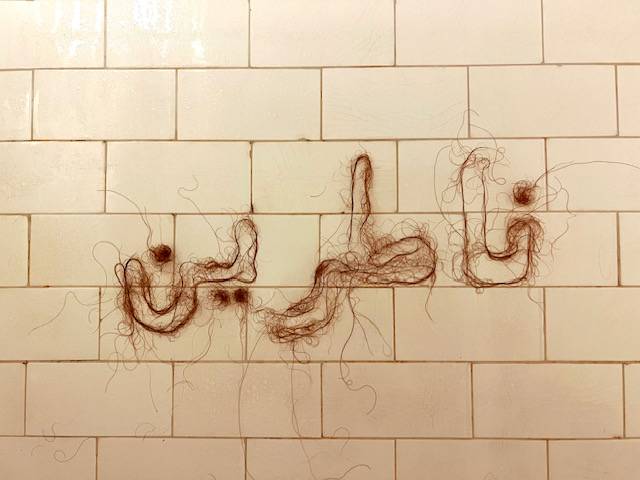

“Natreen," sketched with the artist’s wild fallen hair strands on the humid bathroom tiles, Oct. 24, 2023. (Credit: Lama Sfeir)

Lama Sfeir

After the economic collapse with the currency shortage in 2019 and the Beirut blast in August of 2020, comes the anxiety of whether or not the fighting in southern Lebanon will expand throughout the country—a real catastrophe for which we are not prepared. Those who can afford to travel have taken their families abroad as a contingency plan, while others are storing staple goods for potentially darker days. Parents are on alert to get their kids from school in the case of a surge; everyone is waiting for politicians' speeches—hoping they will make the right decisions for the people of Lebanon.

We grew up with these worries in this part of the world. We are compelled to exchange years of distress for dual citizenship—not in order to procure a desired lifestyle, but to reach safety. The luxury of packing and leaving in an emergency is not given to everyone; many Lebanese cannot get a visa approved on their passports.

Born in Beirut in 1980, I have witnessed four wars and dozens of targeted explosions; two of which I missed by a matter of seconds. In the aftermath, my dreams were put on hold for reasons I had no control over.

Now I live in New York, and I call my loved ones to ask how they’re doing and offer support during their disquiet. They all have the same answer, “Natreen,” which means “we are waiting” in Arabic. I have come to the realization that our culture has been suspended in a state of anticipation—under the shadow of the next catastrophe.

We are waiting for the economic crises to pass, waiting for the war to end, waiting for our neighbors to make peace, waiting for the electricity to come, for medication to become available, for the opportune moment to open a business, for schools to reopen, for the currency to stabilize, for expatriates to improve the economy during holidays, for visas to be approved, for passports to be renewed, for the elections, for a politician’s promises and now, waiting to see if the conflict will stretch all over the country.

Our lives are lived on hold. We have acquired the skill of building dreams in transit, on an unstable infrastructure, hoping that the rubble will eventually settle. We adapt to any situation, outsmart the system, generate our own power, adjust to a president-free system, accept the corrupt politicians not because we are apathetic, but because we crave stability. We are pulled under by a riptide of uncertainty; holding our breaths, we tread, waiting to surface for air and get a break.

Waiting is not a temporary state; it’s our reality—we are conditioned by it. Observing what is happening in the region today, I am reminded that we have all been suffering from that same condition.

I left Beirut in 2010 following a series of bombings that started in 2004—one of which was the assassination of Prime Minister Rafik Hariri. Politicians and journalists were targeted in public places; no safe areas remained. My friends and I constructed an illusion of safety, driving on previously bombed routes and visiting blasted shopping malls because we doubted they would be attacked again. I waited for the season of destruction to pass; it never did.

I was perpetually saddened to observe close friends and family members quarreling over political views and accusations, most of which were of a speculative nature surrounding the identity of the attackers. I sat to the side, watching them break deep bonds of friendship because of affiliations to sects and political parties; ideological ties had become stronger than loyalty to loved ones—a model of what is happening in the entire world today.

As an artist, my plans were at odds with my environment. I hoped to address matters of identity and belonging to the area, stand up against racism—call attention to the cultural differences and discrimination of foreigners. My intention was to inspire tolerance and positive change—issues that have been stagnant in our unsettled region.

Whenever I discussed these subjects in social settings, I was hushed as the conversation changed course to praise political leaders whose plans would cultivate hate for other parties and create more division. My outspoken views were overshadowed by corrupt politicians playing their parts on every screen. I relished watching their speeches on mute and observing their body language, silencing their voices the same way they silenced mine. These politicians had impoverished our families, demolished our homes, crashed our dreams and assassinated our fellow citizens.

When I left Beirut for the United States more than a decade ago, I promised myself that the waiting game would be over for me. I was determined to never look back.

Reflecting on the state of the world today—observing the hatred, anger and finger-pointing that thrives on social media—brings me back to the reasons why I left my country. Back then, chaos was on a smaller level and more contained; today it's growing exponentially on a global magnitude. Where do I go now?

Today, I am waiting for things to resolve, in the hope that one day I will retire in that perplexing place, my home.

Lama Sfeir is an interdisciplinary designer and artist whose work documents her personal artistic journey and explores themes of identity and self-acceptance between two continents.

As a child, Lama longed to free herself from the painful taming of her hair wrought by her mother. Her big hair became a source of shame and belittlement in her environment, hindering an acceptance of her true self. Lama has been collecting her fallen strands from the bathtub for over a decade, using them as a sticky pigment on the shower wall to create recurrent social complaints, powerful statements that challenge deeply rooted stereotypes, sketches and arabesques — a representation of an unspoken part of her identity and playful exploration. Her once-distressing hair, carrier of traumatic events and stories, is transformed into a medium for personal investigation.

Her work has recently been featured in a collective exhibition at Galerie Janine Rubeiz in Beirut.