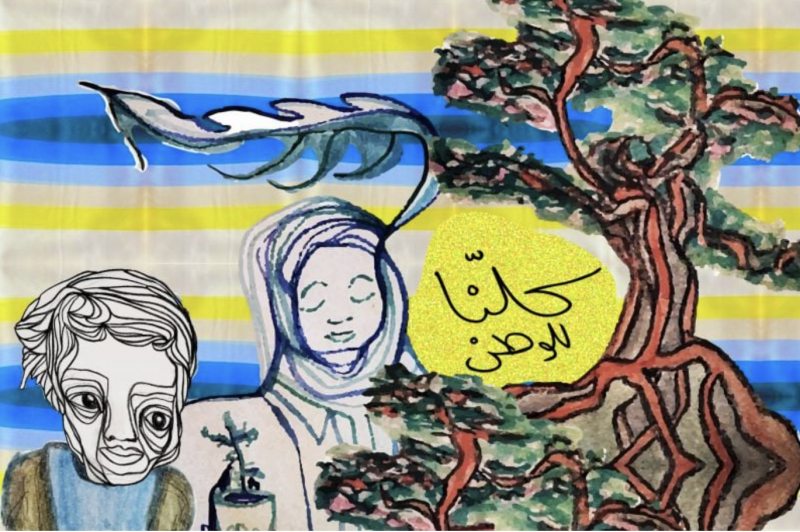

(Credit: Jaimee Lee Haddad)

“You’re not one of us... You’re Syrian.” I was merely 11 years old when my maternal uncle, his expression grave and his voice hushed, unveiled my unexpected hidden identity to me.

He explained that the state held no regard for the Lebanese blood coursing through my veins from my mother’s side, let alone for the Lebanese national anthem, “kuluna lil watan,” I fervently recited every morning in the schoolyard.

Indeed, owing to a peculiar blend of xenophobia, patriarchal norms and confessionalism (a cocktail embodying Lebanon’s myriad challenges), Lebanese women do not have the right to pass on their nationality to their spouses and offspring.

Consequently, like my father before me, I am fated to grow up as a stranger in the only country I have ever called home and dearly cherished.

Throughout my formative years, I gradually grasped that in Lebanon, foreigners are often perceived as undesirable.

We became acutely aware of this reality through encounters with what could be termed “everyday racism” in government offices, at checkpoints, on the streets, in restaurants and even within classrooms.

One memorable instance occurred when a history and geography instructor asserted that Syrians were “unsightly and unclean,” and that they were “only good for construction work.”

Construction work isn’t easy, is it? It’s an inherently respectable profession. At least, that’s what I reassured myself with, attempting to find solace amidst the sudden narrowing of my career prospects.

The war in Syria, which has displaced nearly half of the nation’s population, exacerbated the situation.

With hundreds of thousands of refugees streaming across the eastern border into Lebanon, aggravating the country’s crises, Lebanese animosity toward Syrians intensified.

(Un)fortunately, I found myself becoming accustomed to racial slurs, which gradually lost their sting. Only the occasional “go back to Syria” still manages to provoke me.

Where do you go home when you are already at home?

Did you say ‘courtesy?’

The state also regards us as unwanted guests, despite its guise of issuing “courtesy” residence permits every three years.

As if the indignity of needing approval from the General Security to reside in one’s own country wasn’t enough, these permits afford holders no additional rights whatsoever.

Access to the job market, healthcare, essential services and even certain public parks is encumbered by numerous restrictions imposed on foreigners, including those born to Lebanese mothers.

It’s a “courteous” means of ushering us toward the exit.

Meanwhile, politicians exhibit boundless creativity in justifying this nonsensical predicament.

They meticulously argue that access to nationality must remain severely restricted to prevent any disruption to the delicate confessional balance between Christians and Muslims in Lebanon.

Some even endeavor to convince the populace that granting Lebanese women the right to pass on nationality to their children (or, heaven forbid, to their spouses) would result in an influx of naturalized Palestinian and Syrian (Sunni) refugees, thereby dismantling the famed “Lebanese model.”

The irony is palpable, considering that it was precisely the commitment to human rights — particularly women’s rights — and individual freedoms that rendered this “model” so distinctive in our otherwise conservative region.

Who deserves Lebanese nationality?

Let’s entertain if only briefly, the notion that withholding rights from children born to Lebanese mothers serves to preserve denominational balance, albeit in blatant disregard of the constitution.

If that were the case, then why do children with solely Lebanese fathers — and their mothers, for that matter — automatically receive full citizenship, even if they, like us, are “half” Lebanese? Is their half somehow greater than ours?

Furthermore, there’s the infamous law passed in 2015, permitting the reclaiming of nationality by individuals able to demonstrate Lebanese ancestry, no matter how distant.

Yet, this law — endorsed by Free Patriotic Movement (FPM’s) Gebran Bassil — excludes Lebanese-origin Syrian and Palestinian nationals, effectively granting naturalization solely to individuals, the majority of whom reside in Latin America and have never set foot in Lebanon.

Things don’t end here. At a time when thousands of Lebanese people are being denied their inherent rights, the nation’s citizenship is being seemingly “offered” to an equal, if not greater, number of foreigners through opaque naturalization decrees.

According to numerous civil society organizations, to secure inclusion in one of these elusive decrees, individuals either must “purchase” their spot by paying exorbitant sums of money or “politely request” assistance from a politician.

In 2014 alone, hundreds of Syrians were granted Lebanese nationality through this process, including at least 83 officials from the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, a significant impediment to the repatriation of refugees to their homeland.

Yet, somehow, it is we who are perceived as the threat to the Lebanese model.

The silver lining (if any) is the unanimous acknowledgment, at least on the surface, that the current status quo is unsustainable.

The majority of political groups are proposing to grant Lebanese women the right to transmit nationality to their offspring, albeit with exceptions for those married to Palestinians or Syrians.

Conversely, the more audacious voices advocate for the full restoration of all rights to Lebanese women and their children, without discrimination.

While I’ve harbored doubts about this, my mother has steadfastly assured me that it will come to fruition, citing promises made by the leaders of the party she supports in legislative elections.

“They assured me it would be a gift on Mother’s Day,” she has repeated to me countless times over the years. But, Mom, you’ve misunderstood. It’s not a gift you’re anticipating; it’s a fundamental right.

This article was originally published in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translated by Sahar Ghoussoub. Edited by Yara Malka.