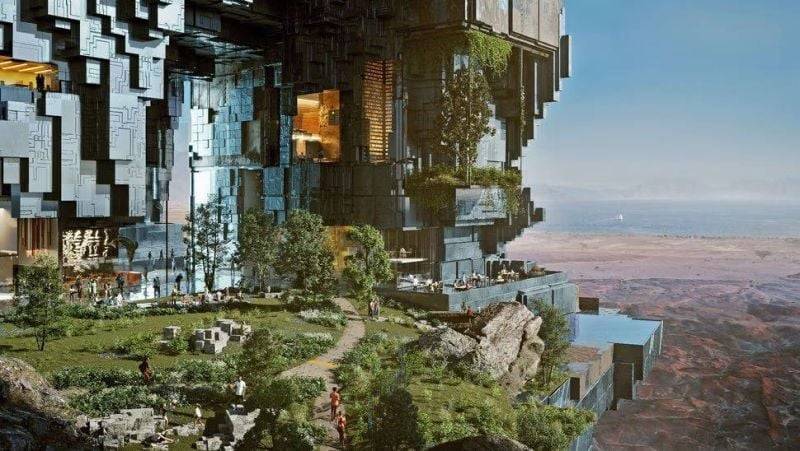

A design plan for the smart city “The Line,” which stretches 170 kilometers long and 500 meters high, within Neom, in the province of Tabouk. (Credit: Neom/AFP)

After being the fastest growing G20 economy in 2022 — with an impressive 8.7 percent growth, boosted by the rise in oil prices — the Saudi economy is now slowing down. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has cut its 2023 GDP growth projection for Saudi Arabia to 1.9 percent, downgrading its June projection to 2.3 percent and its May projection to 3.1 percent.

“The downgrade for Saudi Arabia for 2023 reflects production cuts announced in April and June in line with an agreement through OPEC+,” said the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook report on July 25.

Faced with the expected fall in demand, the kingdom announced on Thursday that it would extend oil output cuts of 1 million barrels a day until September, in order to boost oil prices, which have fallen below $80 in recent months.

According to many analysts, the government based its budget on this price. It hopes to finance its modernization megaprojects, such as its futuristic mega city, Neom ($500 billion) and its huge eco-tourism complex, the Red Sea Project, as part of Vision 2030, which Crown Prince Prince Mohammed Bin Salman (MBS) values.

“If oil [prices are] below $80 dollars for only part of the year [which was the case from April 25 to July 21], that’s not a big problem,” said GlobalSource Partners’ GCC country analyst Justin Alexander. “In the long to medium term, it would raise serious questions if it fell below $70, but we’re not there yet.”

The recent decision by OPEC+ leader Saudi Arabia, along with Russia, to cut oil production is beginning to bear fruit. On Friday, Brent crude closed at $86.29. However, it remains uncertain whether the increased oil prices will hold, as China, which absorbs a quarter of Saudi crude exports, shows signs of a slowdown in economic growth. Beijing is also importing record volumes of Russian (almost 2.6 million bpd last month) and Iranian oil, despite the sanctions.

Time of financial scarcity

But this context does not mean that the Saudi megaprojects and the kingdom’s budget are at risk. While Saudi Arabia currently produces around 9 million barrels of oil a day, its capacity ranges between 12 to 13 million, according to estimates. This leaves enough room for maneuver in the event of a major drop in prices.

“In addition, Aramco will continue to pay taxes and dividends to its investors, which are mainly the Saudi government and other Saudi entities that have shareholdings in the company,” said Jamie Ingram, an analyst at the Middle East Economic Survey. “All this will finance the economy.”

In April, the Public Investment Fund (PIF), Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, doubled its stake in Aramco to 8 percent. The PIF, which is the main source of financing for MBS’s mega-projects, has a staggering $778 billion in capital.

“The Line, NEOM’s flagship city, is being financed directly by the PIF, both through its assets and loans mainly from local banks,” added Alexander.

Meanwhile, Rachel Ziemba, a researcher at the Center for a New American Security, remarked, “If need be, Saudi Arabia would also draw on its past savings, such as the money from the partial sale of Aramco.”

In 2019, Aramco’s initial public offering raised $29.4 billion, a world record for such an operation. Riyadh can also count on its abundant foreign currency reserves, which exceed $400 billion.

“These have fallen considerably and are therefore no longer as robust as in previous years, but they are still more than solid enough to get through one or two lean years,” said Ingram.

The country’s low level of debt — around 23 percent — also allows it to consider borrowing as an option. “Senior officials have said in the past that they were more than willing to increase their share of debt if necessary,” Ingram added.

FDI struggling

Having become more robust in recent years, the Saudi economy is also relying on its non-oil GDP, which stood at 5.34 percent in the last quarter of 2022. This figure is as expected for the kingdom, which views economic diversification as key to its survival.

“Non-oil growth has been hovering around 3, 4, 5 and 6 percent for a number of consecutive quarters, which they haven’t managed to do since at least 2015,” said Ingram. “The non-oil sector is really the barometer of how the economy is doing, and at the moment it’s holding up pretty well.”

The billions invested in sport, tourism and culture are thus justified, almost making NEOM’s $500 billion look like an affordable price tag. “The government can’t really afford to cut spending in these areas; otherwise, it will never be able to break its dependence on oil. This makes it vulnerable to fluctuations in barrel prices, largely beyond its direct control,” added the analyst.

However, Saudi Arabia is struggling to attract foreign direct investment (FDI), which is needed to finance some of its mega-projects. They have fallen by 59 percent in 2022. “Overall FDI is still less than 1 percent of the GDP, which is much lower than Saudi aspirations, and well below neighboring countries such as the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain,” said Alexander.

This situation is exacerbated by the “goose that lays the golden eggs” image generally associated with the oil-rich monarchy. “Everyone sees Saudi Arabia as a source of funding for their own projects rather than a place to invest for themselves,” said Ingram.

As the kingdom tries to attract investment into its mega-projects, the question of their profitability arises. “It can take five or 10 years,” said Alexander. “And there are reasons to be skeptical, because, for example, many of the tourism projects are top of the range. It is not certain that there is sufficient demand for this.”

Moreover, the Saudi interbank offered rate hit a record 6 percent in July, higher than it was during the 2008 financial crisis, which should further discourage international investors. “The slowdown in growth and the rise in interest rates could lead to the scaling back of certain Saudi megaprojects, or delays in their completion, but these projects are politically too important to be abandoned,” said Ziemba. Given the choice, Saudi Arabia will prefer to give them priority and, in order to compensate, [it will] reduce its investments abroad.”

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury.