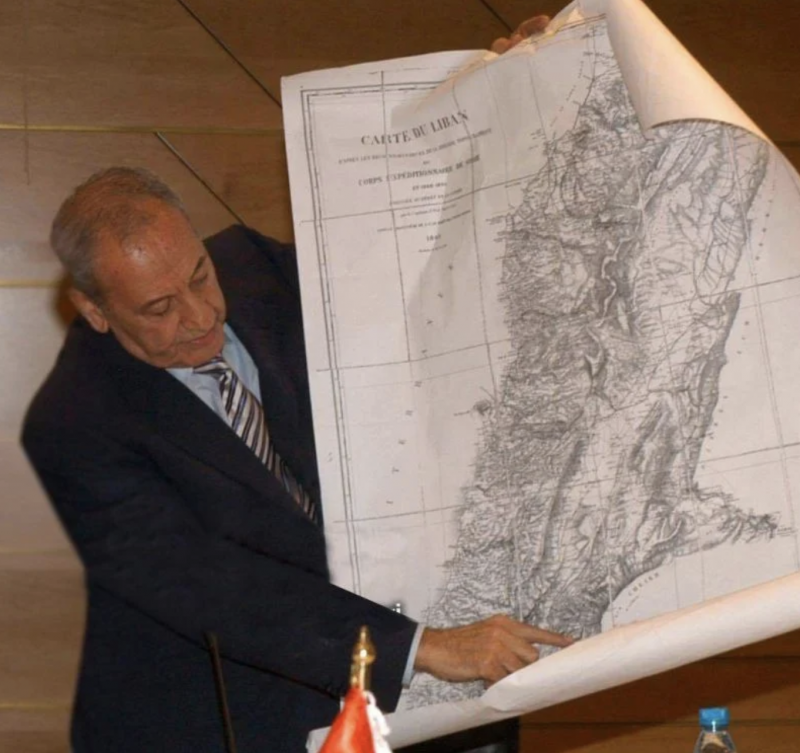

Speaker of Parliament Nabih Berri points to Shebaa Farms on a huge map of Lebanon during the National Dialogue Conference held in March 2006. (Credit: Berri's Facebook page)

On May 25, 2000, Israel withdrew from south Lebanon after more than 22 years of occupation. It was then that Lebanon discovered a piece of forgotten territory: The Shebaa Farms.

Although the majority of Lebanese people were unaware of this tiny piece’s existence in the Golan Heights, which the international community considers Syrian and occupied by Israel since 1967. Shebaa Farms has suddenly become a territorial claim by Beirut.

This 14 kilometers long and two kilometers wide segment, situated to the south of the Sunni-majority village of Shebaa, in Hasbaya district, has provided Hezbollah with a golden pretext to keep its arsenal to “liberate what remains [occupied] of the Lebanese territory.”

24 years later, Shebaa Farms are back in the news. This is because they are now at the heart of the post-Oct. 7 war negotiations.

For US envoy Amos Hochstein, defusing the escalation between Hezbollah and Israel requires a border demarcation agreement, which Beirut believes must include, among other things, an Israeli withdrawal from that area.

“We have the opportunity to liberate all our territory, including Shebaa Farms,” said Hezbollah’s Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah in early January. But how did Shebaa Farms become “our territory”?

To answer this question, we need — as is often the case — to go back to the origins of Greater Lebanon. When the French drew the country’s borders in 1920, they did so on the basis of not very precise maps drawn in 1862 by the topographical brigade of the Expedition Corps in Syria, which had intervened in Mount Lebanon (then Ottoman territory) to put an end to sectarian clashes between the Druze and Maronites.

Some 60 years later, Syria and Lebanon came under French mandate. But their approximate borders were not demarcated, as the French saw no urgent need to do so.

The Paulet-Newcombe agreement between Paris and London in 1923 only delimited the international border between Lebanon and Palestine, which was placed under British mandate.

As a result, the Lebanon-Syria border was lined with gray areas. Shebaa Farms, located between the village of Ghajar to the west, Jabal Hawarta (one of Mount Hermon’s summits) to the east and the Wadi Assal river to the south, are a stark illustration of this.

A “loaded withdrawal”?

According to US historian Asher Kaufman, the maps of the time seemed to place the territory in question, which is made up of 14 farms, in Syria. Nevertheless, they were de facto under Lebanese sovereignty.

In 1920, for example, when the villagers of Shebaa cut down trees in the farms to pay a fine imposed by the French high commissioner, it was the governor of the Lebanese Hasbaya governorate (and not of the Syrian Qunaitra governorate) who intervened, considering that the felling of trees in this area was under his jurisdiction.

Pierre Bart, an administrative consul to the French administration in south Lebanon, concluded that the river Wadi Assal (now renamed Nahel Sion by Israel) was the actual border between the two republics.

“This border anomaly is likely to create problems,” said Bernoville (first name unknown), a French special services officer stationed in Damascus, in 1939, and stressed the importance of resolving this issue.

Since Lebanon’s independence in 1943 and Syria’s in 1946, however, no serious initiative has been taken to resolve the dispute, perhaps because the status quo suits both countries, but also the smugglers.

It was in 1958 that Lebanon largely lost its control over Shebaa Farms. President Camille Chamoun’s pro-Western stance soured relations with the United Arab Republic (brief union between Syria and Egypt, dominated by the latter), whose army then moved into the area, amid a total indifference from the authorities and the media in Beirut.

Nine years later, Israel annexed the Syrian Golan (including the Shebaa Farms) following a lightning offensive. Not a word was heard from the Lebanese side then either.

Shebaa Farms were not remembered until 2000, when Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak unilaterally announced the end of the occupation of south Lebanon, in accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 425.

Although this had been one of his key promises in his campaign during the 1999 legislative elections (the last to be won by the left), the announcement still came as a surprise in Beirut, where the pro-Hezbollah circles, fearful of losing the status of “resistance,” denounced a “loaded withdrawal.”

But when the Israeli withdrawal became an undeniable reality — verified even by the UN — Lebanon pointed to its sovereignty over Shebaa Farms and considered that this piece of territory is Lebanese — not Syrian — and still under occupation.

At the same time, Syrian Foreign Affairs Minister Farouk Sharaa, stated in a phone call with the then Lebanese Prime Minister, Salim Hoss, that his country, which was exercising trusteeship over Lebanon at the time, considered that Shebaa Farms were Lebanese.

‘Mappers by parachute’

In fact, they only do so when it suits Syria and its ally Hassan Nasrallah. Damascus refuses to give legal force to its position by transmitting it in writing to the UN, arguing that this would first require a demarcation agreement with Beirut and that this was not possible as long as Israel occupies the Golan Heights.

“How can Syria demarcate its border in an occupied territory?” asked former Syrian Foreign Minister Walid al-Moallem in 2006. “Should we send mappers there by parachute?”

Damascus also refuses the (rare) Lebanese attempts to negotiate a demarcation of the entire shared border.

Moreover, in private, Syrian officials repeat that the farms are Syrian and are an integral part of the occupied Golan Heights, which Israel must return in accordance with UN Council Resolution 242 (on the territories occupied in 1967).

In his book on the secret peace negotiations between Israel and Syria in 2011, former US diplomat Frederic Hof recounted that President Bashar al-Assad assured him that Shebaa Farms were Syrian, and that their return under Syrian control, like the rest of the Golan Heights, was a precondition for any peace agreement.

Shebaa Farms were back in the spotlight in 2006. After the end of the July war between Israel and Hezbollah, Beirut campaigned to have the territory mentioned in UN Security Council Resolution 1701.

The latter “takes note” of the seven-point plan of Fouad Siniora’ s government, which provides for an Israeli withdrawal from the area and the demarcation of the land border with Syria and Israel.

All this has remained a dead letter. All the more so as the Lebanese identity of the farms is disputed even within Lebanon. In 2019, Druze leader Walid Joumblatt stated in an interview with Russia Today that the farms do not belong to Lebanon.

“After the liberation of south Lebanon in 2000, the Lebanese cartography was changed by the authorities in Beirut, in collaboration with the Syrians,” he said.

But just when it was thought that the issue had been buried, Operation al-Aqsa Flood revived it. The international community called on the Lebanese to implement UN Security Council Resolution 1701 more strictly, which calls for Hezbollah to be kept away from the border in exchange for Israel respecting Lebanese sovereignty.

Beirut and Hezbollah called for the Israeli withdrawal from Shebaa Farms and the 13 disputed points on the southern border.

Some observers believe this withdrawal would deprive Hezbollah of the main argument it uses to keep its arsenal. For others, the party will surely find a new excuse so as not to make any concessions.

This article was originally published in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translated by Joelle El Khoury.