A boy walks in the courtyard of a school where displaced families have taken shelter in the city of Sour. Oct. 19. 2023 (Credit: Mahmoud Zayyat/AFP)

It was an ordinary morning for the Nabaa family. Raouia and Hassan sat beneath the awning of their small hillside house in above Kfar Shouba along Lebanon’s southeastern border, enjoying coffee with friends and family. Their six children were still sound asleep.

"Then, everything descended into chaos," Hassan recalled.

On Oct. 8, Hezbollah launched an attack on three Israeli positions in the occupied Shebaa Farms, just a day after Hamas’ violent surprise attack in Israel.

Missiles soared, sending shrapnel flying in all directions. One window after another shattered. Two of the children were wounded.

It’s been a month since that day and the family still hasn't returned home. Raouia sought refuge with the children in the Bekaa, while Hassan, who herds goats and depends on the animals for the family’s livelihood, remained in Hebbariyeh, a village near Kfar Shouba.

"The majority of the country carries on as if nothing has happened,” Raouia said.

For the past month, Lebanon has been embroiled in an unnamed war. In southern Lebanon, the conflict is already in full swing, with daily clashes between Hezbollah and the Israeli state along the Blue Line border.

Currently, both countries appear to be tolerating this precarious situation, but a single misstep could drag Lebanon into a full-fledged war.

Since Oct. 8, 64 Hezbollah fighters and 14 civilians have been killed, while over 29,000 individuals have been forced to flee their homes in border villages.

Hezbollah, and its Palestinian allies in Lebanon, Hamas and the Islamic Jihad Movement, fire from the west and east at Israeli positions.

In retaliation, Israel has been bombarding areas suspected of harboring missile launch pads, close to the towns of Dhaira, Marwahineh and Ayta a-Shaab.

On Oct. 9, the attacks were still sporadic, but for thousands of residents, the warning signs were clear, and the struggle for survival was intense. That day, a shell landed in the kitchen of Hassan Jawad, a resident of Ayta a-Shaab.

During the July 2006 war, this predominantly Shiite village was heavily damaged.

Hassan fled to Sour with his wife and son, where many other displaced individuals sought refuge since Oct. 8. Some found shelter with relatives, while others rented hotel rooms or apartments.

Unluckier families, like Hassan's, ended up living in schools that had been requisitioned in the seaside town.

"In Sour, life goes on as if nothing had happened, while all we have left are ghost villages," said the head of the municipality of Alma a-Shaab, a predominantly Christian border town.

This sentiment was especially high among residents in the first week of hostilities. The Lebanese state has yet to make an official statement on what happened, in fear of clashing with Hezbollah, which holds the country’s fate in its hands.

The Lebanese education minister ordered the closure of some 50 schools in border areas.

Many civilians who sustained injuries from the attacks headed to coastal hospitals.

Yola Souaid, a 43-year-old schoolteacher from Dhaira, was injured in her house by shrapnel from an Israeli attack. When we met with her, she lay on two stacked mattresses on the floor of a public school classroom in Sour.

"I'm stuck in bed because of the wounds, I can't work anymore,” she said. “What am I going to do with my life now?"

Targeting journalists

From the very first days of the conflict, local and foreign journalists rushed to the border to report on the situation.

On Oct. 13, a group of journalists became the aim of Israeli strikes.

While stationed for several hours on the outskirts of Alma a-Shaab, a group of journalists from various foreign media outlets was targeted by Israeli strikes.

Issam Abdallah, a videographer for Reuters, was killed instantly, and six others from the same agency, as well as AFP and al-Jazeera journalists, were wounded. The news sent shockwaves throughout the country.

Abdullah the first civilian casualty and the circumstances of the incident were shocking.

On Oct. 29, 16 days later, Reporters Without Borders asserted that the group of journalists "had indeed been targeted" by Israel.

"Issam was stolen from us,” said Jad Chahrour, spokesman for the SKeyes Center for Media and Cultural Freedom and a close friend of Abdallah. “He was killed doing his job to reveal the truth about the situation at the border.”

During Abdullah’s funeral on Oct. 14 in his hometown Khiam on the border, a retired couple was killed a few kilometers away in Shebaa by Israeli airstrikes.

"The first shell hit the veranda of my brother's house, who rushed to the kitchen with his wife,” said Yahya -Ali Hachem. “Four other shells fell on them.”

Khalil, aged 75, and his wife Zinad Akoum died in the flames of their home.

Panic seems to be reigning over Lebanese homes.

As the war in Gaza intensifies, threats of further escalation on the Lebanese front appear to be growing.

Schools have begun to prepare for the possibility of distance learning, families are stocking up on supplies. embassies are advising their nationals not to travel to the country and urging those already here to leave.

In the south, the Israeli army has been using white phosphorus bombs in its attacks.

On Oct. 16, Brahim's* daughter and son-in-law were found unconscious in their home in Dhaira after having inhaled fumes from the strikes.

Brahim tried to leave the village at night, but as he drove, a cloud of white smoke engulfed the road, causing panic.

An Oct. 31 Amnesty International report confirmed the Israeli army’s use of this incendiary weapon, stating that

the attack on Dhaira must be investigated to determine whether it constitutes a "war crime."

White phosphorus, the use of which is prohibited on civilians, was reported to have been fired in other localities as well, causing fires in the region that destroyed agricultural fields and large swathes of olive groves.

Olive oil is an important staple in Lebanon and a source of pride, especially in the south, where hundreds of families depend on the olive harvest to sustain their livelihoods.

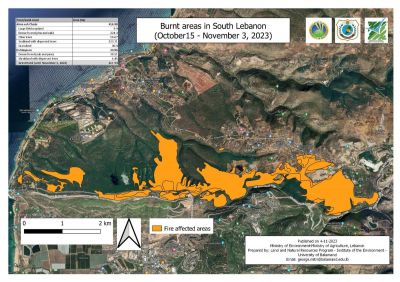

"So far, we've lost 462 hectares of woodland, notably pines and oaks, including around 20 hectares of centuries-old olive groves," said Georges Mitri, Director of the Land and Natural Resources Program at Balamand University.

The rest of the country, however, seems to be more focused on the war on Gaza, particularly since the attack on al-Ahli hospital on Oct. 17, which left hundreds dead and sparked solidarity movements in Lebanon and throughout the Arab world.

In response to the al-Ahli bombing, Hezbollah declared a "day of anger," and thousands of protesters gathered in Nabatieh, Saida and Beirut's southern suburbs.

A demonstration near Lebanon’s American embassy in Awkar degenerated into chaos and vandalism. Thankfully, no injuries were reported. The days that followed raised fears of a military escalation.

As Israeli bombardment intensified over the weekend of Oct. 21, Hezbollah announced that it lost 25 of its fighters since the start of the conflict — almost half died that weekend alone.

It was through social media that Malak Marmar learned of the death of her husband on Oct. 22. He had left for the front four days earlier.

"I had the feeling I wasn't going to see him again,” she said. “I even had a dream about it. I told him and he laughed.”

Ali Mahmoud Marmar, a 29-year-old Hezbollah fighter from Taybeh, died a martyr's death in Ramiyeh on the border.

“It was his ultimate wish,” she said.

‘The war is on’

Tension appeared to ease up after a long weekend of turmoil.

Hospitals across the country, already severely undermined by the economic crisis, are preparing for the possibility of war.

Many inhabitants of southern Lebanon, and even the Bekaa, are considering renting houses in "places considered safer," notably the Chouf, Metn and the rest of Mount Lebanon.

"More than 70 percent of Rmeich’s inhabitants left the village for a long time, but they're starting to come back because life in Beirut is very difficult and very expensive," the village’s mayor Habib Alam on Tuesday.

In the space of a month, this Christian border town of over 7,000 inhabitants has been hit several times, leaving homes and farms damaged.

In Alma a-Shaab, only a hundred or so people remain. In the evenings, young people patrol the area to prevent intruders from entering the village.

Fear that these towns be used as a firing base against Israel appears to be pervasive.

"I don't see any solidarity, not even from the political parties,” said Elias*, a resident of Marjeyoun, who has prepared a year's worth of provisions. “I fear the worst.”

Further west along the border, half of Naqoura’s residents left their homes during the second week of fighting. Businesses are struggling to stay open.

"They're frightened, but they have no other choice - they have to live," said Abbas Awada, president of the Naqoura municipality.

As the bombardment continues, many people are opting to leave their homes. Polls, however, show that over 73 percent of Lebanese people are against going to war.

"The war is all around us... We see and hear it", said Mohammad Abdallah, a resident of Khiam, 24 hours before Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah was due to deliver a speech.

Nasrallah broke the silence he had held since the conflict started with an appearance on Nov.3.

In his speech, Nasrallah denied Hezbollah’s involvement in Hamas' Oct.7 surprise attack. While galvanizing his supporters, Nasrallah made sure to contain their enthusiasm, easing tensions and calls for war.

"Regarding the Lebanese front, we've been in the battle since Oct. 8," Nasrallah said. “What's happening on the border may not seem very significant to some, but it is.”

Nasrallah’s words might have appeased some Lebanese.

On Nov. 5, however, the country was shocked to learn that three young sisters had been killed. Remas, 14, Taleen, 12, and Layan, 10 and their grandmother were killed by an Israeli strike on their car on the road between Aitaroun and Ainata. They had visited the village to pick up school books and were about to return to Beirut, where the family had taken refuge until things calmed down when calamity fell.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.