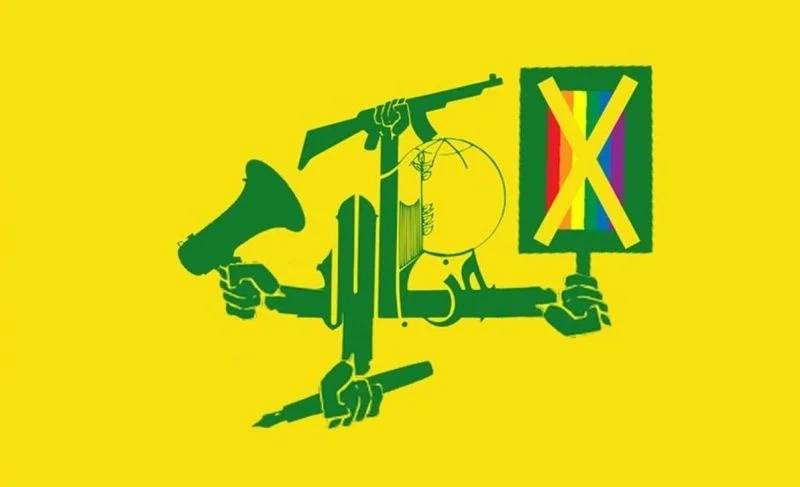

Illustration by Guilhem Dorandeu

On Dec. 25, 1994, while many around the world celebrated Christmas, a significant event unfolded in Iran – the passing of a seemingly ludicrous law but with grave implications.

After lengthy debates, the Majles (Iran’s parliament) enacted a ban on satellite dishes, which had been providing 3 million people with access to international channels.

Users were given a one-month window to dismantle their satellite dishes. Failure to comply would result in intervention by the Basij, Iran’s powerful paramilitary force. Those found guilty would be subjected to trials in revolutionary courts and could face severe penalties, including imprisonment.

The Islamic Republic was still a fledgling state but resolute in its actions. Through this initiative, its aim was to curtail what it perceived as a “Western cultural invasion.” This notion was not novel; as far back as the 1960s, Iranian intellectuals had been cautioning against the perils of adopting foreign lifestyles.

However, the newly established regime transformed this concept into a societal project, elevating this struggle into a political agenda. It was a pursuit that was willing to eradicate a significant portion of the nation’s reality, even though the term itself had yet to be coined – what we now recognize as the “culture war” had come into existence.

Three decades later, the approach has transcended Iran’s borders.

A product of the Khomeinist revolution and one of today’s most influential armed factions in the region, Hezbollah has this summer brought this issue to the forefront.

The party’s focus on countering what it terms the “deviant culture” propagated by the LGBTQ+ community introduces yet another facet to the ongoing “civilizational conflict.”

While still adhering to its customary anti-imperialist rhetoric, Hezbollah is identifying new targets to be attacked. Alongside its established vilification of the “Great Satan,” it is now aiming at the “plotters” at home — an issue that entails “sexual perversion” and “family chaos.”

In June, Hezbollah MPs warned against a situation that “jeopardizes Lebanese society” and “makes it vulnerable to blind imitation of a Western model.”

In mid-August and based on a proposal drafted by a research center affiliated with Hezbollah in Haret Hreik, [a party stronghold in the southern suburbs of Beirut], caretaker Culture Minister Mohammad Mortada signed a draft law providing for tripling the prison sentence for homosexuality.

Things took a quick turn for the worse when Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah declared that Lawat (a derogatory term for homosexuals) must be “punished by death,” “from the first occurrence [of engagement with the same sex].”

Hezbollah is at war.

But the party is not the only one brandishing a homophobic narrative.

Recently, on Aug. 23, a Christian group, referring to themselves as the “Soldiers of God,” attacked members of the LGBTQ+ community gathered at a venue in theMar Mikhael neighborhood of Beirut.

By publicly targeting an already marginalized group, Hezbollah has opened a Pandora’s box.

“The party’s involvement has introduced an additional layer to the topic,” remarked Ziad Majed, a politics researcher and professor at the American University of Paris.

In advocating for both violence and legislative action, Hezbollah has gone beyond the measures taken by many political and religious forces, which often remain content with intermittently echoing the familiar conservative rhetoric.

While some decry an unparalleled attack on “Lebaneseness,” others denounce what they view as “an unprecedented infringement on civil liberties,” according to Hilal Khashan, a political science professor at the American University of Beirut (AUB) and author of “Hezbollah: A Mission to Nowhere.”

Yet, this vilification campaign is pushing boundaries, both in form and substance.

So, why this aggressive stance? If Hezbollah merely aimed to seize political and media attention, as numerous observers suggest, it could have chosen to adhere to its customary methods, as it did when it took a stance against civil unions, for instance, or advocated for early marriages, as it has done in the past.

Is this the inception of a larger movement? Are we witnessing a tactical maneuver or a pivotal strategic shift? In a bid to understand this, a multifaceted analysis is imperative.

‘Westoxification’

Hezbollah is fundamentally a product of its era.

The party’s approach, infused with elements of Khomeinist language, mirrors a global evolution: the allusions found in the “sayyed’s” speeches echo the internal debates unsettling Western democracies.

In the early 20th century, the Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci criticized the detrimental impacts of “cultural hegemony,” where the ruling class endeavors to impose its standards on the broader society.

Several decades later, US sociologist James Davison Hunter coined the concept of a “culture war.”

In this context, the term is used to describe the extreme polarization of public debate on social issues.

On one side, advocates of an “orthodox” model rally for the upholding of “traditional” values across education, religion and sexuality. On the opposing front, “progressive” liberals, as accused by the former group, are labeled as agents of corruption aligned with a reformist agenda.

From Moscow to Beijing, spanning Budapest, Washington, and New Delhi, societies find themselves torn apart by leaders pursuing short-term political advantages.

Hezbollah’s “cultural” crusade is part of this race for ratings but also reflects a regional trend.

For several years, the “new” post-revolutionary Middle East has been keen on preserving a conservative image. With a backdrop of resistance to “westoxification” (or gharbzadegi, as per Jalal el-Ahmad’s 1962 book title in Farsi), some leaders use the identity debate to justify their setbacks and deviations.

Online, there are increasing calls to fight against “cultural invasion” (al-ghazou al-thaqafi).

“This is particularly the case in countries where the economic and social crisis has deepened and where regimes or fundamentalist movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood are exploiting the issue of LGBTQ+ populations in an unprecedented way,” said Joseph Daher, professor at the University of Lausanne.

From Tunis to Cairo, through Beirut, part of the region seems to be swept along by a wind of authoritarianism advancing with a masked face.

Behind a conservative discourse tinged with patriotism, Abdel Fatah al-Sissi’s Egypt intends to block the “culture of normalization” coming from the West.

In Jordan, where secret police harass members of the community, or in Iraq, where Parliament is considering the death penalty for homosexual relations, the prevailing discourse has served as a cover for repressive policies.

By putting its money where its mouth is, Hezbollah has joined this anti-liberal one-upmanship in the name of the common good.

Opportunity

However, the strong push of this campaign, primarily targeted at the Lebanese people, cannot be fully explained solely by global and regional factors. While the party borrows tools and language over which it holds no exclusivity, the ultimate aim is to address internal priorities.

“Because the [subject] is addressed with such ease that other topics lack, this represents a major political opportunity,” explained Ali al-Amin, journalist, intellectual and a Hezbollah opponent. This series of events allowed the party to regain the upper hand in an unfavorable context by bringing the conversation back onto more salutary ground.

Faced with a tense security situation that has rekindled debate over its weapons, stuck in a deadlock over the presidential issue and struggling to address economic concerns, Hezbollah is trying to gain an advantage by opening up yet another front that already aligns with its objectives.

The issue at hand, however, is exceptionally sensitive, as the matter of individual freedoms deeply relates to Lebanese identity, regardless of one’s stance. Though divisive, this subject resonates with all communities.

Hezbollah’s influence extends beyond its core supporters. ‘The party is skilled at targeting public sentiment and understands that those who are against freedom might align with this campaign,” Majed said.

Capitalizing on the widespread challenges, the party “positions itself as the guardian of societal remnants,” according to Daher. Its campaign appeals to a wide audience, seeking stability amid a general breakdown and that is attracted to the reassurance offered by a conservative discourse during times of crisis.

“[The party] is upping the ante, aiming to escalate and make an all-out effort,” Amin said. “It wants to represent a significant portion of the Lebanese population.”

By altering the discussion’s terms, the party is also changing the point of contention: shifting it from political to societal matters. Amid rising unease within the Christian community regarding an armed presence deemed unauthorized, this series of events also brings together the most extreme faction of Christians who disagree with the Vatican’s recent shift toward a more accepting position on homosexuality.

The fact that a significant portion of the ruling class has adopted this approach confirms its effectiveness. Not only have the political heavyweights on the national scene not genuinely opposed the restrictive direction set by Hezbollah, but several major political forces have also followed a similar path. Yet, even eight MPs, mainly from opposition parties, proposed a bill in July to decriminalize homosexuality.

Although not as extreme as Hezbollah, the government, religious authorities, and certain parties have demonstrated the need to address issues related to social matters. In a country where Article 534 of the penal code, which criminalizes any form of sexual activity deemed “unnatural,” still holds sway, state-endorsed homophobia is far from a new occurrence.

In June 2022, the interior minister caused controversy by prohibiting LGBTQ+ gatherings during Pride Month.

A series of statements made by officials throughout the summer reflects an increased political determination. Over the past several months, a significant number of influential figures in the country have been stepping forward to rally to Hezbollah’s apparent call.

In July, several prominent figures from the Druze community, including their spiritual leader Sheikh Akl Sami Abi al-Mona, called for a more intense effort against “the promotion of homosexuality.”

In early August, caretaker Prime Minister Najib Mikati and Maronite Patriarch Bechara al-Rai released a joint statement emphasizing the necessity to counter “ideas that challenge the divine order and the principles embraced by all Lebanese.”

In a speech delivered on Aug. 19 from Hungary, Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) leader Gebran Bassil warned of the danger posed by those “trying to deconstruct the family” and “change human nature,” while reiterating his attachment to freedoms.

On the Sunni scene, Tripoli MP Achraf Rifi, a vocal opponent of Hezbollah, and the Islamic Cultural Center are also aligning with this stance.

By uniting representatives from various communities under its banner, Hezbollah is forming a “broad front,” as Amin said, positioning itself at the forefront.

The short-term political strategy seems to be yielding results.

Not seeing the wood for the trees

Hezbollah’s recent “cultural” outburst has also reignited deep-seated fears. For years, the party appeared content to uphold certain inviolable “red lines” on the Lebanese stage, with the most significant being the protection of its military arsenal.

However, since 2013, its involvement in Syria and Iraq, followed by its backing of Houthi rebels in Yemen two years later, has shifted its priorities.

While Hezbollah has skillfully maintained influence over the country’s institutions through strategic alliances, its main focus remains on preserving the existing national order.

The Oct. 17 uprising and the subsequent economic collapse starting in 2019 have further reinforced this logic of damage control.

The recent summer events are causing concern because they appear to deviate from Hezbollah’s usual areas of focus, such as politics and security.

By capitalizing on its alliances with specific Christian and Sunni groups, Hezbollah aims to emphasize “the values and religious principles it upholds, beyond its political agenda,” said Ziad Majed.

The party’s detractors and defenders of freedoms are sounding the alarm. Is the crusade against homosexuality the tree that hides the forest?

As the Christian community raises the specter of federalism and Hezbollah’s members continue to publicly display their attachment to Taif, could a project for an Islamic republic once again be on the cards?

Nearly 15 years ago, the party publicly renounced the effective implementation of an Islamic state in a multi-faith Lebanon.

“People evolve,” Nasrallah said Nov. 30, 2009, as he announced the amendment of the party’s protocol, which had remained unchanged since 1985.

Despite this “pragmatic” shift, the party never completely severed ties with the Islamism it originated from. Even in 2016, Hezbollah’s second-in-command, Naim Qassem, regarded it as “a project we still believe in, in terms of values and culture.”

If the summer period marks the start of a new phase, it is primarily due to changing circumstances. Regionally, the stabilization of military situations and the trend toward regional normalization have led to a reconsideration of priorities and a strengthening of the Lebanese presence, all while reaffirming loyalty to Iran’s influence.

On the local front, the various collapses have resulted in gaps that Hezbollah is working to fill. Through its social, community and educational network, the political influence it has garnered and the deterrent effect of its military capabilities, the party now possesses the resources to promote a vision closer to its Khomeinist ideals.

The question remains: Is there an intention to do so?

To follow this line of reasoning to its logical conclusion, Hezbollah would need to forsake the local fabric that presently grants it alliances and support extending beyond the Shiite community.

“Although today’s conservatism echoes certain periods in the mid-1980s, the present-day Hezbollah is not the same as it was 40 years ago,” Majed said. “It remains deeply entwined within the confessional structure, which it relies upon.”

The group’s aim to bridge political divides and engage a wide range of Lebanese citizens might indicate an aspiration for broader influence beyond the Shiite community.

Yet, in extending its reach to the country’s Christians and Sunnis, while positioning itself as the leader of a conservative national movement, Hezbollah is also demonstrating its affiliation to, and possibly dependency, on the Lebanese formula.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.