A Lebanese flag lowered to half-mast at Baabda’s presidential palace, Nov. 1 2022, the day after the departure of former president Michel Aoun. (Credit: Dalati Nohra/archive)

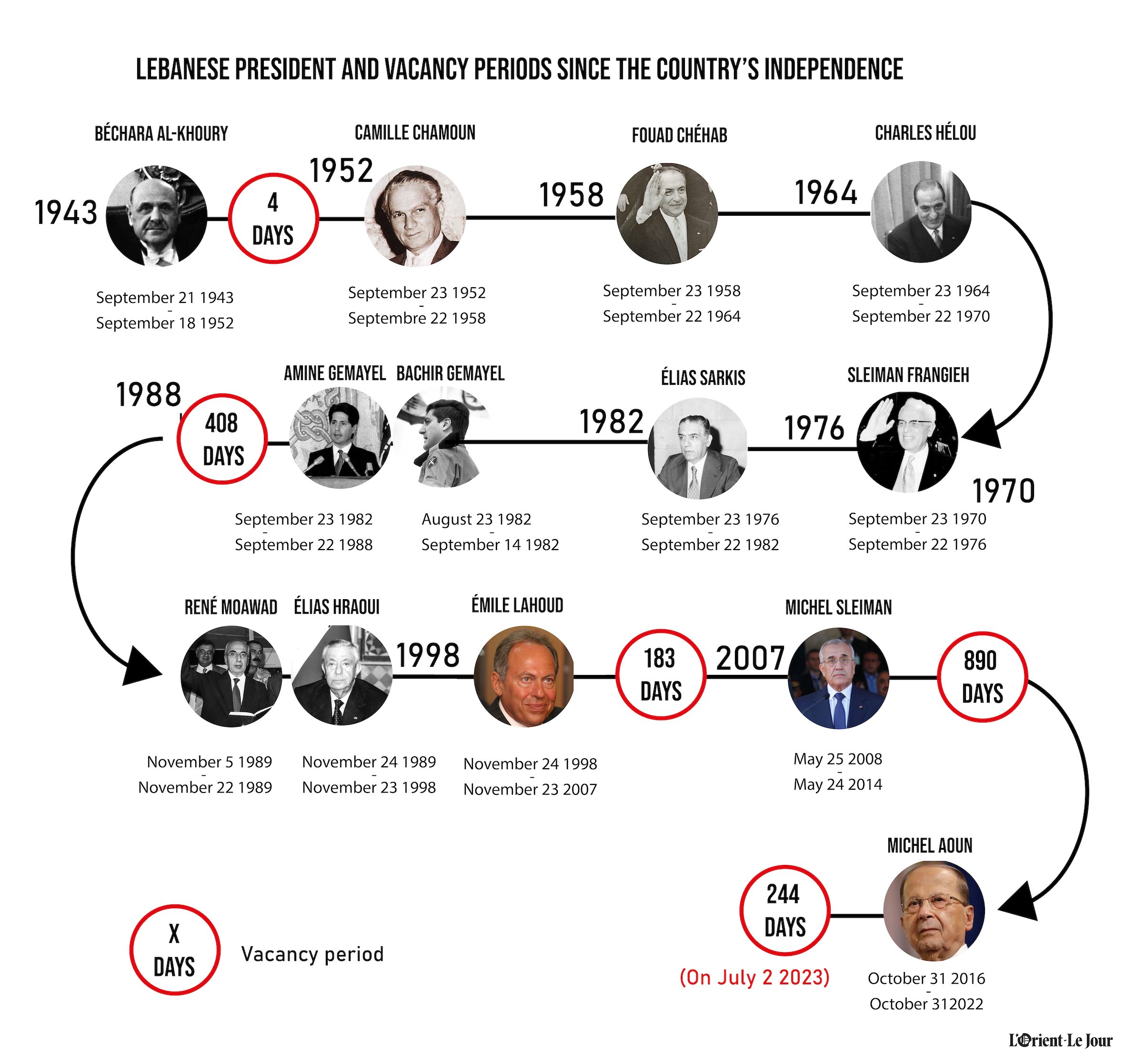

Has Lebanon become the land of the impossible presidential election? Since the end of Michel Aoun’s six-year term on Oct. 31, the political deadlock has persisted: eight months of vacancy, 12 electoral sessions leading nowhere and various parties are still sticking to their positions. This situation is not new. Since independence, Lebanon has been governed by 13 heads of state of every stripe, four of whom have waited more or less as long to be elected. Why has this happened? Each episode has its own causes. L’Orient-Le Jour takes stock.

(Infographic credit: Guilhem Dorandeu)

(Infographic credit: Guilhem Dorandeu)

Since 1943, there have been a total of five periods when the country’s executive has been vacant, including the current one: two before the Taif Agreement — which was accompanied by Syrian tutelage over Lebanon until Damascus’ forces withdrew in 2005 — three since Taif was signed in 1989.

Lebanon experienced the longest vacancy in its history after the 2008 Doha agreement. It was for the good reason that the principle of consensus established after this agreement — which spared Lebanon another civil war — was new for the Lebanese actors, who were used to simply endorsing the model imposed by Damascus.

From Sept. 19 1952 to Sept. 22 1952: 4 days

On Sept. 18 1952, President Bechara al-Khoury, whose six-year term had been extended in 1949, resigned following popular anger against the rule. Lebanese army commander-in-chief Fouad Chehab was appointed to lead a transitional government tasked with organizing presidential elections within three days. Progressive Socialist Party head Kamal Joumblatt supported the candidacy of MP and former minister Camille Chamoun against former Foreign Minister Hamid Frangieh. Frangieh eventually withdrew from the presidential race. Camille Chamoun was elected on Sept. 23. 1952.

From Sept. 23, 1988 to Nov. 4, 1989: 408 days

Amin Gemayel’s term of office came to an end on Sept. 22, 1988, in the midst of the Civil War. Damascus agreed to the possibility of renewing his term, but the Christians (in particular Lebanese Forces Leader Samir Geagea, and army commander-in-chief Michel Aoun) were opposed. Political partners Syria and the United States tried to impose Maronite Akkar MP Mikhael al-Daher, an independent with good relations with the Syrian regime, as president. US envoy Richard Murphy warned that it would be “either Mikhael Daher [as president] or chaos.”

His candidacy was rejected by the Christian camp, however. Before handing over power, Gemayel appointed General Michel Aoun to head a transitional military government tasked with organizing the presidential election; the post of prime minister is traditionally reserved for a Sunni but Aoun was Maronite. Gemayel had based his decision on the 1952 precedent. Prime Minister Selim Hoss, protected by Damascus, refused to recognize the legitimacy of the Aoun cabinet: two governments claimed executive power.

On Oct. 22 1989, MPs signed the Taif Agreement to put an end to the Civil War. This document of national accord, which regularized the Syrian army presence on Lebanese territory and reduced the prerogatives of the President, was rejected by Aoun and his supporters. Aoun dissolved Parliament, but MPs did not recognize his action, believing that he did not have the prerogatives of the president. Parliament therefore met on Nov. 5, 1989, re-elected Speaker Hussein Husseini, and ratified the Taif Agreement. René Moawad was elected President the same day, against a backdrop of agreement between Washington, Riyadh and Damascus.

From Nov. 24, 2007 to May, 24, 2008: 183 days

Emile Lahoud left the presidential palace on Nov. 23 2007, after nine years in power. A deadlock concerning his successor ensued due to a rift caused by the polarization of the sovereigntist March 14 camp and the March 8 camp (united around Hezbollah) in the wake of the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri and the Syrian withdrawal in 2005. The interests of several local, regional and international powers, notably Egypt and the United States, converged on the election of Army chief Michel Sleiman, seen as a consensus figure. Sleiman, who still needed the green light from the March 8 camp, faced his toughest test yet: Hezbollah allies’ armed interventions in West Beirut and Druze-Christian Mountain Lebanon on May 7, 2008. The army remained neutral throughout, allowing Hezbollah to take control over many parts of the capital. At the same time, the troops defined “red lines” that were not to be crossed. For example, the military deployed in Sunni Tariq al-Jadideh, a Hariri stronghold, to warn Hezbollah gunmen that they were forbidden from entering the neighborhood. In the end, this enabled Sleiman to win the confidence of all actors. In the Qatari capital, Arab and international efforts to reach an agreement led to the election of Michel Sleiman on May 25, 2008.

From May 25, 2014 to Oct. 30, 2016: 890 days

This is the longest vacancy that Lebanon has ever experienced. Following the end of Sleiman’s tenure, MPs of the March 8 camp boycotted parliamentary sessions devoted to electing a president, due to a lack of consensus on a candidate. The founder of the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), Michel Aoun, supported by Hezbollah and its backers in Iran, was elected more than two years later. His accession to the presidency was the result of a compromise between the FPM on the one hand and, on the other, Samir Geagea’s Lebanese Forces, Aoun’s opponents on the Christian scene and the Future Movement’s Saad Hariri, who was appointed prime minister.

From Nov. 1, 2022 to date: 244 days (until July 2, 2023)

After 11 electoral sessions without a breakthrough, during which the March 8 camp cast blank ballots and prevented a quorum to impede the election of MP Michel Moawad ,the opposition candidate (LF, Kataeb, PSP, independent and Change MPs), Hezbollah andAmal officially announced their support for the Marada leader Sleiman Frangieh. To strengthen its position, the opposition, joined by the FPM, fell back on former Finance Minister Jihad Azour. Azour did not receive enough votes to be elected in the 12th electoral session on June 14, however, though he received more votes than Frangieh. To break the deadlock, French President Emmanuel Macron dispatched his special envoy Jean-Yves Le Drian to Beirut to hold talks with all actors.

In Lebanon, the president is therefore often chosen long before Parliament meets, on the basis of consensus between the various political parties. He also needs the green light from regional and international powers — currently Saudi Arabia, the United States, France and Iran.

Has the presidential election ever been decided at the ballot box? Essentially only once, in 1970: on Aug. 17, Sleiman Frangieh was elected by a single vote over the Chehabist candidate Elias Sarkis.

This story originally ran in French in L’Orient-Le Jour, translated by Joelle Khoury.