Greek Orthodox Archbishop of Aleppo Boulos Yazigi and Syriac Orthodox Archbishop Youhanna Ibrahim. (Credit: Jaimee Haddad)

On April 17, there were about 15 of them gathered in the conference room on the second floor of the Sofitel in Beirut. Only their clothes distinguished them. Priests and bishops, representing nine Eastern Churches, greeted each other and discussed current events with Lebanese ministers or their delegates over coffee.

Behind the tables which have been set with religious figures on the left, and politicians on the right, are portraits of the two archcbishops of Aleppo, Greek Orthodox Boulos Yazigi and Syriac Orthodox Youhanna Ibrahim, with the inscription: "We do not forget nor remain silent." The speakers, who were invited by the Orthodox Meeting, spoke one after the other on an issue that no longer interested anyone for an hour.

On 22 Apr. 2013, two Syrian religious figures were kidnapped in the province of Aleppo. The incident thunderstruck the Eastern Churches and caused a shockwave beyond Syria. From Pope Francis to Muslim clerics in the region, from Lebanon to Greece and from France to Qatar, the abduction was firmly condemned.

Eleven years later, the investigation into their disappearance has not progressed an inch. Many intermediaries tried to unravel the mystery with the help of half of the region's intelligence services to no avail. Officially, they all hit a dead end. No one knows if they are dead or alive. No one knows who is behind their abduction.

Why them? Why did these two great Eastern Churches representatives disappear without claiming responsibility or demanding a ransom? Why did it happen when the outcome of the Syrian war, which had started two years earlier, was uncertain?

"It's bigger than what we can imagine. We can't talk about it."

Some compare this mystery to the fate of the famous Shiite Imam, founder of the Amal movement, Moussa Sadr, who has been missing since 1978. But this analogy, often used in this case, implies that we will never know the whole story. "It's bigger than what we can imagine. We can't talk about it," confided a Levantine cleric on condition of anonymity.

Indeed, the subject still causes hiccups, sudden muteness and sometimes warnings. "It's such a sensitive issue that it's better not to touch it," the cleric told L'Orient-Le Jour. "It's about people's lives... and yours." For the first time since their disappearance, L'Orient-Le Jour has reconstructed much of the puzzle, though we cannot reach a definitive answer on what happened.

To conduct this unprecedented investigation, we interviewed more than 20 people close to the disappeared bishops: Religious, political, diplomatic, security and intellectual sources. Some accepted our interview request on condition of anonymity. However, the Greek Orthodox and Syriac Orthodox Patriarchates never responded to our requests for over a year.

Prelude

It was the brisk winter of 2013. The battle for Aleppo city raged between loyalist forces positioned to the East and rebel forces to the West. The bodies of dozens of young men were found in mid-January in the Qoueiq River, which runs through the Bustan al-Qasr neighborhood.

The opposition accused the Damascus regime of summary executions against civilians. Like during the Lebanese Civil War, kidnappings by both sides were rampant. The country's main and back roads were dotted with checkpoints. Travel was either interminable at best or dangerous at worst.

"In its modern history, Aleppo has not experienced such critical and painful moments as in recent weeks. Christians have been attacked and kidnapped in a monstrous manner, and their relatives have paid large sums for their release," Archbishop Youhanna Ibrahim told Reuters in September 2012. He hit the nail on the head. A few weeks before his and Boulos Yazigi's disappearance, another kidnapping would set the stage for this story.

It was Feb. 9, 2013. Father Maher Mahfouz was passing through Aleppo to visit his sick mother. Afterwards, he had to return to his Saint George Monastery of the Greek Orthodox in Wadi Nassara, just a few kilometers from the famous Krak des Chevaliers. Armenian-Catholic Priest Michael Kayyal — only 26 years old — had to make his way to Beirut Airport. Along with their Maronite counterpart Charbel Daourat, all three boarded a public bus departing from Aleppo to reach Kafroun, in the Tartus Governorate. Checkpoints were abound. But a few kilometers from Saraqeb, on the highway connecting Aleppo to Damascus then controlled by government forces, the vehicle was stopped by unidentified armed men. They made the first two religious figures, identifiable by their cassocks, get off.

Luckily, Father Charbel was dressed in civilian clothes and escaped the kidnappers' vigilance. "Our brother Michael Kayyal had just celebrated his first year as a priest. He was supposed to fly to Rome that day," Armenian-Catholic Patriarch Raphael Minassian told L'Orient-Le Jour from his office in Beirut in November 2023. "We still don't know who kidnapped them, but I think there is an unknown power, a fifth column. It brings death, but it cannot dominate the spirit," he said evasively.

Armenian-Catholic priest Michael Kayyal and Greek Orthodox Priest Maher Mahfouz. (Credit: The US Department of State)

Armenian-Catholic priest Michael Kayyal and Greek Orthodox Priest Maher Mahfouz. (Credit: The US Department of State)

At the time, the two young clerics' kidnapping almost went unnoticed. The local press barely mentioned it. According to a 2018 report from the Assyrian Monitor for Human Rights entitled "The Good Shepherd" — which recounts the violence and brutality against priests in Syria since the beginning of the civil war —, "informed sources close to the government" claimed they were abducted by an extremist Islamist group. On the other hand, "the surviving priest recounted that these men had a coastal accent," explained Jamil Diarbakerli, executive director of this Sweden-based NGO and the nephew of Youhanna Ibrahim.

Half an hour after the kidnapping, the kidnappers contacted Father Michael's brother and demanded a ransom of 15 million Syrian pounds (over $200,000 at the time) and the release of "15 [unspecified] detainees" from the regime's prisons, claiming no affiliation. The family agreed to pay.

Strange developments followed. The hostage-takers changed their stance: They only wanted the money. For two months, negotiations were conducted by the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate in Damascus, and the ransom eventually dropped to one million pounds. "It was supposedly paid. The Church was looking for someone who could go to opposition territory to retrieve the priests, so Archbishop Youhanna Ibrahim volunteered," Fouad Eliaa, his friend of 30 years and the only survivor of the bishops' kidnapping, told L’Orient-Le Jour.

"This wasn't something new for us. We had done it dozens of times before."

The cleric was no stranger to such endeavors. Leveraging his good relations within the regime and among the opposition, he used his position and diplomatic skills to navigate in this fratricidal struggle. Fouad Eliaa often accompanied him on these kinds of "operations," which involved jumping into a car to retrieve hostages.

"This wasn't something new for us. We had done it dozens of times before. The officers of the Free Syrian Army knew him, and the regime was systematically kept informed," he recounted. The two men have known each other since 1980, the year when this schoolteacher was released from a one-year prison sentence for opposing Hafez al-Assad's regime. "My uncle's fame extended beyond our small Syriac Orthodox community. He was considered the archbishop of all Christians and had very good relations with other religious groups. When the revolution broke out, he didn't sever ties with those who participated; they were his friends," explained Jamil Diarbakerli.

One last photograph

The mission to recover the two priests was scheduled for Monday, April 22, 2013. Archbishop Ibrahim meet with Syrian army officers a day earlier to inform them of the expedition. Less than a 100 kilometers away in Antioch, the Greek Orthodox archbishop Boulos Yazigi concluded his pastoral visit in Turkey and was trying to return to Aleppo. Through a series of circumstances, he would join the convoy.

The meeting was set at the Bab al-Hawa border crossing. Youhanna Ibrahim and his friend Fouad Eliaa were about to leave Aleppo in a small gray car driven by Deacon Fathallah Kaboud. But to cross rebel-held areas safely, the cleric needed solid support. That support came in the form of Abderrahmane Allaf, a lawyer who was then head of the Supreme Judicial Council within the opposition. "We had known each other for a long time. He called me that morning and said, 'I trust only you.' So I brought along my son and an armed man responsible for our protection," recounted the jurist, exiled in Turkey. The kidnappers demanded that the archbishop come alone at the rendezvous point, but Allaf advised against it. They were to all go together. The two cars followed each other to the Turkish border and picked up Bishop Yazigi.

En route, the convoy passed through checkpoints of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) with no issues. "The FSA men respected Youhanna Ibrahim; they welcomed him very warmly," said Allaf. In Sarmada, a city in the Idlib province, Bishop Ibrahim was supposed to meet the kidnappers of the two priests. "They gave us one meeting point, then another. We searched the entire city," remembered the lawyer.

"It was a decoy; no one showed up. They deceived us over the phone, so we decided to return to Aleppo," added Fouad Eliaa. Before parting ways, the group stopped at Allaf's farm in Hawar, a small village in the countryside. The deacon took a final photograph with Abderrahmane Allaf's son's camera. The two bishops smiled.

The last photo taken by deacon and driver Fathallah Kabboud, the day of the kidnapping. Archbishop Youhanna Ibrahim and Archbishop Boulos Yazigi are surrounded by lawyer Abderrahmane Allaf (center), his son (left) and Fouad Eliaa (right). (Credit: Abderrahmane Allaf)

The last photo taken by deacon and driver Fathallah Kabboud, the day of the kidnapping. Archbishop Youhanna Ibrahim and Archbishop Boulos Yazigi are surrounded by lawyer Abderrahmane Allaf (center), his son (left) and Fouad Eliaa (right). (Credit: Abderrahmane Allaf)

The two cars then separated at the FSA checkpoint in Kfar Dael. The archbishops' vehicle had to cross a "no man's land" a few kilometers to Mansoura before reaching the Syrian army checkpoint. On a busy road 500 meters away, a large 4x4 forced them to pull over to the side. Four armed men pointed their assault rifles at the passengers. The assailants had "faces from the East, Chechen or Kyrgyz type," uttered no words and communicated only through gestures.

"They pulled out the deacon, who fled toward the army post. I protested, but they forced me to get out by threatening me with a rifle and grenades. Then they stole the vehicle with the archbishops and sped off towards Kfar Dael," recounted the survivor. Left on the side of the road, the former teacher chose to head back in the opposite direction of the deacon, toward the opposition checkpoint.

After over an hour, he arrived in Hawar, at Allaf's place, who hurried to question the FSA fighters stationed at the Kfar Dael checkpoint. The SUV and the priests' car had arrived in haste before them. "It was the first time our men had seen these guys; they were suspicious," he said.

According to the testimonies he gathered, a scuffle ensued as Archbishop Ibrahim tried to escape from the car. Caught by the collar, he barely had time to throw his ID card out the window, shouting "ya wladi" (my children), addressing the FSA soldiers, before the two vehicles disappeared into the dust.

The deacon was found dead, shot in the forehead less than a kilometer from the abduction site. He was headed towards loyalist positions, between buildings in the al-Rashideen complex. "From the moment he fled until I left the area, I didn't hear any gunfire, so I don't think it was the kidnappers," added Fouad Eliaa.

No leads, no clues

The official Syrian news agency SANA reported the information first, stating that the two bishops fell into the hands of a "terrorist group" (terminology used by the regime to refer to any opposition group) while "conducting humanitarian work." This announcement caused a stir within the Churches in Syria and Lebanon. It devastated the Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch and the East. This was for good reason: Youhanna Yazigi, who had been elected just a few months earlier under the name John X, is Boulos Yazigi's brother. Could it be that he was directly targeted through the kidnapping?

The next day, Pope Francis was one of the first to react, followed by the Orthodox Church of Moscow, the various patriarchs of the Eastern Churches and representatives of Muslim communities in Lebanon.

The head of the Greek Orthodox Church, John X Yazigi, during his enthronement. (Credit: The patriarchy)

The head of the Greek Orthodox Church, John X Yazigi, during his enthronement. (Credit: The patriarchy)

There was a flurry of activity in the offices of Lebanese politicians. Members of Parliament, ministers, the Prime Minister and the President at the time, Michel Sleiman, all denounced the kidnapping, calling for their immediate release. Sleiman immediately contacted his Turkish counterpart, Abdullah Gül. His intelligence services in opposition-held areas must have seen or heard something. "We knocked on every embassy's door, but there were never any leads, no clues about potential sponsors or evidence of their survival or death. The Turks [told] us they [knew] nothing, just like the Syrians. And since [the incident concerned] a small Christian minority, everyone couldn't care less, especially the Westerners," Habib Afrem, president of the Syriac League in Lebanon, still denounces today. For the opposition, this affair couldn't have come at a worse time. The Free Syrian Army, which encompassed a galaxy of rebel factions, was quick to react in the Western press. It asserted its total innocence and vehemently denounced this act.

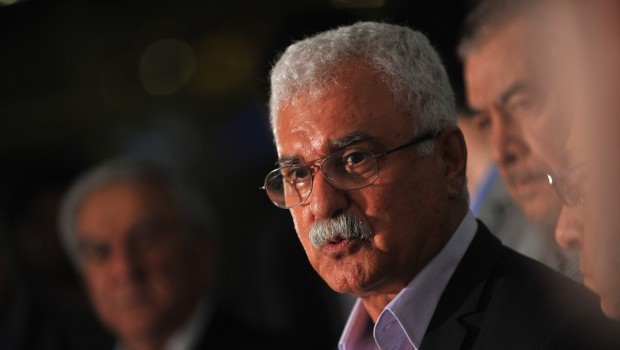

One man's phone never stopped ringing: Syrian, Lebanese, Qatari, Greek and French leaders or personalities took turns on the line. He is a Greek Orthodox from Qatana, a small town in the Damascus suburbs. He had been in exile in Paris for two years. But above all, he is a long-standing opponent of the regime. As president of the Syrian National Council — a political authority formed in September 2011 that at the time brought together around 30 opposition groups — he is the number one political figure in the rebellion. "It was my responsibility to know the truth; I immediately took the matter in [my] hand," Georges Sabra told L’Orient-Le Jour.

The president of the Syrian National Council, Georges Sabra. The photo was taken in Istanbul in July 2013. (Credit: AFP archive photo)

The president of the Syrian National Council, Georges Sabra. The photo was taken in Istanbul in July 2013. (Credit: AFP archive photo)

The confusion led to false leads. The French Christian association L’Œuvre d’Orient announced on April 23 the release of the bishops, claiming they were at the Saint Elijah Church in Aleppo, according to "Christians on the ground." This statement was immediately denied by the Greek Orthodox archdiocese of the city. "We were totally devastated to have announced this incorrect fact, especially since this tragedy had deeply affected us, as we felt it was a vulnerability for all Christian communities," recounted Director of L’Œuvre d’Orient Bishop Pascal Gollnisch. The association was not the only one to jump the gun. "We were clinging to any hope, and we believed in this hypothesis, but after contacts with Qatar and Saudi Arabia, we knew it was false," recalled Georges Sabra, who also announced their swift release.

"We were clinging to any hope."

Abderrahmane Allaf and Fouad Eliaa were the last to have seen the bishops before their disappearance. They combed the region for more than 10 days. "We left no stone unturned. But I quickly realized that it couldn't [have been] someone from our side because the abduction area was too close to the Syrian army," said the lawyer. "The revolutionaries had no interest in committing such a crime. None. I wasn't a representative of the FSA, but this man of faith came to us, and he trusted us," he added.

Through our investigation, several elements helped refine the leads. On the day of the events, the kidnappers released the other two passengers, Fouad Eliaa and Fathallah Kabboud, in the car and only seized the two archbishops. "That shows they had information and clear orders to select their targets," said the president of the Syrian National Council.

Who wanted to make these two men of faith disappear? A radical Islamist group? A gang motivated by money? The regime itself? All possibilities were considered. But the fact that no one ever claimed responsibility for the kidnapping or demanded money or a prisoner exchange murks the true motive of the crime.

Fouad Eliaa during an interview in August 2022. (Credit: SyriaTV)

Fouad Eliaa during an interview in August 2022. (Credit: SyriaTV)

In this affair full of mysteries, one name kept coming up in conversations: Abbas Ibrahim. Just a few days after the abduction, the file landed on the head of General Security's desk at the request of the Greek Orthodox Church. He was the man for the job: An army general, former head of the counter-terrorism and espionage department in the Southern branch of the intelligence services and above all known for playing a leading role in an earlier mediation related to the Syrian crisis.

Five months before the archbishops' abduction, on Nov. 30, 2012, 21 young Lebanese and Palestinian Sunnis from Tripoli and Akkar had joined the rebellion against the regime and were killed in a Syrian army ambush near the town of Tall Kalakh in the province of Homs. Mandated by the Lebanese state, the head of Security negotiated with Damascus the return of the bodies and the extradition of one captive. Abbas Ibrahim is close to Hezbollah, endorsed by Damascus and has connections with Turkish and Qatari intelligence services. He is the preferred interlocutor of Western countries. In this vein, there are many leads that could reveal more clues...