclosed location. It was later revealed that he had been working for the Egyptian intelligence services.

Following the assassination, Mrowa’s widow, Salma Bissar, and their son Jamil kept the newspaper alive. But the attacks continued, with another explosion rocking the paper’s offices a few months after Kamel’s death, followed by another bombing in 1970.

The war years

When the Civil War erupted in 1975, 24-year-old Jamil tried to keep the paper going, but he faced a new set of constraints. Many journalists and photographers were being attacked or killed; sniper fire took the life of L’Orient-Le Jour’s editor, Edouard Saab, as he was trying to cross the so-called Green Line dividing east and west Beirut in 1976.

Because The Daily Star’s offices were close to the Green Line, going to work “became a case of writing your own will,” Jamil recalled. The publication therefore was left with a skeleton staff, and the paper couldn’t print at another publisher because they didn’t have English typecasts. So in May 1976, The Daily Star folded for the first time. Al-Hayat followed suit two months later.

After going dark for seven years, The Daily Star reopened in 1983 when it seemed peace would set in. Using a bank loan, Jamil and Malek moved their offices to Hamra behind the Commodore Hotel.

On the day of the relaunch, fighting erupted, shattering the office’s windows; an omen that this era of The Daily Star would be short-lived.

American writers were recruited as part of the new staff, including Anne Friedman, whose husband Thomas was The New York Times Beirut bureau chief at the time. But this later turned into a liability, as the deteriorating security situation put the lives of foreign reporters at risk. Malek recalled, “a lot of them were kidnapped and we had to get them back.”

The security situation also made publishing difficult. The printing plant was still in Ghalghoul next to the Green Line. To get there, staff sometimes had to drive through tunnels carved out of abandoned houses to avoid snipers.

“You [would] drive there at two o’clock in the morning and you [would] turn off your lights and you [would] drive through the tunnel made of three to five houses,” Malek recalled.

Additionally, the readership began to decline: diplomats, professors and what was left of the expatriate community were fleeing the country en masse.

As former editor Peter Grimesditch put it to The Guardian in a 1996 interview, “I remember standing watching most of our bloody readers going off by helicopter. There were so many people being kidnapped, it was silly to stay.”

By 1985, The Daily Star had to move from publishing daily to weekly, before folding once more in 1986.

Reconstruction

However, the seeds were planted for the third era of The Daily Star. Grimsditch maintained good relations with Jamil Mrowa and, after the war, returned to Beirut to help reopen the paper. The aim was to capitalize on the optimistic mood after the end of the Civil War, and so The Daily Star was relaunched for a third time on June 18, 1996 — this time as a 16-page broadsheet with six British journalists and a circulation of 4,000.

By then, the paper’s readership had evolved from its traditional expatriate base, Malek said. “The market became the Lebanese” who were returning from, or were born, abroad.

Soon, it would grow into a much larger regional operation working from a two-story office in Gemmayzeh with 40 reporters. A joint-publication venture with the International Herald Tribune in 2001 gave The Daily Star a regional presence with a distribution network in the Gulf.

Jamil explained, “The concept was that the International Herald Tribune would be the international section, The Daily Star, the regional section, with co-publishing agreements with various publishers across the region: Al-Watan in Kuwait, The Peninsula in Qatar … Al-Ahram in Egypt.”

Operations included daily simultaneous printing in four Arab cities as well as special car delivery from Beirut to Damascus and Amman.

Because of this, The Daily Star became a hub for young media professionals from around the world. Battah was one of them.

“It was a fun time to be a journalist,” he said. “Most of the reporters and editors were in their 20s. It was like a college computer lab, very casual.” He noted that with the work they produced “we got to shine a light on the lives of ordinary people.”

However, he added that there were redlines not to be crossed.

“We had to keep good relations with businesses for the sake of advertising”, he said. “We ran into pushback sometimes.”

Battah added, “The Daily Star was never critical of power the way it paints itself today but we did shed light on the beauty and culture of the country.”

New struggles, new ownership

But new struggles arose in the wake of Rafik Hariri’s assassination in 2005 and the 2006 war with Israel. Despite having a lot of news to write, The Daily Star entered “a period of revenue turmoil” as Jamil put it, as advertising revenue plunged due to the security situation. The paper’s regional presence began to diminish as the owners could not continue investing in it, and their Arab partners began setting up their own English-language dailies.

To make matters worse, a loan from Standard Chartered Bank, dating from at least 1999, was called in in the midst of the turmoil. As a result, the paper closed for a third time on Jan. 21, 2009, after its creditor filed a court order to declare it bankrupt. The newspaper shut immediately without prior notice. Finally, after two weeks of closure, Mrowa got the order reversed.

Jamil reached out for new partners, and, after a deal with a Qatari publisher fell through, he approached Prime Minister Saad Hariri and the paper was sold to a company owned by the Hariri family. A spokesperson for Hariri declined to comment. He referred L’Orient Today to The Daily Star’s editor-in-chief, Nadim Ladki, who did not respond to a request for comment.

Malek was approached to serve as chairman so that “they did not have to change the name of the company, and I stayed completely free of charge,” he said.

This was merely symbolic, he added: “I did not sign anything. They didn’t even tell me [when] they closed it.”

As for his 0.007 percent ownership, Malek explained that as chairman, he legally has to own at least one share of the company.

The new management took over in October 2010, and the newspaper’s offices were later moved from Gemmayzeh to Downtown. However, the stability the sale offered was short-lived.

Wassim Mroue, who worked there as a reporter and editor from 2010 to 2016, recalled, “The paper did well from fall 2010 until around spring or summer 2015, when we began to witness salary delays.”

These problems were persistent. Kareem Chehayeb, now the Beirut correspondent for Al Jazeera English, who was a reporter at The Daily Star in 2018, said, “After I was paid for the first couple of months, I had to wait many many months to get paid. At times, you would be paid [a] half salary instead of a full one so you can pay your rent.”

Battah noted that during his time there in the early 2000s, there had also been labor issues, with foreign reporters often making as much as 50 percent more than local staff.

Despite these tensions, The Daily Star continued to produce high-quality journalism because “the journalists that were there were passionate and worked very hard,” Chehayeb added.

Like many Lebanese media outlets, The Daily Star was tied to a political figure: in this period, Hariri. Nevertheless, former employees said they were largely able to report without censorship.

“There were red lines, but they were very implicit compared to other Hariri-owned publications,” Chehayeb said. Although he noted that the paper tended to play up good news related to Hariri, while “any accusations lodged against Hariri were never amplified,” he noted that when it came to reporting the news, “the publication retained a rigorous editorial policy.”

Another end and a possible new beginning

In late 2019, amid the mass protests that had begun on Oct. 17 and against the backdrop of six months of unpaid wages, and the dismissal of reporter and editor Benjamin Redd (later managing editor of L'Orient Today), who had been with a group of employees organizing a strike, the paper saw an exodus of much of its remaining staff. The following year, it ceased publication of the print edition but continued to put out news online.

Finally, six months shy of its 70th anniversary, The Daily Star closed for the fourth, but perhaps not the last, time.

In an email, former editor Grimesditch told L’Orient-Today that he was looking for investors to help revive the paper for a fifth time, saying that “even in the current dire circumstances, there are almost certainly a reasonable number of mega-wealthy Lebanese who could keep the paper going, even, for the time being, as a weekly.”

He added that it would likely be an online publication because “freed of the expense of newsprint and presses for a physical product, the cost of maintaining a product is comparatively small.”

Nora Boustany, a former reporter with The Washington Post and a professor of journalism at AUB, found the prospect appealing.

“Lebanon really needs a good English newspaper with in-depth, thorough and thoughtful journalism and commentary,” she said, adding that launching a new incarnation of the paper would be a challenge, but “if someone can step in with huge funding and independent financing, perhaps one day The Daily Star, or a reincarnation of it, can be relaunched.”

Clarification: A previous version of this article stated that the merger between Beyrouth Matin and Le Jour took place in 1964. According to the Kamel Mrowa Foundation's website, the agreement to merge Beyrouth Matin with Le Jour was in 1964. However, the complete relaunch of Le Jour did not occur until 1965.

Additionally, an earlier version of this article cited Kamel Mrowa’s assassination as December 1966. It was actually in May 1966.