A plate of hummus bl-tahini. (Credit: Joao Sousa/L'Orient Today)

L’Orient Today’s culinary heritage series explores the stories behind Lebanon’s favorite foods. Food tells us the story of our heritage, which is preserved through the recipes we so often enjoy. Every day we (often unknowingly) consume history — both figuratively and literally. Recipes are a living, traveling thing, retaining and losing ingredients along the way. But more than that, the food we eat tells us a lot about ourselves. It reveals us, sometimes unwillingly, in a “tell me what you eat and I'll tell you what you believe,” kind of way. From home cooked comforts to street food favorites old and new, we offer you this sense-indulging ride through Lebanon’s rich and flavorful culinary history. Enjoy, and of course, sa7tein.

In this installment: hummus. Nothing rouses nationalistic sentiment quite like it. But where does it come from? And who does it belong to?

TRIPOLI — Al-Dannoun is a specialty hummus joint nestled in a calm alley behind Tripoli’s buzzing commercial Azmi Street. Beyond the restaurant’s iron-latticed entrance, guests are first greeted by the strong aroma of boiled chickpeas.

Inside, nothing sits still. Waiters run plates of hummus, foul, fatteh and the like to hungry customers. Tasty spreads are quickly devoured, and plates are wiped clean with fresh, oven-fired flatbread, always accompanied by a classic plate of pickles, olives and vegetables. People rotate, orders are announced, and takeout is packed synchronously.

The restaurant’s owner is Bilal Abdul-Hadi, a published author and linguistics professor at the Lebanese University set to retire this year.

Abdul-Hadi, who teaches Chinese in his spare time, adores the restaurant his father opened in 1949.

His food-loving father, who was orphaned at the age of three and worked since childhood, first opened al-Dannoun near the Abu Ali River in Tripoli, where it remained until the river flooded in 1954, taking the shop with it. The family has maintained the current location since 1959.

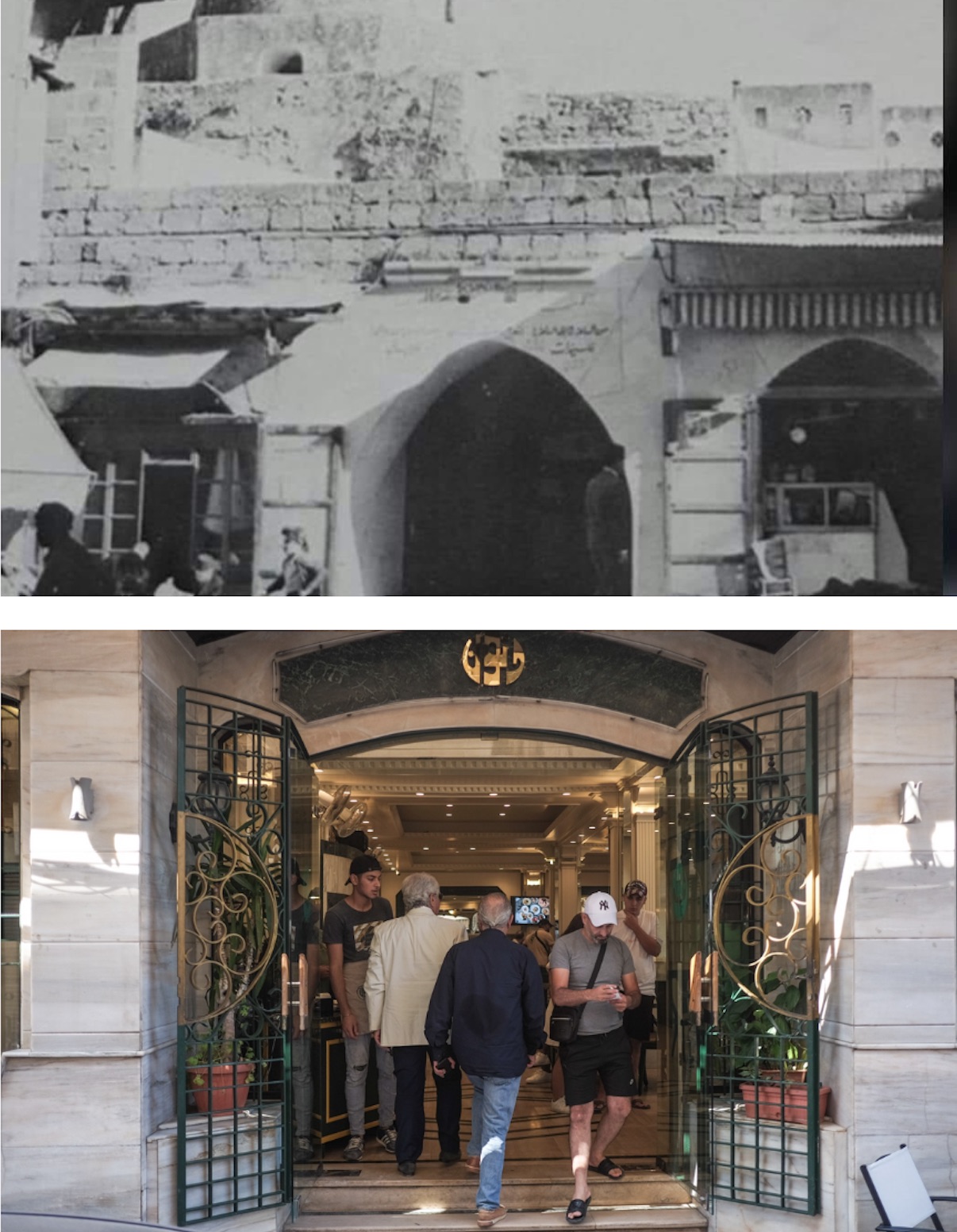

(Above) al-Dannoun's location in Tripoli's old souk, where it was briefly located between 1954-1958, after the first restaurant was destroyed by flooding; (Below) al-Dannoun's current location near Azmi Street in 2023. (Credit: Joao Sousa/L'Orient Today).

(Above) al-Dannoun's location in Tripoli's old souk, where it was briefly located between 1954-1958, after the first restaurant was destroyed by flooding; (Below) al-Dannoun's current location near Azmi Street in 2023. (Credit: Joao Sousa/L'Orient Today).

Serving traditional breakfast and brunch, al-Dannoun is one of the city's most famous “foul and hummus” spots. And there’s good reason for that. It is convenient, affordable and, ultimately, delicious.

Above all else on the menu, al-Dannoun’s hummus is the show stealer.

Global foodways

Hummus bl-tahini is a core staple of any Levantine mezza spread today.

Made of smoothly blended chickpeas, with tahini (sesame seed paste), lemon, garlic, and olive oil, the dish is synonymous with its main ingredient and is known simply as “hummus,”’ Arabic for chickpeas.

The chickpea, which has now spread across the globe, originated in the Mediterranean basin, likely between present-day Turkey and Syria.

It is one of the region’s essential crops and has been an ingredient of local cuisine for more than 4,000 years.

The earliest mention of the current hummus recipe known to Lebanon dates to 1885, in the cookbook Tizkarat al-Khawatin wa-Ustaz al-Tabbakhin (A Manual for Ladies and the Master Chef), by Khalil Sarkis.

But even before that, a recipe for “hummus kassa,” a similar dish — albeit with vinegar and more spices — can be found in the 10th-century Baghdadi cookbook Kitab al-Tabikh.

(Credit: Joao Sousa/ L'Orient Today)

(Credit: Joao Sousa/ L'Orient Today)

Hummus likely started as an urban dish for the elite, before becoming a popular fast food throughout the Levant’s bustling urban centers, and finally a home recipe. Workers would eat it in the morning to fuel a long day of labor, hence its reputation as a breakfast food.

Ironically, Lebanon imports most of its chickpeas from Canada, America, Turkey, and Mexico.

“We use Canadian chickpeas here,” Abdul-Hadi divulges.

Canada is one of the world’s largest chickpea producers, with 96 percent of their farms in Saskatchewan, the place where, coincidentally, this author spent her childhood.

”We [Lebanon] don’t have self-sufficiency in anything. We even import lentils in Lebanon. I remember long ago they used to plant lentils here in Tripoli and in Akkar. Now no one plants it because it's all imported. Even burghul. It all used to be made here,” Abdul-Hadi says.

Hummus Wars

Although Lebanese hummus is — apparently — Canadian it remains the dish most capable of rousing nationalistic sentiment in the country’s culinary repertoire.

When Israel broke the Guinness World Record for the largest hummus serving in 2008, after a group of chefs in Jerusalem prepared a 400-kg bowl, Lebanon would not let them have the final word.

The event started a (culinary) war. At the time, the Israeli Army’s radio jokingly called it the “third Lebanon war,” just two years after the (very real) 2006 war.

Lebanon prepared to sue Israel shortly after and, in 2009, retaliated with a 2,050-kg hummus bowl.

Lebanon's first record-breaking hummus bowl in 2009. (Credit: Ramzi Haidar/AFP-Getty Images)

Lebanon's first record-breaking hummus bowl in 2009. (Credit: Ramzi Haidar/AFP-Getty Images)

It did not end there.

In 2010, Israel one-upped Lebanon with a 4,070-kg bowl, prepared by 50 chefs in the Arab village of Abu Ghosh.

At the time, Jawdat Ibrahim, the Palestinian-Israeli hummus restaurant owner who led the initiative, proudly emphasized that Abu Ghosh’s team used all local ingredients and criticized Lebanon for using chickpeas imported from Turkey.

Ibrahim dedicated the victory to “the whole village, the whole country, the whole people.”

He also addressed the Arab world: “I am saying to people in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Egypt: I know the situation is complicated because there is no peace, but I would love it to happen one day, that we can cook one plate of hummus — about 10,000 tons — to share with the whole Middle East.”

Now a popular food among Israelis, it was often Mizrahi (North African and Middle Eastern) Jews and Palestinians like Ibrahim who introduced local Arab recipes to consumers.

On May 9, 2010, five months after Israel had set the world record, Lebanon shot back with a hummus serving twice as large. It weighed in at a whopping 10,452 kilos (reflecting the size of Lebanon, which is 10,452 km²) and was presented in a massive traditional fakhar (clay) bowl — quite literally a swimming pool of hummus.

Led by the Association of Lebanese Industrialists, the initiative was carried out in collaboration with TV Chef Ramzi Choueiri, 50 other chefs and 300 culinary students at Al-Kafaàt University.

Lebanon has held the Guinness Record since and considers itself the victor of the hummus war.

“We worked a lot to mainstream the plate of ‘hummus bl-tahini’ as a Lebanese food in the same way that champagne is named after the region of Champagne in France. So no one else can use the name,” says Georges Nasroui, vice president of the Association of Lebanese Industrialists.

The association even appealed to the Economy Ministry for support in their copyright case to the EU.

“You know. They didn’t stand beside us,” he says.

“Today Israel has a bigger industry than us because it has a government behind it,” Nasroui sighed.

A dream

“Humans have an emotional attachment to food. It’s not just a biological need,” Abdul-Hadi says.

Back in Tripoli, al-Dannoun is as busy as ever.

Often overlooked in the haste to eat is the Khalil Gibran poem printed in Arabic on the restaurant’s green paper placemats.

You have your Lebanon, and I have mine.

“Not all the customers will read it, I know,” Abdul-Hadi remarks.

You have your Lebanon with her problems, and I have my Lebanon with her beauty. You have your Lebanon with all her prejudices and struggles, and I have my Lebanon with all her dreams and securities.

“This street is called Gebran Street. Very few know this. I wanted to pay an ode to him,” he explains.

“He talks of the Lebanon of his dreams and the Lebanon that exists. A hundred years later, we still have the ugly Lebanon. Not much has changed.”

And yet, there is still tradition. There is food, and, of course, heaping bowls of hummus.