Sudanese Club Vice President Alaa al-Din Taher and several club members relax on the club’s balcony after a funeral for someone who died of an illness back home in Sudan. June 25, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

BEIRUT — Idris Ali boarded a plane in Khartoum carrying a small suitcase, a piece of paper with his uncle’s handwritten Beirut address, and “the clothes on my back.” Many hours and a layover in Jeddah later, he stepped onto Lebanese soil for the first time. It was 1967, and he was 13 years old.

“I wasn’t scared,” he insists. The oldest of four children, he had been sent by his family from Dongola, a city on the Nile River in northern Sudan, to go earn money he could send home. It wasn’t unusual at the time: in the 1950s and 1960s, Sudanese boys and men began traveling to Lebanon in droves to work in the homes of wealthy Lebanese politicians and businesspeople, including former Prime Minister Rachid Karami and Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) founder Kamal Joumblatt. Many came from similar jobs as butlers, cooks and housekeepers in moneyed districts of Cairo and Alexandria, and followed their employers to Lebanon. Work visas weren’t as strict at the time — after landing, Ali simply walked, alone, through Lebanese customs and flagged down a taxi to central Beirut. The driver had trouble understanding his Sudanese-accented Arabic.

“I was just going to stay for five years to work, and then go back home to Sudan,” Ali says.

A picture of Idris Ali as a 13-year-old boy, taken shortly after his arrival in Beirut in 1967. He still keeps the photo on display in his apartment in Hamra. June 11, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A picture of Idris Ali as a 13-year-old boy, taken shortly after his arrival in Beirut in 1967. He still keeps the photo on display in his apartment in Hamra. June 11, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Idris Ali, who first came to work in Lebanon as a 13-year-old boy in 1967, poses across from the home in Hamra where he first stayed after his arrival. June 11, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Idris Ali, who first came to work in Lebanon as a 13-year-old boy in 1967, poses across from the home in Hamra where he first stayed after his arrival. June 11, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

But 56 years later, he has a tidy one-bedroom apartment in Beirut’s Hamra neighborhood and works as a chauffeur and housekeeper for the same prominent Lebanese business family that hired him as a boy in the 1960s.

He’s been back and forth between Beirut and Sudan to get married, visit his kids and, once, in the 1980s, to ferry aid supplies in his own suitcases for Sudanese flood victims. But after decades witnessing war, economic crisis and extravagant wealth, Ali says Lebanon has become a sort of home.

That home was made sweeter by the Sudanese Club, a modest, ground-floor social hall tucked away in a residential sidestreet of Hamra. Overgrown tree branches obscure the electric-lit sign out front, next to a narrow balcony with plastic chairs and coffee cups. It’s still active today, a relatively unknown corner of Beiruti history that has, somehow, survived multiple wars, a pandemic and a countrywide economic crisis that thrust thousands into poverty. And since the breakout of Sudan's deadly war last April left Lebanon’s Sudanese workers scrambling to keep in touch with loved ones back home, the club gained new resonance as a place to catch up on news of the fighting.

The Sudanese Club is the official gathering spot for the more than 11,500 Sudanese citizens who live across Lebanon, according to UN data collected last summer. Most live in Beirut and the city’s more affordable industrial outskirts, though some are also scattered across Jounieh, Aley and anywhere else they can find work. The vast majority are men, here via Lebanon’s kafala (“sponsor”) work visa system that leaves foreign workers at risk of abuse, their passports and other documents in the hands of their employers.

The main salon of the Sudanese Club. May 7, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The main salon of the Sudanese Club. May 7, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Members of the Sudanese Club in Hamra relax on the club’s balcony one Sunday afternoon after the funeral for someone who died of an illness back home in Sudan. June 25, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Members of the Sudanese Club in Hamra relax on the club’s balcony one Sunday afternoon after the funeral for someone who died of an illness back home in Sudan. June 25, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The club “isn’t overtly political, but it has a political function, especially in a place that’s so anti-Black, legally and economically and socially as racist as Lebanon,” according to anthropologist Anna Reumert, who has published numerous studies on Sudanese migrant workers.

“It’s a safe space.”

Today’s members play cards and dominoes in the backroom or watch TV in the main salon, beneath murals of the Sudanese and Lebanese flags. On weddings and holidays, they get together for music interwoven with Sudanese incense from painted clay pots.

The men and women at the Sudanese Club count chauffeurs, electricians and manual laborers among their ranks. Back in 1967, though, when Idris Ali arrived in Beirut, most club members had come to Lebanon for one reason: to earn money cooking food in the homes of Beirut’s glittered elite.

From Malcolm X to Muhammad Ali

In the club’s formal salon are stacks of Qurans, a few sofas and a framed black-and-white photograph of former Lebanese President Charles Helou on the wall. A glass display case holds woven Sudanese baskets and incense pots. There’s also a photo of a dozen or so Sudanese men dressed in sharp three-piece suits, posing solemnly for some unseen camera. They are all cooks.

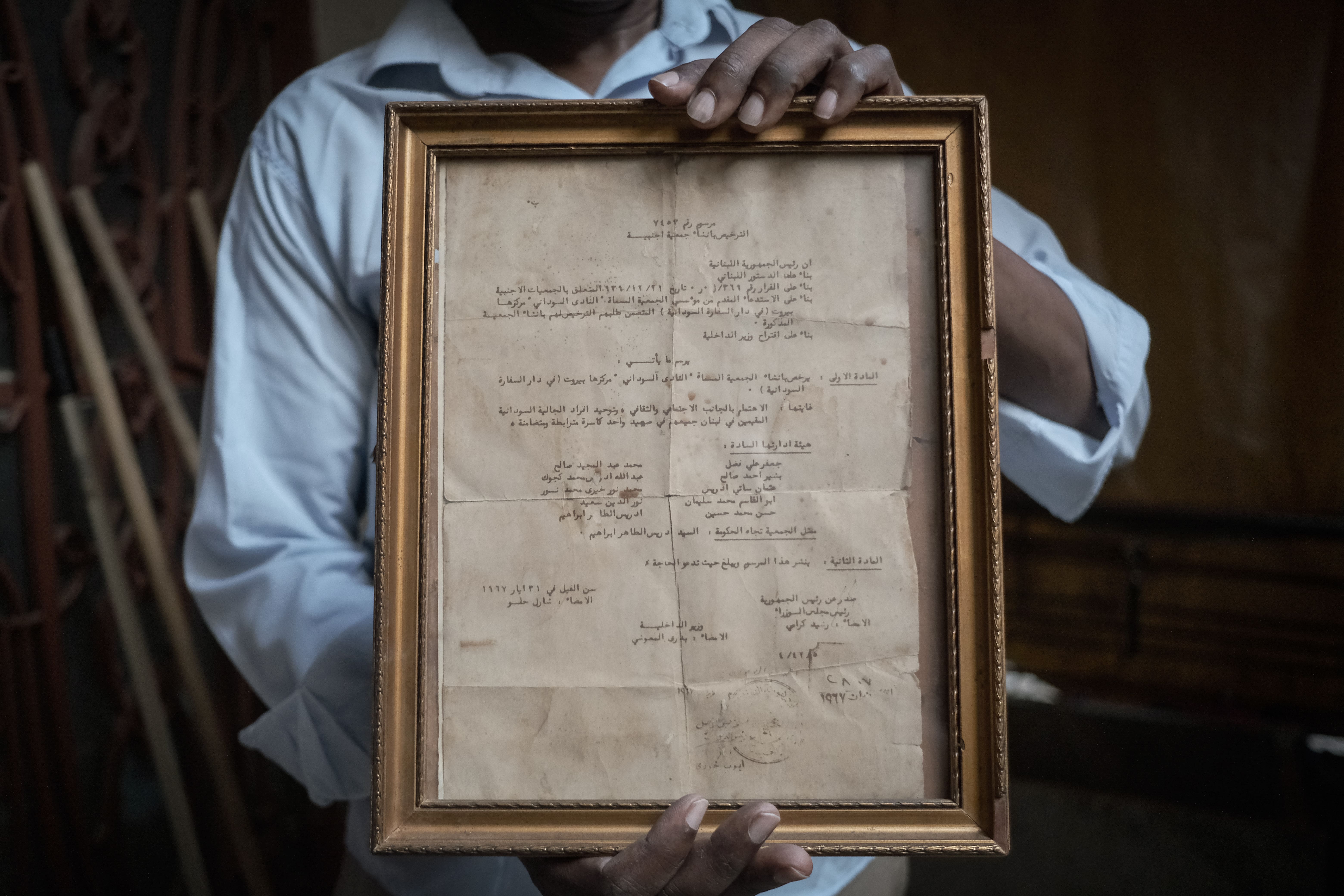

“That’s from 1966,” explains Abdalla Malik Abdelsid, a former club president. A year later, the men in the photo would get a signed decree from Charles Helou to found the Sudanese Club – the first of its kind in Lebanon, according to Reumert. The signed decree is still framed on the wall of the club’s formal salon.

“They decided to find a place they could be that was their own,” says Reumert. Before that, the popular Sudanese hangout was a Palestinian-owned cafe in downtown Beirut. But even there, the men would get anti-Black slurs from passersby. When the club in Hamra became official in 1967, “it was a place where they could organize” for social events and aid drives, she explains.

The 1960s were also a time “when many anti-colonialism movements were mushrooming in Beirut,” according to Reumert. Just a few years earlier, in 1964, renowned Black civil rights activist Malcolm X spoke about the plight facing Black Americans in a lecture near the American University of Beirut, at the invitation of Sudanese students – audience members were polarized around his speech, he would later write in his diary. It was one of two visits he paid to Lebanon in the months before his assassination in 1965.

The founding members of the Sudanese Club, posing for a picture in 1966, a year before the club’s founding. All of the men in the photo worked in Lebanon as cooks, club members explain. Only one of them, the man on the bottom left, is still alive. May 7, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The founding members of the Sudanese Club, posing for a picture in 1966, a year before the club’s founding. All of the men in the photo worked in Lebanon as cooks, club members explain. Only one of them, the man on the bottom left, is still alive. May 7, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Former club president Abdalla Malik Abdelsid holds up the 1967 decree, signed by Charles Helou, officially establishing the Sudanese Club. Members still keep the decree on display in the club’s formal salon. June 25, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Former club president Abdalla Malik Abdelsid holds up the 1967 decree, signed by Charles Helou, officially establishing the Sudanese Club. Members still keep the decree on display in the club’s formal salon. June 25, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

“I don’t remember much from that time,” says Ali, the housekeeper who first came to Lebanon as a 13-year-old.

Instead, he would grow up immersed in the kitchens and dining rooms of Hamra’s Sudanese domestic workers.

“There were Sudanese working in that building, and in that one, too – and in that one,” he points as he walks through the neighborhood one afternoon in June. “I knew them personally.” He passes a vacant lot just around the corner from his apartment, now overgrown with weeds. “I knew the families in the building that used to be there.”

After about three minutes, Ali reaches a several-story residential building on a Hamra street corner lined with trendy bars. He points up: the second-floor apartment, above what is now a popular pub, is the address that was scrawled on the slip of paper he took with him from Khartoum as a little boy in 1967.

There, Ali’s uncle Muhammad was already working as a home cook for a Lebanese family, he says. The family let 13-year-old Ali stay with them after he arrived, alone, in the taxi from the airport.

Fewer than three weeks later, Muhammad found Ali a job as a home waiter and personal chef-in-training for a wealthy family in another part of Hamra. He packed up his things and moved into the room that the family had set aside for him in their luxury apartment.

Ali’s memories of those early ensuing years are hazy, he says. What does stand out to him is a 1974 visit to the Sudanese Club by renowned American boxer Muhammad Ali. “I was so excited to see him!” he remembers. “We all stood in a line and shook his hand.”

His five planned years in Lebanon stretched on, and soon, he was a young man, 21 years old and still working at the job his uncle had found him.

In 1975, his life changed again.

Men play dominoes at the Sudanese Club. May 7, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Men play dominoes at the Sudanese Club. May 7, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

‘A home for all the Sudanese’ amid civil war

In April 1975, Lebanon’s already nascent sectarian tensions ignited into a full-on civil war. Over the next 15 years, tens of thousands of people would be killed and entire neighborhoods of the capital turned to rubble blanketed in weeds.

All the while, the Sudanese Club remained open. Even as their employers left for their home villages or abroad, Ali and other Sudanese workers stayed behind in Beirut.

But things would get worse. In June 1982, days after invading South Lebanon, Israeli forces surrounded Beirut and began to pummel the city by land, air and sea. Thousands of people were killed in the onslaught.

“I wasn’t especially scared,” says Rashdi al-Haj Hafez, who worked as a cook in Beirut in the early 1980s. His father served as president of the Sudanese Club and personal chef to former Prime Minister Rachid Karami for several decades. Some days, Rashdi remembers, Israeli tanks would linger on the street below his Jnah apartment as he and his father played cards on the balcony. Other times, bombs would fall nearby. Still, he says, as Sudanese citizens, “we weren’t really part of the war.”

“In the constitution of the club, it is mentioned that they should not be political in Lebanon,” explains anthropologist Reumert. “They were founded … on the condition that they remain neutral on Lebanese ground. They are not allowed to join Lebanese unions, Lebanese parties.”

Though some Sudanese workers are said to have aided the Palestine Liberation Front, a group affiliated with the Palestine Liberation Organization, according to Reumert, most of them rode out the war largely neutral, looking after the homes of their wealthy employers.

The family Ali worked for in Beirut had fled the city, leaving him alone in their luxury apartment to fend off dust and debris. There was little for him to do. Once, a nearby explosion blew out the windows, giving him no choice but to sweep the broken glass himself.

In the quieter moments, he’d brave the streets to the club and catch the latest news with his friends.

One day, during the height of the 1982 siege, a fellow Sudanese Beiruti and amateur photographer came to Ali with an idea to cut through the anxiety: Why not dress up in his finest suit and pose for a portrait in his employer’s fancy salon?

The photograph still hangs, framed, on the wall in Ali’s Hamra apartment: Him, nearing 30, with a trimmed mustache and an (almost) full head of fluffy hair, sitting regally on an immaculate white loveseat.

Outside, the fighting still raged.

Idris Ali posing for a picture in his best suit at his employer’s house during the 1982 siege of Beirut. A friend took the photo of him to help lessen the anxiety of living through the siege. June 11, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Idris Ali posing for a picture in his best suit at his employer’s house during the 1982 siege of Beirut. A friend took the photo of him to help lessen the anxiety of living through the siege. June 11, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A Sudanese newspaper shows Idris Ali sitting next to former Lebanese Prime Minister Takieddin al-Solh in the Sudanese Club in an article about Ali’s efforts to send aid to flood victims. June 11, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A Sudanese newspaper shows Idris Ali sitting next to former Lebanese Prime Minister Takieddin al-Solh in the Sudanese Club in an article about Ali’s efforts to send aid to flood victims. June 11, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

When the clashes came to Hamra, Ali and the other club members let their Lebanese neighbors seek shelter in the club, which was relatively safe on the ground floor. Sometimes the men would huddle together in the apartment Ali shared with his friends in Hamra, listening to the sound of artillery and gunfire outside.

He remembers one somewhat quiet day at the club, when he and a couple of other men were sitting in the salon. Suddenly a group of Israeli soldiers walked in from the street carrying big guns.

“Of course, we were nervous!” Ali says. One of the soldiers began to speak in Arabic, and introduced himself as a Jew whose family had emigrated to Israel from Sudan. To this day, Ali figures the young man had heard about the Sudanese Club and wanted to stop by.

Either way, once the soldiers left, they never returned.

‘Nobody wears suits anymore’

According to Reumert, the kind of jobs Sudanese workers took on began to change in the 80s and 90s after the civil war ended. “Specifically Sudanese labor was very male-gendered and niche before the civil war,” she explains. “It was butlers, cooks, that kind of thing.”

But when the dust cleared, prominent Lebanese figures like Rafik Hariri, who would go on to become prime minister, began to set their sights on vast reconstruction projects.

“There’s been much more labor demand in the hospitality sector and in the service sector [since then] – forms of previously domestic labor that have been outsourced to restaurants,” Reumert says. Incoming Sudanese workers began to work as restaurant busboys, scrapyard sorters and manual laborers, while domestic work became relegated to women arriving from Ethiopia, Kenya and elsewhere via Lebanese kafala job agencies.

Sudanese men watch a football match in Ouzai after attending the funeral of a fellow Sudanese worker who was killed in May while sorting debris at a nearby scrapyard. May 21, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Sudanese men watch a football match in Ouzai after attending the funeral of a fellow Sudanese worker who was killed in May while sorting debris at a nearby scrapyard. May 21, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A funeral in Ouzai for a fellow Sudanese worker who was killed in May while sorting debris at a nearby scrapyard. May 21, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A funeral in Ouzai for a fellow Sudanese worker who was killed in May while sorting debris at a nearby scrapyard. May 21, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The new jobs were often dangerous – and still are. One accident this past May saw a young Sudanese worker killed by unexploded ordnance while sorting electrical appliances in a private scrapyard in Ouzai, colleagues told L’Orient Today at his funeral.

All the while, Lebanon’s older Sudanese workers, like Ali, are largely still working in the homes of wealthy families or for international companies. The generational divide has begun to calcify inside the club.

“Nobody wears suits anymore to the club,” laments Rashdi. One evening in early June, he joins Ali at a cafe near his home in Jnah, a tiny place off the highway that he says Sudanese guys like to frequent when they don’t want the noise of the more popular cafe down the road. Both men are wearing crisp, pressed pants and collared shirts for the occasion.

“This is like the Pandora’s Box of Sudanese political history,” says Reumert. “There is an intergenerational tension that is very much alive … it’s also a class division, a geographical division.”

“In Lebanon, the older generations [of workers] came from the north [of Sudan],” she adds. “Then since the ‘90s, people have been coming to Lebanon more from western Sudan, Darfur and Kordofan,” because of wars in those regions.

“That is a big demographic change, it’s a class change that maps onto ethnicized differences.”

And though the Sudanese Club is still the official center of Sudanese social life in Beirut, the lives of many younger workers have ballooned out from Hamra to cafes, informal restaurants or football fields, like the one in Ouzai where the men now have rival football teams.

Most simply drift between all those spaces, workers say.

War from afar

Today, Idris Ali rarely goes to the Sudanese Club, despite having served as club president in the 1990s. Only one of the founders from that black-and-white framed photo in the Sudanese Club salon is still alive, members tell L’Orient Today. He’s suffering from dementia and resides in the nearby Clemenceau neighborhood amid the arch-windowed old houses.

“Everyone I used to know has died or left,” Ali says. “When I walk in there now, all I see are strangers.”

Idris Ali and Rashdi al-Haj Hafez sit together after meeting at a cafe in Beirut. Neither of the men still regularly attends the Sudanese Club, they say. Rashdi is the son of another Sudanese worker who came to Beirut to work as Rachid Karami’s personal chef and who later acted as a mentor to Idris when he arrived as a young boy in 1967. June 16, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Idris Ali and Rashdi al-Haj Hafez sit together after meeting at a cafe in Beirut. Neither of the men still regularly attends the Sudanese Club, they say. Rashdi is the son of another Sudanese worker who came to Beirut to work as Rachid Karami’s personal chef and who later acted as a mentor to Idris when he arrived as a young boy in 1967. June 16, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Idris Ali watches a news report about the fighting in Khartoum, at his apartment in Hamra. June 11, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Idris Ali watches a news report about the fighting in Khartoum, at his apartment in Hamra. June 11, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Mostly he watches endless live TV updates on the war in Sudan. Grainy cell phone footage of an explosion on an urban street, huge clouds of black smoke hanging over a skyline, soldiers filing past an unseen camera in military vehicles – Ali points at the TV screen and says he recognizes every single one of the locations on the Al Jazeera live news broadcast.

More than 1,000 people have been killed in the war and three million displaced in just four months, according to the UN’s International Organization for Migration.

Ali’s wife, whom he married in 1983, and his children had still been living in Sudan. In April they were forced to flee their home in Omdurman, a city just north of Khartoum. They are now staying in Egypt, where Ali sends them money to pay rent.

He says he still has no idea what happened to the house in Omdurman, which he bought for his wife and children with remittances from decades of wages in Lebanon.

“I spent 55 years building that house and now I don’t know if it’s still standing.”

Ali’s absence from the Sudanese Club is leaving him to watch today’s war largely alone, from afar.

On his off days, Sundays, Ali instead spends much of his time in the apartment, often caring for the immaculate closet of European suits his employers have gifted him through the years, though the suit from the 1982 picture is long gone, he says; too much time has passed.

Some days he visits old friends who, after all these years, remain in Beirut. Other times, in quiet moments, he simply walks along the sea.

Men pray at a funeral in Ouzai for a fellow Sudanese worker who was killed in May while sorting debris at a nearby scrapyard. The men at the funeral also attend the Sudanese Club. May 21, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Men pray at a funeral in Ouzai for a fellow Sudanese worker who was killed in May while sorting debris at a nearby scrapyard. The men at the funeral also attend the Sudanese Club. May 21, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Those at the Sudanese Club say the recent Eid al-Adha holiday was muted this year, as the men didn’t feel it was appropriate to celebrate amid all the displacement and death back in Sudan.

Instead, there are hours and hours of azaa funeral gatherings, both for those who died here in Lebanon and those killed in the war at home.

On one recent Sunday, several dozen club members gather to mourn one man’s relative, who died of illness back home in Sudan. The war meant the man couldn’t get to a working hospital. By afternoon, some people are still filing in, their mopeds parked across the street, while others have been chatting and sipping coffee for hours. A few women walk in and out of the formal salon, children weaving between the adults.

Soon, it’s time to clean up after the day’s funeral, to prepare the club for an evening of the usual cards, dominoes and chitchat.

Buckets, mops, and suddenly – darkness. The generator sputters out. It’ll be some time before the electricity comes back, one club administrator explains.

Still, the club members keep going, 10 minutes, and then 20, quietly scrubbing at the floors while the sun dips away.

Sudanese Club members relax on one of the club’s balconies. June 25, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Sudanese Club members relax on one of the club’s balconies. June 25, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)