Hussein Madi (1938-2024), the artist with the eternal beret. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist)

Proudly donning a beret for a long time, he cultivated a physical resemblance with Picasso.

He had the same dark, watchful gaze, decorticating the world, people and nature. He had the same mysterious character and the same intense presence.

But his art, despite the geometric similarities with that of the Spanish artist, was infused with a calligraphy and spirituality emblematic of Eastern culture, of which he was one of the most prestigious representatives.

Born in 1938 in Shebaa, at the foot of Mount Hermon, Madi was always intrinsically associated with nature, which he has never treated like a landscape painter. Instead, he drew from nature the elements that made his work unique.

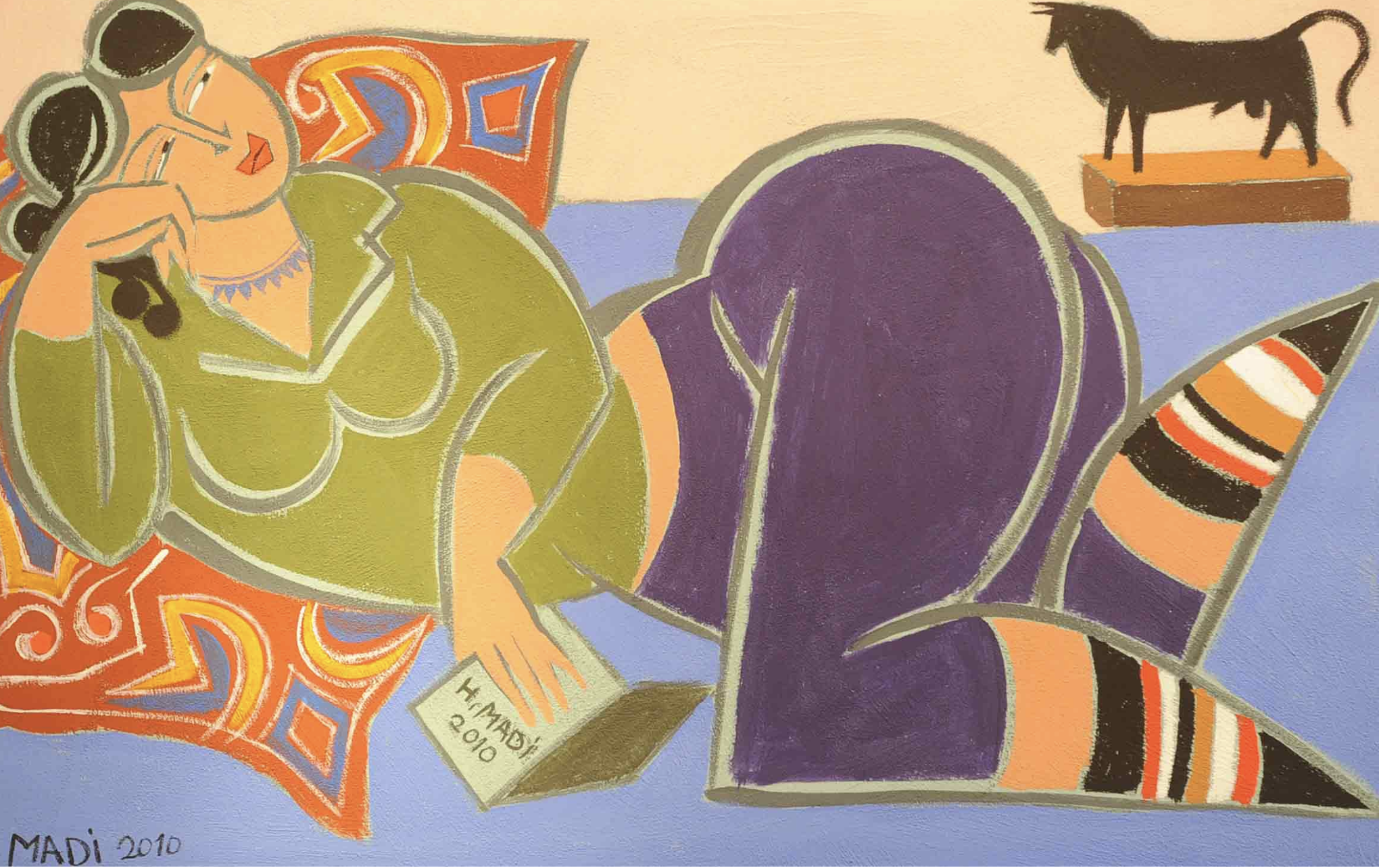

Birds, horses, bulls and cats were his leitmotif, in parallel with the silhouettes of “Woman,” whom he celebrated in his paintings and sculptures, considering them as “the most beautiful forms in the world, the most perfect creation.”

Women, one of the artist's favorite subjects. (Credit: Michel Sayegh)

Women, one of the artist's favorite subjects. (Credit: Michel Sayegh)

An artist at heart, Madi “at the age of four, fell in love with a drawing of an apple on a piece of paper,” he told L’Orient-Le Jour in 1999. From then on, he chose to “live in the beauty and mystery of arts.”

After his painting studies at the Lebanese Academy of Fine Arts (ALBA), and working as a caricaturist for Kifah and L’Illustration, he flew to Rome in 1964 to complete his studies at the Accademia di Belle Arti. The initial plan was for him to stay for just two months, to learn about the craft of fresco and mosaic-making, but his stay lasted 22 years.

His years in Italy

During his two decades-long stay in Italy, he frequented the entire art scene, and made a name for himself through exhibitions in numerous art galleries in Rome, Milan, Verona, London, Paris, Baghdad, Alexandria and Tokyo.

In 1986, at a time when his career was on track in Italy, he couldn’t bear to live in tranquility while his family went through war. The bittersweet attachment to the homeland pushed him to return to Beirut for good.

Madi's art, exhibited many times at Galerie Aida Cherfane. (Credit: Michel Sayegh)

Madi's art, exhibited many times at Galerie Aida Cherfane. (Credit: Michel Sayegh)

There, as a great believer in freedom, he chose a studio overlooking the sea. Despite life difficulties in Lebanon, he never regretted coming back to the country, said Mohamad al-Rawas, a loyal friend of his since the 1970s.

In Lebanon, where his talent was recognized — he was awarded the Sursock Museum grand prize of painting in Beirut in 1965 — Madi further developed his approach to sculpture, using seamless folded forms. He taught this discipline at the Lebanese University’s Institute of Fine Arts.

“It’s a difficult job, because a good sculptor must be a good draughtsman who reproduces the dimensions correctly, he must also have a three-dimensional vision and finally he must choose the right material for the topic,” he said.

This was often iron, a material that matches his strong personality and his inflexibility as a high priest of arts. “This intransigence defined him and commanded respect,” said Rawas.

Aiida Sherfan, who, after Samia Toutounji, was his exclusive gallerist from 2000 to 2019, remembers Madi’s first exhibition in her gallery in Antelias. “He chose to present purely figurative canvases that were totally different from his known style. This raised a lot of questions. He explained to me that he had done this deliberately in order to ‘reinvigorate the practice of drawing among abstract artists, a key basis of any quality art.’”

‘Madi was simple but complicated’

He was hedonistic and circumspect, brusque and patient, sharp and poetic, detached from material contingencies and highly ambitious at the same time. His work was like him, based on a subtle balance of forces: A delicate combination of shapes and colors, structure and sensitivity. The birds, bulls and women he depicted in his work are a blend of extremely radical geometric plan and elegant curves.

Still life (2011) by Hussein Madi. (Credit: Michel Sayegh)

Still life (2011) by Hussein Madi. (Credit: Michel Sayegh)

Closely related to his sculptures, his paintings had the same vocabulary, with the addition of colors. This often calligraphic inspiration is combined with the multiplication of the subject. The repetition is there on purpose, “It is a way to honor the creator,” he said.

“He was an incredibly productive artist,” said Sherfan. “He worked non-stop, and his practice was truly skillful, ranging from drawing to ceramics, painting, sculpture, engraving and lithography.”

“‘I’m married to the arts,’ this great loner would often say to me. He was generous and impulsive. He supported me when I was starting out as a gallery owner, at a time when everyone was discouraging me. He impressed people with his umbrageous attitude, his fits of anger, but for those who really knew him, he had the heart of a child,” said Sherfan who has a deep sense of gratitude for their collaboration.

Bahjat Eldarwish, one of Madi’s greatest collectors and a close friend for the past 20 years, agreed. “Madi devoted himself totally to arts, sacrificing his personal life and giving up plans to marry so as not to hinder his creativity. The remarkable thing about his talent was that, using a few elements that he had chosen, such as a woman, a leaf from a tree, a bull, a bird, etc., he would tirelessly reinvent himself on canvas, in sculpture, in 3D wooden paintings. In short, Madi was both simple and complicated. He influenced a whole generation of artists and left an extraordinary legacy that we absolutely must preserve.”

A "Donquichottesque" sculpture by Hussein Madi. (Credit: Michel Sayegh)

A "Donquichottesque" sculpture by Hussein Madi. (Credit: Michel Sayegh)

Although his works are already in major public collections in Dubai, Rio de Janeiro and London (British Museum), “he deserves to have a museum dedicated exclusively to him.”

The artist told L’Orient-Le Jour, “I work in all honesty, not to live but to leave a trace of my arts.”

This article was originally published in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translated by Joelle El Khoury.