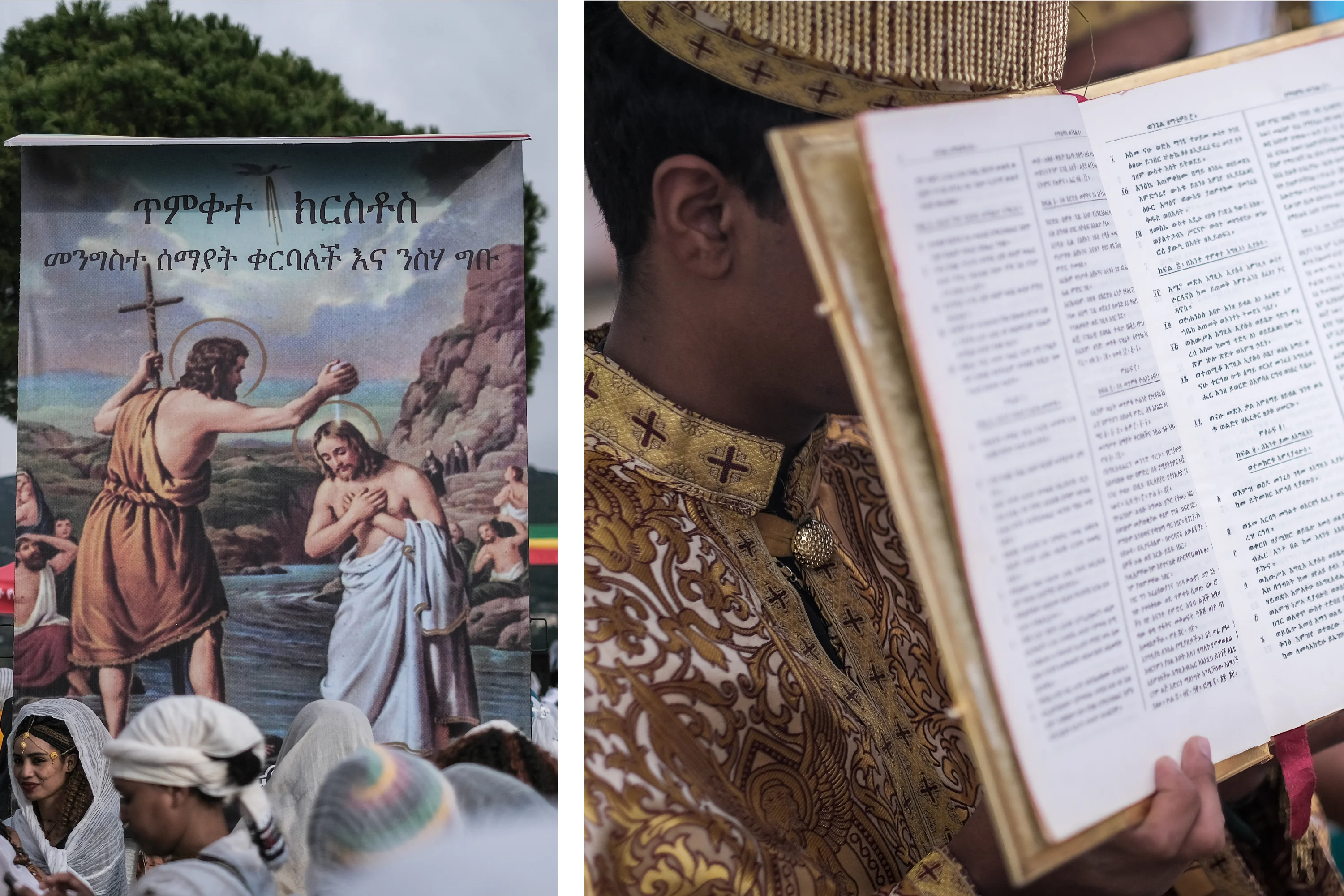

Thousands of Ethiopians gathered at the Mar Mima church in Bentael on Jan. 21, 2024 for Timket. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

A white bus adorned with an Ethiopian flag sped along a winding network of mountainous roads. Dozens of buses and tuk-tuks from Jbeil dropped passengers off, who crowded the ascent toward the Mar Mima church.

Sundays usually follow a similar pattern in the tiny Maronite village of Bentael, where a few dozen families, mostly residing on the coast or in the capital, gather for Mass. However, on this day, the quiet of the town’s hills overlooking a river was filled by chants in Ge'ez or Amharic. Thousands of women in white veils flocked into the church’s square.

On Jan. 21, Timket — a ceremony that lasts three days in Ethiopia, reenacting the baptism of Jesus Christ at the hands of John the Baptist in the waters of the Jordan River — was celebrated. It is one of the most significant festivals for the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, representing over 40 percent of the total population in this East African country. Within the Ethiopian diaspora present in Lebanon (exact numbers unknown due to lack of official counting), they are estimated to be over 60 percent, according to Father Tsegazeab.

An Ethiopian Orthodox woman praying at Timket in Bentael, January 21, 2024. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

An Ethiopian Orthodox woman praying at Timket in Bentael, January 21, 2024. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

In Bentael, the sky hung low over the imposing modern parish with a Roman domus feel, its neatly cut lawn contrasting with the small original stone church a few meters away. Banners in the colors of the Ethiopian flag were hung all around, and in the choir, monks, priests and Orthodox deacons sang Zema (liturgical chants), echoed enthusiastically by the crowd.

Thousands of women, coming from the South, Beirut, Tripoli or the mountains, donned their finest attire for this celebration, more significant to them than the Christmas festivities held two weeks earlier. It is also a time for joyous reunions, a respite from the daily lives of the migrant workers.

Ethiopian Orthodox priests carrying the tabot containing replicas of the tables of the law, during Timket, in Bentael, on Jan. 21, 2024. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

Ethiopian Orthodox priests carrying the tabot containing replicas of the tables of the law, during Timket, in Bentael, on Jan. 21, 2024. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

Lemon throwing

It was 11 a.m., and red carpets were laid out at the church's exit, where groups of celebrants adorned with blue headgear prepared to welcome the grand jubilant procession.

Six monks led the march, carrying on their heads a tabot hidden under layers of shimmering velvet, symbolizing the Ark of the Covenant. This is the chest that, according to the Bible, holds the Tablets of the Law given to Moses on Mount Sinai.

Spiritual singers accompanied the ceremony with praises, preceded by musicians playing the kebero, conical drums or blowing the imbilta (traditional trumpets).

There were women simply covered in white cotton veils from head to toe, immersed in prayer and undistracted.

Then there were others like 20-something Rosa and Samri, their hair blowing in the wind, wearing flashy jewelry, high heels and embroidered dresses in the distinctive vibrant colors of the Amhara region in the northwest. They chatted and took selfies with their friends.

Ethiopian women wearing traditional clothing at Timket, Jan. 21, 2024. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

Ethiopian women wearing traditional clothing at Timket, Jan. 21, 2024. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

Lou*, 24 years old, got her photo taken while tossing a yellow lemon into the air. In addition to fasting, processions and prayers, Timket is also an occasion for meetings and engagements. According to rural tradition, if a man throws a lemon to a woman he fancies and she catches it, she expresses her interest in him.

"But there are hardly any guys here; Ethiopians can be counted on one hand,” laughed Lou. “We're just doing it for fun.”

In the quaint town, transformed into a miniature Ethiopia united by the Orthodox faith, groups size each other up and recognize each other by their language or traditional attire, which varies from one region to another.

"See those women singing together? They're Oromo," said Chayna, 35, proudly displaying the national flag colors. She finds it hard to connect with compatriots from a region that, for the past four years, has been the scene of a rebellion led by the Oromo Liberation Army.

"These people don't want this flag. I lost a few friends because of these issues," she recounted. Yet, Chayna prefers "struggling here than living in a country at war," despite financial precariousness and the specter of conflict with Israel.

The Timket celebration, symbolizing Christ's baptism, on Jan. 21, 2024 in Bentael. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

The Timket celebration, symbolizing Christ's baptism, on Jan. 21, 2024 in Bentael. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

Despite a peace treaty signed in 2022 between the Ethiopian government and Tigray rebels (in the north), ending two years of deadly fratricidal struggles, the country continues to grapple with new episodes of violence in Amhara, where the federal army battles the Fano, a nationalist militia.

"In Lebanon, we put these things aside; there are no disputes. We are very diplomatic people," said Rahel Zegeye, an activist, filmmaker and founder of the NGO Mesewat, dedicated to assisting migrant workers. Last week, she organized a Christmas show and a bazaar allowing women to sell their crochet works.

Mixed marriages

The fact that this context doesn't disappear beyond borders is evident in the chants of "Salam Ethiopia" echoing in the songs sung by the crowd.

"I prayed for this today," confided Mary, a friend of Rahel, accompanied by her 3-year-old daughter, Khouloud,, who wore the same red-embroidered dress as her mother. Originally from Dire Dawa in the East, she feels proud to belong to the great Ethiopian nation.

Rahel Segeye, founder of the NGO Mesewat (left) at the Timket celebration in Bentael, Jan. 21, 2024. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

Rahel Segeye, founder of the NGO Mesewat (left) at the Timket celebration in Bentael, Jan. 21, 2024. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

"Look around you; our differences are our strength," said the young mother. Khouloud grew fidgety. She tightly held a poster of Saint Michael that a stranger lent to her, but she wanted to buy her own.

Her father is Sudanese and Muslim, but she is baptized Orthodox. "I carried her for nine months, took four days to bring her into the world, so he didn't have much choice," joked Mary.

For children like her, born of mixed unions, their connection to the country of origin is complex. Speaking Arabic more often than Ethiopian languages, many of them lack legal papers, according to Rahel, and have limited access to education.

Another issue is the racism that they endure.

"A child at daycare held Khouloud's hand and then let go, thinking her black skin would rub off on him,” Mary said “She's too young to notice, but later, I don't know.”

For some women, it is impossible to return to Ethiopia due to rejection by their relatives who oppose these mixed marriages.

The family of another Mary, originally from Addis Ababa and currently residing in Burj Hammoud, serves as an embodiment of the cultural melting pot that thrives in Lebanon.

Married to a Lebanese Muslim, Mary is determined to pass on her culture and traditions to her son, Charbel, who flitted through the crowd, and her four-month-old Arsemma, peacefully asleep in her baby carrier.

Marie and her 4-month-old daughter Arsemma at the Timket celebration in Bentael on Jan. 21, 2024. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

Marie and her 4-month-old daughter Arsemma at the Timket celebration in Bentael on Jan. 21, 2024. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

The procession continued to the old church where the tabots (a replica of the Tablets of Law,) were brought in, away from prying eyes. It had been over four hours since the ceremony began, and the Mass continued outdoors.

An entire ecosystem evolved around the event. Ali*, who came from Dahye, acted as a salesman for his two photographer companions offering snapshots for $1. Villagers had set up stands, selling drinks and snacks. Although it was a day dedicated to fasting, it was essential to replenish the bus and taxi drivers who had been waiting since morning.

Denise Farah, whose house was visible at the end of the street, set up a saj for manakeesh.

"For three years now, Ethiopians have been celebrating this festival at our place,” said Farah, who is a member of the parish committee “Whether they're Orthodox or Maronite, they're Christians, and that's all that matters to us.”

The Timket celebration, symbolizing Christ's baptism, on Jan. 21, 2024 in Bentael. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

The Timket celebration, symbolizing Christ's baptism, on Jan. 21, 2024 in Bentael. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

Abou Amir maneuvered comfortably among the women, with a white veil around his neck. For thirteen years, he has been transporting Ethiopian women in his taxi, decorated with small green, yellow and red flags.

"I've become their confidant over time,” he said.” And I've lost count of the abuses [of] their employers [that they] tell me about. I'm ashamed of the Lebanese.”

Maya*, from Hamra, attentively followed the church service. "It's the only time of the year when the girl who works for me goes out, so I accompany her," she said. "I tell her to go out on Sundays, but she does not want to. I trust her," said Maya, the employer, seemingly oblivious to the gravity of her statements "She's somewhere in the crowd," she said, giving the impression that she did not wish her employee to be interviewed.

Many Lebanese employers still use the Kafala system, an outdated sponsorship system that places domestic workers under the control of their guarantor.

"We have problems with bosses who don't let these women go out,” said Father Tsegazeab.” They left their country, don't see it for years; at least let them go pray.”

The ritual baptism celebration was about to begin. A large plastic blue pool filled with water was blessed by the celebrants, and the crowd gathered around with raised hands.

Father Tsegazeab seized a pressure washer to spray the assembly. Children cried in the arms of their laughing parents. Drenched women exited the ranks, laughing, immortalizing the moment on their mobile phones.

Father Tsegazeab sprinkling holy water on the crowd at Timket in Bentael, Jan. 21, 2024. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

Father Tsegazeab sprinkling holy water on the crowd at Timket in Bentael, Jan. 21, 2024. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient-Le Jour)

The procession resumed, and the tabots returned to the church in a crescendo.

It was past 3 p.m. when the crowd dispersed, heading back to their daily lives in Lebanon.

*The first names have been changed at the request of the parties concerned.

This article was originally published in L'Orient-Le Jour.