Lebanese-Ukrainian soldier Hussein Medhi in May 2022. (Credit: Hugo Lautissier)

If it weren’t for the bombardments, the destroyed houses and the band of soldiers stationed on the outskirts, the small village of Pryshyb in the Donbass region would be a little paradise, with its spring sunshine, green hills and clearly-defined gardens.

It’s May 2022. Ten kilometers to the west, the town of Lyman, a major rail hub in the Donetsk region, is about to fall to the Russian army after weeks of bitter fighting.

It’s just weeks into the war that broke out at the end of February, but the peaceful village has already turned into a disaster zone, deserted by most of its inhabitants. Those who have stayed, mostly the elderly, come and go without reacting to the sound of the ongoing bombardments.

Near an abandoned house, a few soldiers regain strength before returning to battle. One of them approaches, smiling but tired. “I know what you’re thinking, you come across a Lebanese in the Donbass every day.”

In a battalion of volunteers

Hussein was not one of these foreign soldiers, parachuted far from home into a hostile region he knew nothing about. He was born 70 kilometers away, in the village of Konstantinovka, where his father, a Lebanese national from Jbeil, met his Ukrainian wife while they were studying at dental school.

Since then, Hussein, 38, had come a long way, studying electronic engineering at the Lebanese University before becoming an engineer, working in Saudi Arabia and then Moscow, without ever breaking ties with Lebanon.

That day, in the desolate village in Donetsk, he recalled Lebanon, a land of contrasts: bars and restaurants, churches and mosques and, above all, the beach in Jbeil. It all seemed so far away.

Lebanon was where he had been when the Russian invasion of Ukraine began to look inevitable. Just months earlier, surrounded by his family, he had buried his mother, who died of cancer in December 2021.

When in mid-February 2022, American intelligence reported a major Russian offensive on Ukraine, Hussein took the first flight to Kiev, leaving behind family, friends and a promising engineering career.

“I’m fighting for my freedom and for these people who have lost their homes, everything they've made over the years. Women and children have been killed: in Bucha, Mariupol. I'll never forgive the Russians for that,” he told L’Orient-Le Jour in Pryshyb in May 2022.

From the very first day of the war, he enlisted in the Territorial Defense forces, answering the call of Ukrainian President Vladimir Zelensky.

In this battalion of volunteers, almost all the fighters had no military experience. Yet, a week later, he was already on the front line in Donbass.

According to the last figures he gave his family, only 18 of the 60 or so soldiers in his battalion were still alive at the beginning of 2023.

‘It was this war that killed him’

Hussein Mehdi died at the age of 38 in early February this year, almost a year after his arrival at the front. Unlike his fellow soldiers, he did not die with weapons in his hands. He succumbed to heart sclerosis, related to hypertension problems, in the last active hospital in Konstantinovka.

His father, Nizar Mehdi, had spoken to him on the phone a few days earlier. His face had swollen, and he immediately knew there was a problem. A few days later, Hussein stopped answering the phone. It was all over.

“It was this war that killed him. Hussein didn’t have his medication over there. The stress, the fighting, the explosions, the sleepless nights — all that explains his death,” he said.

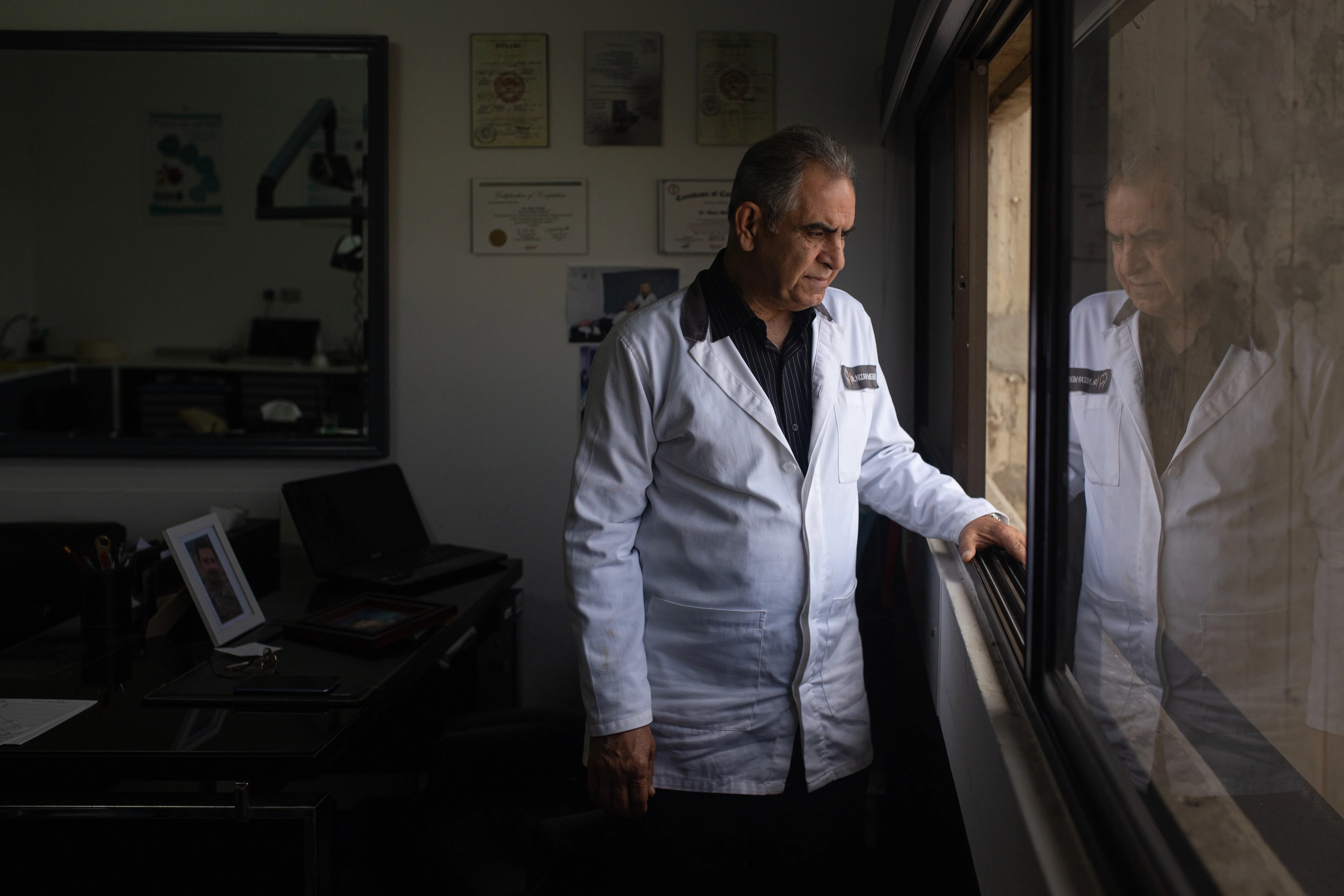

Nizar Mehdi is now alone, after the death of his wife and then his son. Here he is, in his office in Jbeil. (Credit: Hugo Lautissier)

Nizar Mehdi is now alone, after the death of his wife and then his son. Here he is, in his office in Jbeil. (Credit: Hugo Lautissier)

These days, in Jbeil, Hussein’s father is busy with patient after patient. In his small dental office in the town center, he has eased his grief through work. He is at his practice in the morning, then he receives patients at another practice in the afternoon, as well as at General Security.

“It’s the instinct at work. It’s the only thing that keeps me going. I lived 40 years for him, to see him married and see his children grow up. Now I’m alone when I come home, and the walls don’t talk,” he said.

When Hussein told him about his decision to leave for Ukraine, Nizar at first tried to dissuade his son. Hussein replied that Nizar would have done the same at his age to defend Lebanon. With a heavy heart, the dentist accepted his choice.

In the waiting room, patients come and go, but time stands still for the dentist. He reviews the photos of his missing family members: Irina, the woman who shared his life with for 43 years, and now his son, about whom he still struggles to speak in the past tense.

In the last photo he sent him, Hussein was bedridden in hospital, a catheter stuck in his forearm. In the image, he is making the V of victory with his fingers.

“He was a beautiful person, an artist in the way he sees things. He brought emotion and heart to everything he did. He gave a lot,” said Nizar.

‘I need a quiet life’

In our interview in May 2022, Hussein told us how he saw his life after the war. He planned to stay in Ukraine, in the region where he was born.

“I may buy a small house with a plot of land, like in this village, raise animals and fish. I need a quiet life. I’m an engineer before being a soldier. I just want to take care of my family, have a wife, children, and why not bring my father back here when the war is over.”

Desolation in Ukraine. (Credit: Hugo Lautissier)

Desolation in Ukraine. (Credit: Hugo Lautissier)

After Hussein’s death, Nizar tried to repatriate his son’s body to Lebanon to be laid to rest beside his mother. The army told him that the situation is presently too dangerous and that he could do so when the war ends.

Hussein was finally buried in Konstantinovka, in the cemetery where his grandparents are buried.

“Maybe he’s happy there after all, in the land he loved, with his mother’s parents,” Nizar said, asking, “How long do I have to live? One year, four years, 10 years? Hussein will be resting alone. What’s the difference between here and there?”

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury.