A woman approaches the metal gate at the Tahaddi medical center. Although usually a walk-in clinic, due to COVID-19 management measures, the gate is closed and patients must schedule appointments. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

BEIRUT — In the courtyard of a one-story concrete building in the Beirut neighborhood of Hay al-Gharbeh, a handful of people wait patiently behind an iron door to be handed medications or invited in for a consultation.

Written on a piece of paper attached to the bars are the words: “Do not put your hands or face on the door.”

This is the Tahaddi medical center in the time of COVID-19. The small clinic provides free consultations and services to some 500 people every month.

The community it serves, the residents of a rundown area of poorly constructed dwellings that sits below the Sports City Stadium next to the Sabra market and Shatila Palestinian refugee camp, is one of the country’s most deprived.

Around 20 percent of the Lebanese and Syrian patients served by Tahaddi’s clinic are members of the Dom ethnic minority — descendants of nomadic peoples linked to the Roma community in Europe.

On top of living in economic destitution, the Dom also face social stigma and discrimination, and are often referred to in Arabic by a derogatory term.

Increasing needs

Since Lebanon was hit by a crushing economic crisis, exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic, life for the residents of Hay al-Gharbeh has become even more precarious.

Ahlam, born and raised in the area, is a mother of six children. With her husband unable to find work, she struggles to buy the medications she needs to treat her chronic diabetes and high blood pressure.

“I already have to worry about food and caring for my children, and then I have to think about medicine on top of that?” she tells L’Orient Today from a room at the back of the clinic. “It’s a lot.”

“Even before the crisis, our situation was already hopeless,” she continues. “We have nothing.”

Tahaddi is able to provide Ahlam, and many like her, with medications for chronic illnesses that they could not otherwise afford. But over the last year, patients’ needs have increased dramatically, says Dany Daham, a family doctor and Tahaddi’s medical director.

“People are in huge difficulty socio-economically — it is catastrophic,” he says. “This is not new in our community, but it has become much worse.”

The center has around 50 different kinds of acute illness medications on site, available to patients for a small, non-compulsory fee of a few thousand Lebanese pounds.

If a patient requires care that Tahaddi cannot provide, such as surgery or X-rays, medical staff and social workers help them find the relevant clinic and work out how to pay.

“Previously, we’d usually cover between 50 to 70 percent of costs on average,” Daham explains. “Now it’s much closer to 100 percent for many patients. It’s a terrible time.”

Thirty-seven-year-old Dalal came to Lebanon from the Syrian city of Qamishli with her family five years ago. Since her husband suffered a slipped disc in 2019, he has been unable to continue working as a tiler, leaving Dalal the sole provider for the four-member family.

She is able to earn a small living thanks to a sewing machine given to her through Tahaddi’s social support program, but it hardly stretches to cover all her expenses, as the prices of basic goods soar.

“The situation is so terrible now,” she tells L’Orient Today. “I can’t stop crying. I’ll be doing the dishes and I’ll just burst into tears.”

Sahar Abboud bandages a patient’s foot at the Tahaddi medical center. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Sahar Abboud bandages a patient’s foot at the Tahaddi medical center. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Health care providers across the country are struggling to keep up with increasing poverty — now estimated to include more than half the population — and fill the gaps left by a chronically underfunded and poorly managed health system.

According to the Central Administration of Statistics, only just over half of all of Lebanon’s population have some kind of health insurance, leaving the remainder reliant on out-of-pocket spending and limited coverage from the Health Ministry.

Primary health centers are the main point of access for health care for many people, as they offer vital day-to-day health services and are key to fighting non-communicable diseases such as heart disease and diabetes.

However, less than 5 percent of the Health Ministry’s budget is allocated to primary health care, according to a 2020 report by the American University of Beirut’s Knowledge to Policy Center.

“Even before COVID-19 and the economic crisis, Lebanon’s health care system was unable to provide services to everyone,” says Farah Darwiche, a health project manager in Zahle for Swiss aid organization Medair.

Since 2014, Medair has been supporting the Social Affairs Ministry’s social development centers with improvements to primary health care services. Patients coming to the centers typically pay LL3,000 for a consultation, while prescription medications, certain lab tests and scans for pregnant women are provided free of charge.

“People started losing their savings and people living on low incomes are struggling to buy essentials,” Darwiche says. “The private sector is expensive and inaccessible for most.”

A woman sits on a rooftop in the Hay al-Gharbeh neighbourhood. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A woman sits on a rooftop in the Hay al-Gharbeh neighbourhood. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Médecins Sans Frontières, or Doctors Without Borders, runs its own primary health care centers across the country, especially in underserved areas such as the Bekaa Valley. These centers offer services for non-communicable diseases, sexual health and maternity care free of charge.

With the combined health care, political and economic crises, pressure on their services has increased dramatically.

“The demand has increased a lot — not only because of COVID-19, but also due to the economic crisis and political instability,” explains Hammoud Shall, a support project coordinator for MSF in Bekaa.

“We are seeing a big increase in the number of patients, particularly Lebanese people, seeking free health care. We are trying to manage as much as we can, but the needs are increasing day after day.”

In a report published last month, MSF said that the number of patients with non-communicable diseases asking for services in Hermel had doubled between 2019 and 2020. Further south in Arsal, the number of pediatric consultations at MSF’s clinics also saw a twofold increase.

“Many of our patients are new and we are seeing them for the first time,” Shall says.

One of the newer patients at MSF is 77-year-old grandmother Halima, who suffers from atherosclerotic vascular disease — a condition where buildup on artery walls restricts blood flow — and has to take regular anticoagulant medication.

“Without the MSF support, my medicines would cost me LL200,000 per month,” she tells L’Orient Today in a phone call from Arsal, explaining that until recently, she relied on other local clinics and pharmacies that she had to pay herself.

In her household of seven people, income is hard to come by. The only breadwinner, her 45-year-old son, is struggling to earn a living via his job as a taxi driver, as coronavirus restrictions have put a stop to his work at various points.

“We are trying to bring in whatever we can, but if I said we had everything we need, I would be lying,” she says, her voice cracking.

Medicine is not always easy to find, amid shortages in the market due to panic buying and shipment delays caused by the central bank’s alleged failure to process invoices quickly enough.

In an MSF survey of 253 patients with non-communicable diseases conducted in September 2020, nearly 30 percent of people said they had interrupted or rationed their medication either due to financial difficulties or drug shortages.

So far, MSF has been able to secure most of the medications needed by patients, and shortages have been brief. However, this year, Shall explains, they will begin to switch to imports from outside the country arranged via MSF rather than depending on the local market.

Restricted access

For the organizations providing essential medical care in the communities, the coronavirus pandemic has not only brought worries about infection and transmission of the disease. The restrictions on movement and precautionary measures also make delivering the services and ensuring everyone gets the treatment they need difficult.

“COVID-19, and particularly this latest lockdown, has majorly affected our work,” Darwiche says, referring to the round-the-clock curfew from which exemptions are only granted via an online application.

“We need to ask permission to go out and visit people in the field, and while our centers are open, people are accessing them less.”

At the Tahaddi clinic, staff had always been keen to create a welcoming atmosphere, with patients invited to walk in whenever they needed.

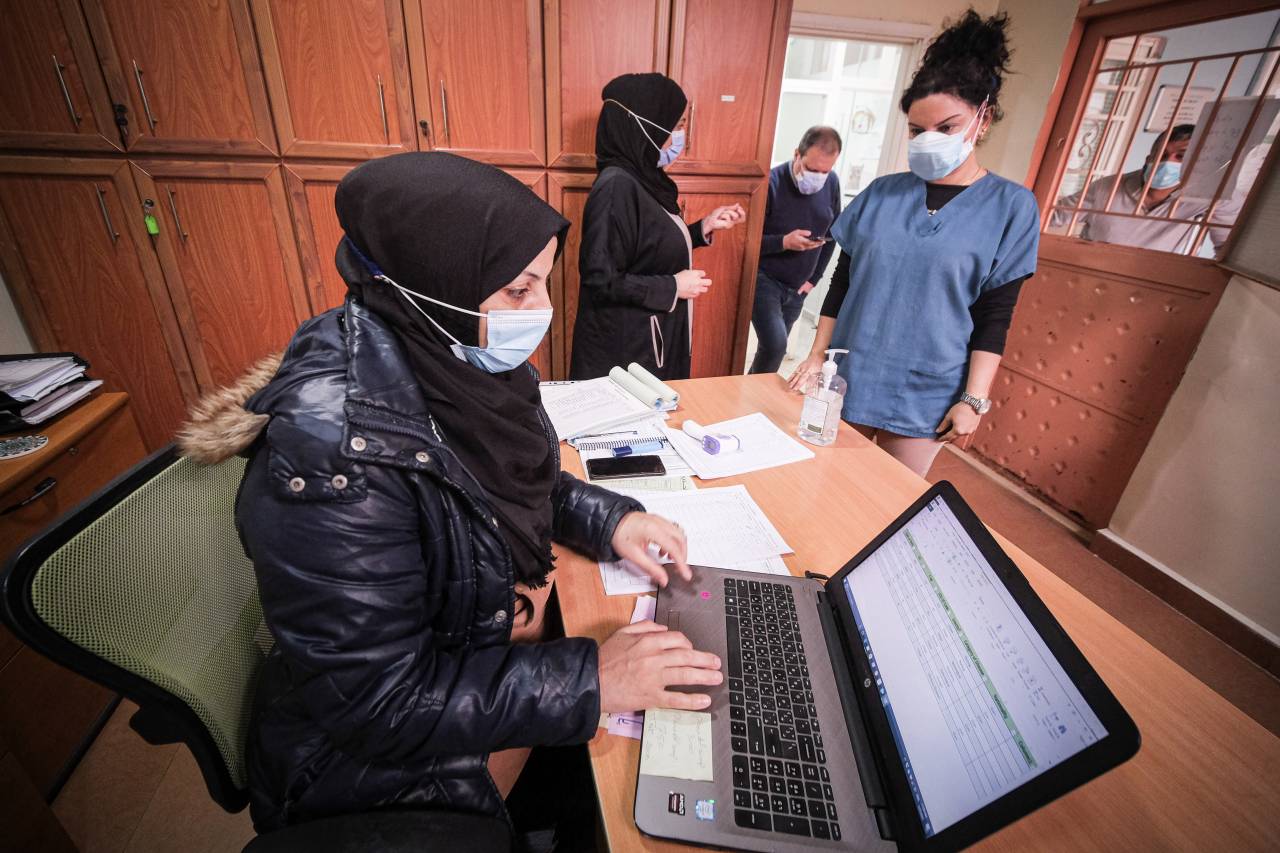

Staff at the Tahaddi medical center work as a man waits outside the door waiting to be admitted. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Staff at the Tahaddi medical center work as a man waits outside the door waiting to be admitted. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

“Our door was always open,” Daham says, pointing at the iron gate at the entrance. “But now it’s closed, and patients have to contact us to make appointments in advance.”

For Sahar Abboud, who has worked as a community nurse at Tahaddi since 2014, the additional restrictions have also put a strain on communication and relationships.

“There is now a barrier between us and the patients,” she says, hands clasped in front of her. “For some of them, we were the only people they could depend on, and suddenly, that closeness disappeared.”

After a long day at the clinic bandaging wounds, administering vaccines and advising patients, Abboud tries to take her mind off things and avoids talking about work. “I try to leave a part of me here,” she says. “If you took it home, you wouldn’t be able to sleep.”

Filling the gaps

With poverty continuing to rise in the absence of adequate and sustainable support from the government and the pandemic likely to stretch on for many more months, the need for free, accessible health care looks set to keep rising.

“We’re not expecting the situation to get any better in the next six months, and we are predicting that there will be a further increase in need,” says Alex Cameron, a project coordinator at Medair, explaining that the organization is currently exploring ways to expand coverage.

“We are trying to fill the gaps as much as we can,” says MSF’s Shall, “but we cannot be everywhere.”