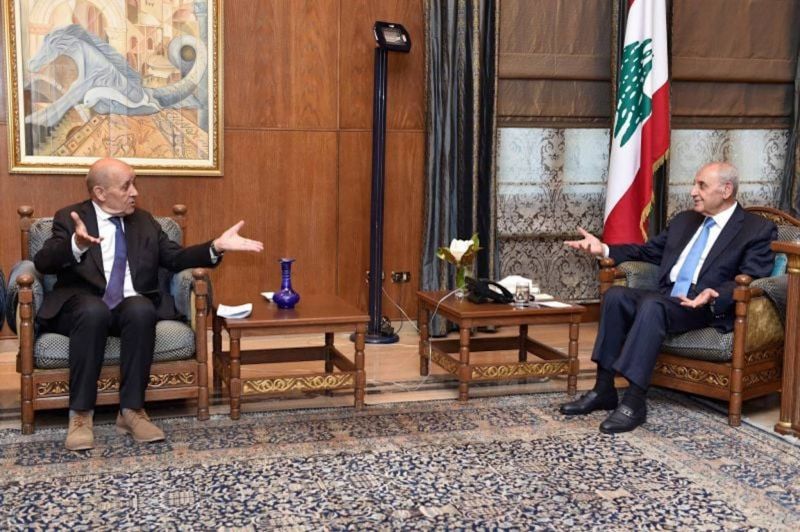

Jean-Yves Le Drian, France's special envoy for Lebanon, meets House Speake Nabih Berri, Beirut, June 21, 2023. (Credit: AFP)

Your nomination as the envoy to Lebanon of the French President is a welcome development that can help tip the scales in favour of local efforts to recapture the state, restore the integrity of public institutions, and reform the fundamentally illiberal status quo.

With the stakes so high, French foreign policy in Lebanon is in urgent need of a reset. As your visit to Beirut comes to a close, there is a brief window of opportunity to build upon your tour’s momentum and help break the presidential impasse. To succeed where recent French efforts in Lebanon have not, Paris must realize its role is not that of a mediator among ‘equal parties’ but rather a guarantor of democracy and a check on spoilers, bolstered by their regional patrons.

Only two days after the Beirut blast on August 4, 2020, President Macron made a spectacular appearance in the ravaged areas of the capital city, where he was enthusiastically greeted by hundreds of young Lebanese who were on the streets both protesting to bring down the government and picking up the rubble left behind by the explosion. “You are our only hope,” protestors told him. He responded by making ambitious promises, calling for an international investigation into the blast and promising sanctions on those who continue down the path of blocking much-needed reforms. He also gave Lebanese political leaders, whom he convened at the French embassy, 15 days to form a government that would implement the reforms.

Four years later, President Macron’s vision has not come to pass: no reforms have been enacted, the domestic investigation has been sabotaged by Hezbollah and its allies, and France has yet to impose sanctions. Instead, the Lebanese have found themselves bewildered learning that France considered supporting a presidential candidate who embodies everything President Macron promised he would stand against.

Lebanon's political landscape has been dominated by Hezbollah since 2008 when it coerced and co-opted its local rivals into submission and was rewarded with the Doha Accords that established “consensus” on its terms. As a result, the status quo in Lebanon is defined by a hierarchy of power that positions Hezbollah at the top, while a corrupt political class scavenges off the spoils of the state that fall outside the strategic interests of Hezbollah and its regional patron, Iran. It is this consensus between mafia and militia, which we outline in more detail elsewhere, that is at the root of Lebanon’s failure and risks transforming Lebanon not just into a failed state, but a quasi-authoritarian one, that will irreversibly cut off Lebanon from the region and global economy and reverse decades of locally-led and internationally supported efforts to build a democratic, stable country.

Hezbollah does not seek compromise but, rather, a veto on any challenge to its power. Hezbollah's pursuit of veto power to safeguard its authority is in blatant disregard of the constitution and democratic process. It is solely dependent on the strength of its weapons and the unbridled freedom it has enjoyed due to years of impunity. When Hezbollah cannot attain its objectives democratically, such as imposing its presidential candidate when it lacks a majority in Parliament, it forces political paralysis. Its ability to do so through unchecked coercive means, fuels the gradual decay of the state, formal economy, and the fundamental concept of citizenship. Hezbollah’s ostensible success, bolstered by a haunting legacy of impunity, serves as a blueprint for Iran, particularly with its armed proxies in Iraq, and threatens the demise of democracy in Lebanon and the Levant. The struggle for Lebanon holds great significance, not only for the preservation of democracy and stability within the country but also for the larger geopolitical landscape in which Iran's hegemony and authoritarian vision are being challenged.

Despite the odds, Lebanon’s opposition and the Christian allies of Hezbollah largely rallied around a technocratic presidential candidate, providing him with a majority of Christian and a plurality of Lebanese support. It is certainly up to the Lebanese to elect their president, but it must be conveyed to Hezbollah and Iran in coordination with the US and regional partners that the threat of assassination or any other forms of political violence — as surfaced shortly before the election — is a red line.

The contest for the presidency is no quid pro quo, but rather, a key component of the package deal needed to stop Lebanon’s descent into a failed, authoritarian state. Lebanon needs a president, prime minister, and government committed to Lebanon’s sovereignty, the reforms needed to implement an IMF deal, and that can restore meaningful Arab relations that are the lifeline of its economy. France need not carry this mantle alone. Riyadh’s growing leeway with Iran may facilitate reducing obstruction of the presidential file. Coordination between European and American partners will also strengthen the credibility of the threat or use of targeted sanctions on spoilers. After all, sanctions have proven effective in preventing Gebran Bassil from running for president or in ensuring the Speaker of the House, Nabih Berri, held a presidential election session, albeit with a clear intent to spoil the necessary second round of voting. The credibility of an effective sanctions policy requires disassociation from caretaker prime minister Najib Mikati, whose noticeable proximity to the Élysée despite his failed legacy, continues to open France to accusations of colluding on business issues.

Acting in unison, members of the quintet — France, the US, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Egypt — must make explicit to those obstructing the election of a president, namely Hezbollah and Parliament speaker Berri, that the quintet will not back “consensus” by vetocracy as defined by the Doha Accords; the only formula on the table is for all parties’ compliance to the rules of the game outlined in Lebanon’s constitution.

We are living in times of tremendous uncertainty, where words like freedom and justice, once taken for granted, are redefining the language of international relations. What is Lebanon, like France, if not an idea? All we ask is that you trust in and commit to that idea that connects our two countries and reject the more expedient but self-defeating path of a false, illiberal consensus. So, democracy lives; so, democracy dies.

Fadi Nicholas NassarUS-Lebanon Fellow

Middle East Institute

Saleh el Machnouk

Non-Resident Scholar

Middle East Institute

This opinion originally ran in French in L’Orient-Le Jour.