People gather around the carcass of a car used by US-based aid group World Central Kitchen, that was hit by an Israeli strike the previous day in Deir al-Balah in the central Gaza Strip on April 2, 2024. (Credit: AFP)

For Jose Andres, founder of World Central Kitchen, it was cooking alongside Haitians in a camp for those displaced by the 2010 earthquake that taught him the importance of preparing local food when providing for and comforting people in disastrous situations.

The first seven years were focused on sustainable programming, but starting in 2017, in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, WCK established its current model — an on-the-ground disaster relief approach using a network of local chefs to serve thousands of hot, fresh meals based on local recipes.

That’s what his team on the ground in Gaza was doing when the Israeli army targeted them with multiple strikes, killing seven WCK workers on Monday night.

The victims, which included Australian, British, Palestinian, Polish and US-Canadian citizens, had just left a warehouse in Deir al-Balah, central Gaza, where they were unloading around 100 tonnes of food supplies brought into the enclave through the sea corridor.

Those maritime deliveries were a WCK initiative. The organization’s workers were praised for bold strategic moves geared at getting aid into Gaza when they built a makeshift jetty off the coast using building debris from the destruction in southern Gaza. The head contractor for the project even used rubble from his own homes, destroyed in the bombings.

Aerial view shows a World Central Kitchen (WCK) barge loaded with food arriving off Gaza, March 15. (Credit: Reuters/handout from the Israeli army)

Aerial view shows a World Central Kitchen (WCK) barge loaded with food arriving off Gaza, March 15. (Credit: Reuters/handout from the Israeli army)

World Central Kitchen operated 68 “community kitchens,” in Gaza and says it sent more that 1,700 trucks loaded with food and cooking equipment over the last six months of war. WCK is also credited with providing food in northern Gaza, the most heavily destroyed area of the Strip and where UNRWA has often been denied access.

“When people are hungry, send in cooks,” Andres' wife had urged during the relief organization's inception. “Not tomorrow, today.”

Andres is a well-connected celebrity chef and restauranteur, as well as a professor and the founder of the Global Food Institute at George Washington University.

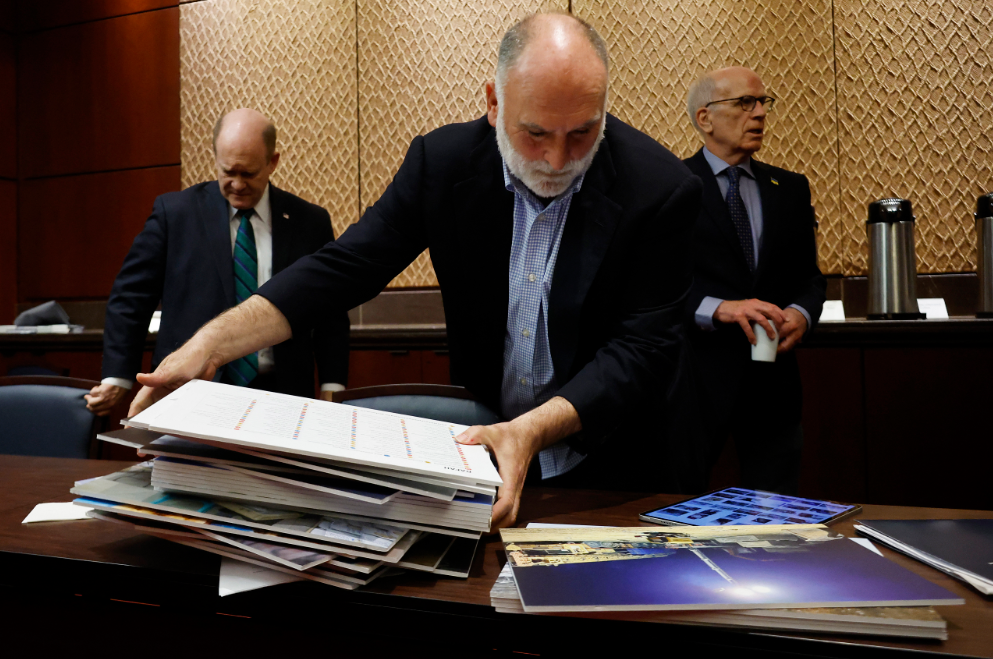

(L-R) Sen. Chris Coons (D-DE), celebrity Chef Jose Andres and Sen. Peter Welch (D-VT) conclude a meeting about getting humanitarian aid to Gaza at the US Capitol on March 14, 2024 in Washington, DC. (Credit: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images via AFP)

(L-R) Sen. Chris Coons (D-DE), celebrity Chef Jose Andres and Sen. Peter Welch (D-VT) conclude a meeting about getting humanitarian aid to Gaza at the US Capitol on March 14, 2024 in Washington, DC. (Credit: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images via AFP)

“When you need medical service, you bring doctors and nurses. When you need the rebuilding of infrastructure, you bring in engineers and architects. And if you have to feed people, you need professional chefs,” Andres wrote on the organization’s website.

In the wake of the killing of its aid workers, WCK announced it was suspending operations in Gaza. At the time of the attack, the convoy was traveling through a “de-conflicted zone,” had communicated its coordinates with the Israeli army, and was driving in clearly marked cars.

Chris Osiek, an open-source intelligence (OSINT) researcher, collaborator with Geoconfirmed, and contributor to Bellingcat, shared satellite imagery of the road where the team was targeted. His analysis, echoed by a New York Times analysis of the same imagery, shows that the cars were hit multiple times and that northernmost and southernmost vehicles are nearly and mile and a half apart.

Following the attacks, several other aid organizations in Gaza also announced they were pausing operations. Among these announcements was one from Anera, which runs the second largest humanitarian operation in Gaza after UNRWA.