Dalal Mawad. (Credit: Tarek Moukaddem)

“Covid saved me,” Dalal Mawad said. “I remember tweeting, 'Covid saved us.'”

On Aug. 4, 2020, Mawad, then a senior producer for the Associated Press, was working from home on the outskirts of Beirut, when she heard a striking sound around 6 p.m., “the loudest I had ever heard in my life,” she recalled. “I thought there was an airstrike next to my house.”

“One of the junior producers on my team calls me completely hysterical, crying, telling me that she has no house anymore, her roof is gone. I'm like, Hind, what are you talking about? You live in Gemmayzeh. There's something at the port, maybe. How is that related?”

At that time no one knew the magnitude of the incident. Mawad wanted to know more, but she had to continue working. “I was on a night shift and I was not just dealing with the news in Lebanon. I was dealing with the news in the region. It was horrible because I couldn't focus. I had the TV on and I started seeing the pictures. I was dying because I wanted to go down and they wouldn't let me leave. I had to stay on the desk.”

Mawad didn't sleep that night. At 5 a.m., the following day, she drove to the port. “I had live news to cover for Good Morning Britain from the port at 6 a.m. That's the moment when I realized what had happened. I saw the magnitude of the blast.”

“The explosion was really the apocalypse and the death of the Lebanon that I once knew. For me and for many people, there is always a before and after August 4. There's something that died on this day, forever, that I'm never going to get back. It's maybe a relationship I had with Beirut, my sense of security and safety.”

Mawad moved to Paris soon after.

Oral history

It was during this period that a friend pointed her towards the works of Svetlana Alexievich, a Belarusian journalist acclaimed for her approach to oral history. Mawad was marked by Alexievich's groundbreaking book series “Chernobyl’s Prayer,” which chronicled the personal accounts of survivors from the 1986 Chernobyl disaster. As she read through it, she realized she too could capture the experiences of those impacted by the Beirut blast.

“What [Alexievich] does is she tells the disaster of Chernobyl through very personal little stories of people who survived or lost someone or who were victims of the disaster. It stayed with me for a very long time. You remember the names, you remember the stories.”

Mawad had no formal book proposal, but she wrote a brief pitch which she shared with two agents. Fortunately, both were intrigued and she signed with one of them.

While brainstorming, Mawad decided to dive into all the reporting she did in the aftermath of the blast. “Most of the voices I had were women. It was never on purpose and I say this in the book. Women open up more, maybe because I'm also a woman, maybe because they don't always have the opportunity to speak, so they're more open about their emotions. You know they've been bearing a huge burden throughout history, especially older women who went through the Civil War, the Israeli war, …”

Consequently, Dalal embarked on a two-year mission to give the women affected by the explosion the platform they need and deserve to share their stories. All She Lost delves into the lives of these women, capturing their traumas, their struggles, and their pain.

“My book is really about women, by women, but who are these women? They're not president, they're no minister. They're like regular people, right? And I think that it's somehow my attempt to contribute to our collective memoir, right? Because we don't have a collective memoir. That's what we suffered from after the Civil War. It's this attempt to bring documents and bring together all of these testimonies.”

Processing trauma while writing

Mawad’s extensive research led her to women who had experienced immense trauma and loss. For many, this was the first time they shared their stories in such detail.

“The process of sitting with them, interviewing them, making sure I'm not triggering any traumas, or contributing to them relapsing, although I probably did,” was a challenge, explains Mawad. “It was very uncomfortable being in that position again and again. Maybe it was traumatizing again for me. At the beginning, I would cry, I didn't know how to behave, like we would stop the interview, try to say something, go on, go back. It was heavy, very heavy. And every time I would feel like I'm a shrink, right? Like I'm a psychologist and I'm not. [...] I tried to act based on what I know, based on experience. Because to me being human comes before being a journalist, right?”

Through this emotional struggle, Mawad also found solace in talking to these women, and in writing. “The book helped me process my own trauma, my own feelings, my own emotions, to grapple with what happened. I won't lie to you, I wouldn't say I found peace or anything, quite on the contrary. I think no one will, because it's exactly what my book says, because of that impunity, there's no accountability, there's no justice.”

‘Carrying the burden of the world on [her] shoulders’

Mawad is currently working on a freelance basis as a senior producer with CNN's Paris Bureau. She has also taught video journalism at Sciences Po Paris for two years.

Mawad was raised in an environment where “helping and caring about others was part of our daily life,” she explained. Her father was a doctor and activist, and her mother managed a home for the elderly. “Our house was open to the public 24-7. I used to joke, saying my house was a public garden.”

“I saw injustice against women in my own house, through my grandma. I was very close to my grandma. I have her name. I speak about her in the book and I dedicated it to her. She was a very bitter woman. I saw this woman who lost a lot in her life, her husband, then her brother died in a car accident abroad. Not seeing justice, not liberating herself. She sacrificed her life for her children. Her children ended up being brilliant doctors, but I feel like there was no space for her to be. She always lived for others.”

Mawad’s grandmother was the starting point of her vocation. She fueled her desire to be an agent of change. “I feel like I was quite vocal. And it doesn't mean I wasn't oppressed by society. Quite on the contrary. But I felt like I wanted to use my position to help other women. And that's where I found my voice in journalism as well because I extensively cover domestic violence, migrant women, and workers.”

After postponing her decision to enroll in journalism, which she deemed very biased and dangerous in Lebanon, and after obtaining a first Master’s degree from the London School of Economics (LSE) in International Political Economy (2007), Mawad joined Columbia Journalism School and received a second Master's degree in 2012.

All she lost

The Aug. 4 blast was not the first Mawad had to report on. She covered the explosions in 2013-2014 as well as the Iraq Mosul Operation. She says: “This was the hardest assignment I've ever covered as a journalist.”

“It was affecting me psychologically. It's not a story you report on, go back home and leave on your desk. You live it, you're living it. It's affecting the people you love. It's affecting your family. It's affecting your daily life. You're not a foreign correspondent who can just leave and that's it. You're not here on an assignment. It's my country. It's my home.”

“I love Beirut. I think the explosion made me realize how much I love Beirut. I think I had conflicted feelings towards Beirut, the city itself. It was just love, love, love. I have so many memories in this place. It's where I fell in love. It's where I started going out. It's where I studied. It's where I protested for the first time.”

Despite this love, Mawad felt very little hope at the end. “This is something that I convey in the book because my editor said that the book is very depressing. I'm like, what, you want me to lie? There's no hope. Tell me one thing that makes you think of hope? People who stayed? Good for them. They're fighters, but I'm not sure who's going to get anywhere. I don't judge. I admire the people who stayed. It's hard. People who leave too, it's also hard … That's what people don't understand. You feel guilty for leaving.”

“In the long run, it [the explosion] changed my life. I left and I didn't leave because of the economic crisis. I had a job, I was well paid. The conditions in Lebanon were so bad to raise a child. I felt like I could not protect my child. I don't want her to live through the same thing again. I lived through all of these things.I don’t want to give her generational trauma.”

“The global message to remember is that history repeats itself when there's impunity. This is why you feel like these women are going through the same again and again. Remembering how a woman protected her child during the Civil War under the bomb only to see him get killed 30 years later in a huge explosion. I find this mind-blowing. It's almost as if these women have no escape unless they leave.”

Mawad’s book will be launched Aug. 3, worldwide, with Bloomsbury Press. Antoine Lebanon started pre-sales on Aug. 1. Mawad will organize a book-signing event at Aaliya’s Books in Gemmayzeh in Oct. 2023.

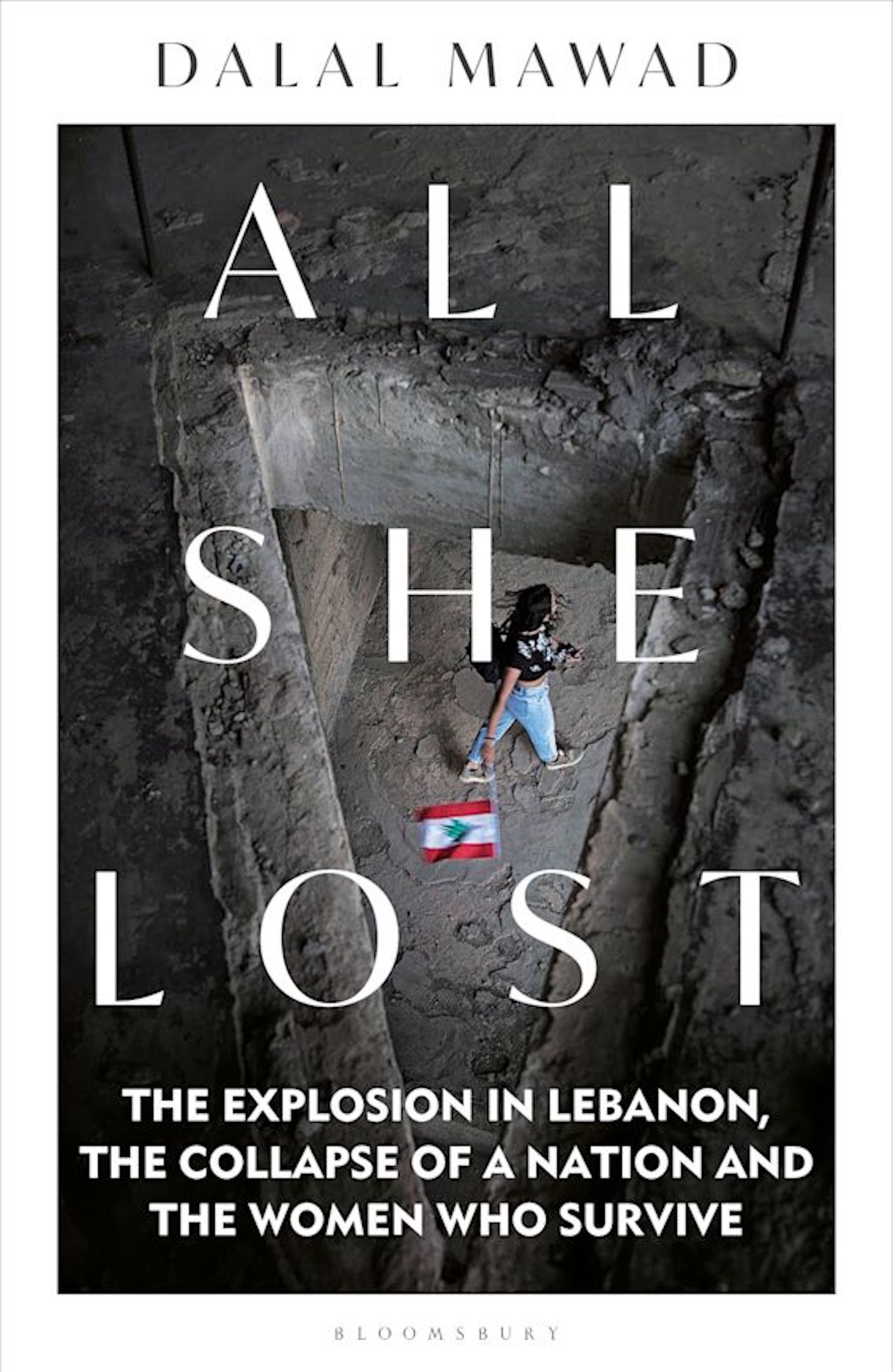

(Credit: Courtesy Bloomsbury Press)

(Credit: Courtesy Bloomsbury Press)