Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D (right) used to be the same height as Block C (left) before it collapsed on Oct. 16, killing eight women. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

MANSOURIEH, Lebanon — “This used to be the garden.”

P. J., a resident of Mansourieh in the hills just above Beirut, points down at a patch of dirt and concrete rubble covered by a green tarp. Above it is a tilting, mangled block of 14 apartments with broken furniture visible through the windows. It’s all that’s left of his former home, the Edmond Yazbeck Block D building, which collapsed last month after a rainstorm crumbled a load-bearing column.

Eight people were killed in the disaster, including two of P. J.’s loved ones, as well as a beloved French teacher named Noha and a Sri Lankan domestic worker named Pemalatha. All of the victims were women. P. J. requested his full name not be published to protect his and his family’s privacy.

“We’re still finding things,” says P. J.’s friend, who has accompanied him one morning in November to check on the building and see if they can recover any of their possessions. She unearths a wooden maamoul cookie cutter, once part of P. J.’s kitchen.

Around them, on the walkway leading up to the wreckage, other detritus of former lives: a thick file folder of French homework, a Xeroxed yoga guide, women’s purses arranged tenderly in a row. “We put them there because they belong to people; maybe they’ll come back and take them,” says P. J.’s friend, who also spoke on condition of anonymity.

But, weeks after the collapse, nobody has come to claim the items.

Personal belongings left behind among the debris of Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D in Mansourieh. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Personal belongings left behind among the debris of Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D in Mansourieh. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

There’s also been next to no assistance from public authorities, multiple residents of the apartment complex tell L’Orient Today.

Claudia Ghaneimeh, a resident of the nearby Edmond Yazbeck Block A building, which is part of the same apartment complex, says she and her husband have been sleeping in their van since Oct. 16, afraid their home could also be at risk. They’ve been living on sandwiches and manaeesh, only returning home to grab supplies.

Amid growing tensions along the border between Hezbollah and Israeli forces, connected to Israel’s deadly all-out bombardment of the besieged Gaza Strip, news of the Mansourieh building collapse — which, in other times, likely would have become a national scandal — largely went under the radar.

But the tragedy has further unearthed deep distrust in a state that’s been in economic and political crisis for the past four years.

“I asked [the municipality] for help, for an inspection, if we could return or not,” says Ghaneimeh. But such help has taken a month and a half to even begin arriving, she and other residents say.

Breaking point

It all began in August.

That’s when residents say they first noticed frightening cracks in the parking garage columns.

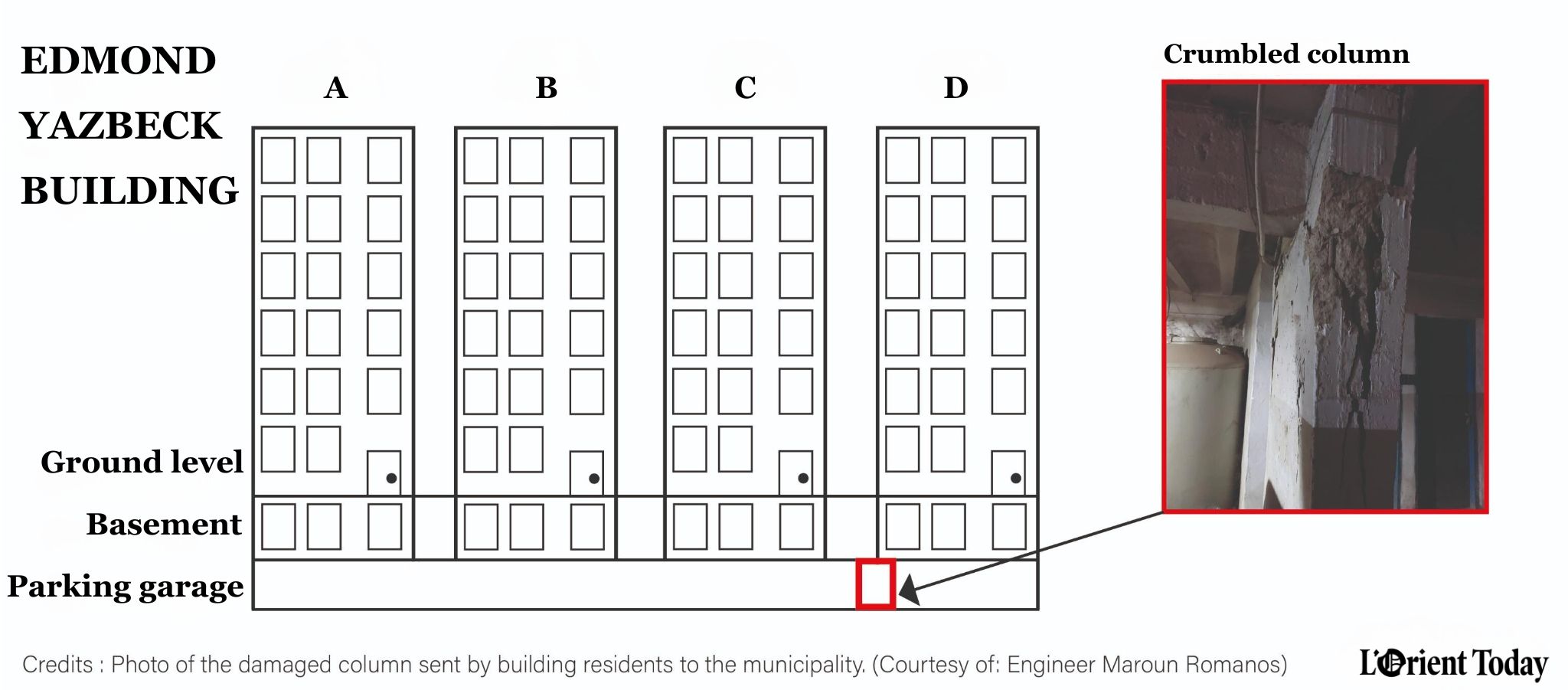

One Block C resident sent photos of the dangerous load-bearing column to Mansourieh municipality member Camille al-Hage, as part of a request for help with the problem. L’Orient Today obtained the photos from Hage, though the resident who sent them declined to comment, saying he was still upset about the collapse of the building next door.

Block D resident Nicole Kondakji — who was living in the building with her parents and brother — confirms to L’Orient Today that she saw the cracked column in August, “right next to my parking spot.”

In the pictures, scales of hard concrete appear to flake away from a load-bearing, rectangular column in the garage, exposing some of the iron rebar within.

Maroun Romanos, a civil engineer and consultant, tells L’Orient Today that he was called upon to inspect the building in August when one of the residents began to complain to the municipality about the column.

“But I was in the south that day, so I asked them to send me the photos and I’d see, maybe I could come back in two days and check,” Romanos explains. What he saw on his phone shortly afterward was the massive, risky fracture — the same parking garage photos that were shared with Hage.

“I told him not to wait two days, that it was too risky.” Block D was in special danger, according to Romanos, because that was the building immediately on top of the crumbling column.

A crevice left behind by the Oct. 16 collapse of Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D in Mansourieh. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A crevice left behind by the Oct. 16 collapse of Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D in Mansourieh. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

According to civil engineers Camille Hashem and Rached Sarkis, residents soon hired a construction company to fix two columns in the parking garage. But, Hashem adds, the company “restored only two columns,” instead of the entire garage. “This is a lack of knowledge of engineering matters.”

“That is not how I would have fixed the columns,” says Sarkis, pointing to a photo he’s saved on his phone of the repair work. In it, workers simply pour new concrete around the existing, water-damaged columns, a fresh face over top of the rot.

The devil in the details

Though it first appeared in August, the fatal crack can be traced to mistakes that began as far back as 1986.

That’s the year the building’s contractors received their license to construct four five-story apartment buildings in Mansourieh with a single parking garage underneath.

Then, in 1987, the owner submitted a license application to build two additional stories, according to Hashem, who is also a representative from the Order of Engineers and Architects (OEA). He visited and inspected the building site after last month’s collapse.

The building’s ground floor — which was previously used only as a lobby — was also converted into apartments. That meant that the parking garage that sits beneath Edward Yazbeck Building Blocks A, B, C and D was now supporting four buildings of seven residential stories each: the basement apartments, the ground floor and the five floors above ground level.

“All of this causes additional weight on the columns,” Hashem tells L’Orient Today, especially those in the garage.

The water tanks for each building’s 14 apartments, which sat on the roofs and weighed down the garage’s thin concrete columns, didn’t help either, explains civil engineer Sarkis, who was delegated by the Mount Lebanon governor to inspect the collapse site and is coordinating with residents of three of the buildings to figure out the next steps. They created a “dynamic effect” as the tanks are emptied, refilled and emptied again over time.

Chairs set up by residents of the Edmond Yazbeck Building complex in Mansourieh near the wreckage of Block D, which collapsed on Oct. 16. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Chairs set up by residents of the Edmond Yazbeck Building complex in Mansourieh near the wreckage of Block D, which collapsed on Oct. 16. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The wreckage of Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D in Mansourieh, which collapsed on Oct. 16. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The wreckage of Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D in Mansourieh, which collapsed on Oct. 16. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

According to Sarkis, the main culprit isn’t all that extra weight only, but rather: water.

That is, water and humidity. “For me, the most important thing is the water that comes from tanks kept in the basement,” he says. Those tanks, which are still present in the Edmond Yazbeck buildings, often leak, leading to flooding that corrodes critical concrete structures like load-bearing columns. These also create a risky level of humidity in the basement, without any aeration – especially in buildings with 10 or more apartments.

“People should know that this is very dangerous.”

“Water is the main culprit against reinforced concrete. Water can affect the life of concrete … and make problems for people and buildings. We have to dry our buildings to eliminate traces of humidity and water infiltration with all its reasons.”

There are other, secondary, water issues, too.

At a mall cafe in Beirut’s Achrafieh, Sarkis pulls out a napkin and a pen, and begins to explain.

The inclined driveway leading into the parking garage of the Yazbeck buildings meant that any time there was heavy rain, it would flow directly into the garage beneath the four buildings. But because there was only one drainage point in the garage — under Block A, according to Sarkis’ impromptu illustration — the bulk of the rainwater would continue on its way to the area under Block D. There, it would pool and sit for days on end, creating dangerous humidity.

‘Like an explosion’

The patchwork repairs back in August weren’t enough.

A new crack began to appear just two months later, on Oct. 16. To make matters worse, a heavy rainstorm the night before flooded the garage for several hours, inundating the already weak concrete supports, Hashem and multiple residents tell L’Orient Today.

Mansourieh resident Nadine Sabbagha, who lives near the Edmond Yazbeck Building complex and knew one of the victims, looks through some of the belongings left behind in the wreckage on Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Mansourieh resident Nadine Sabbagha, who lives near the Edmond Yazbeck Building complex and knew one of the victims, looks through some of the belongings left behind in the wreckage on Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Mansourieh resident Nadine Sabbagha, who lives near the Edmond Yazbeck Building complex and knew one of the victims, walks past the wreckage on Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Mansourieh resident Nadine Sabbagha, who lives near the Edmond Yazbeck Building complex and knew one of the victims, walks past the wreckage on Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

P. J. recalls seeing the fissures in the parking garage that morning before heading out for the day.

Kondakji and a friend, another building resident, were together in the parking garage on the afternoon of Oct. 16 when they, too, saw the crack. She remembers “metal sticks” peeking out from inside of it as the column sagged under the weight of seven apartment stories. They were immediately terrified.

“We agreed to leave right away in our [pajamas],” says Kondakji. “We panicked and shouted out loud in the whole building and [my] mom knocked on all the floors to let them know and to tell them that we should leave right away.”

It was already too late.

“As I was going up the stairs to our floor, we heard a very loud noise like an explosion,” according to Kondakji. Within minutes, the column finally sagged and then crumbled beneath the weight of the seven stories above it, bringing down the building with the residents who were still inside.

Kondakji made it outside just in time. “I was out and a few steps away from the building when I turned around and saw the whole thing collapsing in three to four seconds,” she says. Fortunately, her father and brother were already out of the house at the time, while her mother survived by escaping through a window.

P. J.’s loved ones were not as lucky. He says they had been trying to flee as the building collapsed on top of them.

According to him, rescue workers later found their bodies, one of them still with car keys in her hand.

A mattress crushed in half amid the wreckage of Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D in Mansourieh. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A mattress crushed in half amid the wreckage of Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D in Mansourieh. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A family photo left behind among the debris of Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D in Mansourieh. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A family photo left behind among the debris of Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D in Mansourieh. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Homes turned to ‘dust’

A year ago, in late 2022, the roof of a school in Tripoli’s Jabal Mohsen neighborhood partially collapsed on a 16-year-old student named Maguy Mahmoud, killing her.

The tragedy prompted Parliament to form a subcommittee to track buildings at risk of collapse. Then, in February this year, the government ordered a review of buildings damaged by tremors from the devastating Feb. 6 earthquake that killed more than 50,000 people in Turkey and Syria.

The Lebanese Association of Properties (LPA) claimed less than a week before the Edmond Yazbeck Building tragedy that there were 16,000-18,000 buildings at risk of collapse in Lebanon, further stressed by overdue maintenance works, climate change and improper drainage.

“We have thousands of dangerous buildings in Lebanon,” Hashem says. “They are like bombs waiting for …” He doesn’t finish the sentence.

Hints at what those buildings are indeed waiting for could lie in Edmond Yazbeck Block D.

One Civil Defense volunteer, who was a part of the team sent to Mansourieh to help with the rescue efforts, says it was the worst disaster he’d been called to since the Beirut port blast response on Aug. 4, 2020. When he arrived at Edmond Yazbeck Block D, he says others on the scene pointed him in the direction of where the load-bearing columns that used to hold up the building had been located.

All that was left of them, he tells L’Orient Today, was “dust.” He spoke on condition of anonymity as he was not authorized to give details of the incident to the press. His cell phone images from the scene of the collapse, which he shared with L’Orient Today, show multiple stories squished atop one another, filled with pulverized concrete, “like a mille-feuille,” he says.

In another picture of the collapse aftermath, shared by Hashem, the building appears to have simply crumpled downward, its outer wall scraping the side of Block C as it went.

Block C resident Jean Kayyali and his brother visit his building, which has been evacuated and sealed with tape after the collapsed Block D building hit its outer wall in October. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Block C resident Jean Kayyali and his brother visit his building, which has been evacuated and sealed with tape after the collapsed Block D building hit its outer wall in October. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

“The way the building collapsed proves that the columns were crushed,” says Hashem, and that the repair and construction work on the load-bearing concrete “was very bad.”

It was concrete that held up everything from family photos to cooking utensils to the people who called those items home, now crushed in the rubble.

After a day or two, the Civil Defense volunteer and his colleagues pulled the body of a young, newlywed woman from the wreckage.

“We knew it was her from her wedding ring.”

Fine print and Gordian knots

The Mansourieh Municipality is housed in a somewhat imposing, four-story building in the center of the town’s main commercial street. Early in the afternoon one day in November, when L’Orient Today visits, only two of those stories are open for business. The others — including the mayor’s office — are apparently closed for the day with the lights off.

Was it the municipality’s responsibility to fix the cracked column? And who’s to blame for the collapse in the first place? After all, the owners of the Edmond Yazbeck buildings are the residents themselves; under Lebanon’s 2005 Public Safety Law, it’s up to them to commission and pay for maintenance work to keep their buildings safe, according to Sarkis and other experts.

But that principle is deeply flawed, says Abir Saksouk, an architect and co-founder of the urban planning research platform Public Works Studio, as it doesn’t take into consideration the owners’ financial means.

“When the municipality told the residents that the building was … at risk of collapse, it brought in one of its engineers, who did a report and gave them an estimate of how much the restoration would cost,” Saksouk says, citing Public Works Studio’s field research on the disaster.

A death notice for Nicole Matar, who lived and died in Edmond Yazbeck Block D, posted by residents on the outer wall of the collapsed building to commemorate her. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A death notice for Nicole Matar, who lived and died in Edmond Yazbeck Block D, posted by residents on the outer wall of the collapsed building to commemorate her. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Block D residents ended up choosing a different, more affordable company to do the repair work, she says, as the other one was “too expensive.” (Asked about this point, P. J. said that two engineers — “one our building hired” and the municipality’s engineer — had both examined the building in the months before it collapsed.)

“The law cannot simply [state] that the responsibility is on the owners,” says Saksouk. “There is a gap here.”

Legal discussions aside, Block D has already collapsed, eight lives already lost. Dozens of people now no longer have homes. Is it the state’s responsibility to provide alternative housing and aid?

Yes, say residents.

Lebanon’s Higher Relief Council (HRC), which handles disaster response efforts, did indeed allocate funds to be distributed to the Edmond Yazbeck residents so that they could pay for three months of rent elsewhere, council head Muhammad Kheir told L’Orient Today in mid-November.

Enter the apparent bureaucratic Gordian knot.

A chair left behind among the debris of Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D in Mansourieh. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A chair left behind among the debris of Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D in Mansourieh. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

At his office in downtown Beirut, Kheir said that he tasked Mansourieh’s mayor, William Khoury, with distributing the housing vouchers to residents, as well as checking their IDs to make sure the money was reaching the right people. Kheir maintains that the council has already sent the funds to the municipality.

But, reached by phone shortly afterward, Khoury said he was still waiting to receive the funds, despite having already sent a list of recipients’ names to the HRC.

Residents who spoke with L’Orient Today throughout most of November said they had yet to receive even the rent allowance vouchers. P. J., who described himself and his brother as the ones in their household who manage bills and legal matters, said in the weeks after the collapse he had not heard there was supposed to be an allowance payment or voucher at all. “What voucher?” he asked.

Finally, though, there is perhaps a small glimmer of hope. Speaking to L’Orient Today by phone in late November, shortly before the publication of this article, municipal council member Hage says the voucher funds have arrived. Some Block C residents have already picked up their allotted LL30 million-per-household payment.

As for residents of Block D, their vouchers should be ready “by Monday,” Hage adds. Two Block D residents confirmed to L’Orient Today that they had been informed of the vouchers and were planning to go receive the equivalent in Lebanese Lira of about $300 per household from the municipality.

P. J. and a friend stand by the wreckage of the Edmond Yazbeck Block D building on Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

P. J. and a friend stand by the wreckage of the Edmond Yazbeck Block D building on Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Left in the rain

As winter finally gets underway in earnest, Lebanon can expect dayslong rainstorms as well as low temperatures. Some Edmond Yazbeck residents tell L’Orient Today they are scared about further water damage to the apartment building complex.

Ghaneimeh, who told L’Orient Today earlier this month that she had been sleeping in her van since the collapse, has since been able to find a place to stay outside of Mansourieh, with a relative.

Kondakji, her brother and her parents have managed to rent “a small house” nearby in Mansourieh, where she says they are staying temporarily until they can find someplace better.

As for P. J., he found an apartment to rent, also in Mansourieh. He closed in on the deal in early November, he says during L’Orient Today’s visit to the collapse site, flanked by a muddied, disemboweled laundry machine and some upended dining chairs. It’s a deceptively sunny day; there’s no hint yet of the coming rain.

In a few minutes, he and his friend will light a candle — one of the half dozen or so that residents have placed on a ledge overlooking the wreckage, a makeshift memorial to their neighbors. There are statuettes of saints, a crucifix, an empty Romeo y Julieta cigar box now filled with a prayer booklet.

But first, P. J. lights a cigarette and stares at the rubble where his house used to be.

Does he feel safe in his new apartment building? Or any building, for that matter? He simply shakes his head.

A makeshift memorial set up by residents among the wreckage of Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D in Mansourieh. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A makeshift memorial set up by residents among the wreckage of Edmond Yazbeck Building Block D in Mansourieh. Nov. 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)