Rima Husseini’s husband, Ali, a Baalbeck native and son of the late former Parliament Speaker Hussein Husseini, bought the Palmyra in 1985 as a sort of passion project, she says. But it was the height of the Lebanese Civil War, and the hotel was already past its heyday of celebrity soirées once fed by the famed yearly Baalbeck Festival across the road. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

BAALBECK — Rima Husseini floats in chic platform boots through dozens of quiet rooms in the Palmyra Hotel, which she co-owns with her husband, just across from Baalbeck’s ancient Roman ruins.

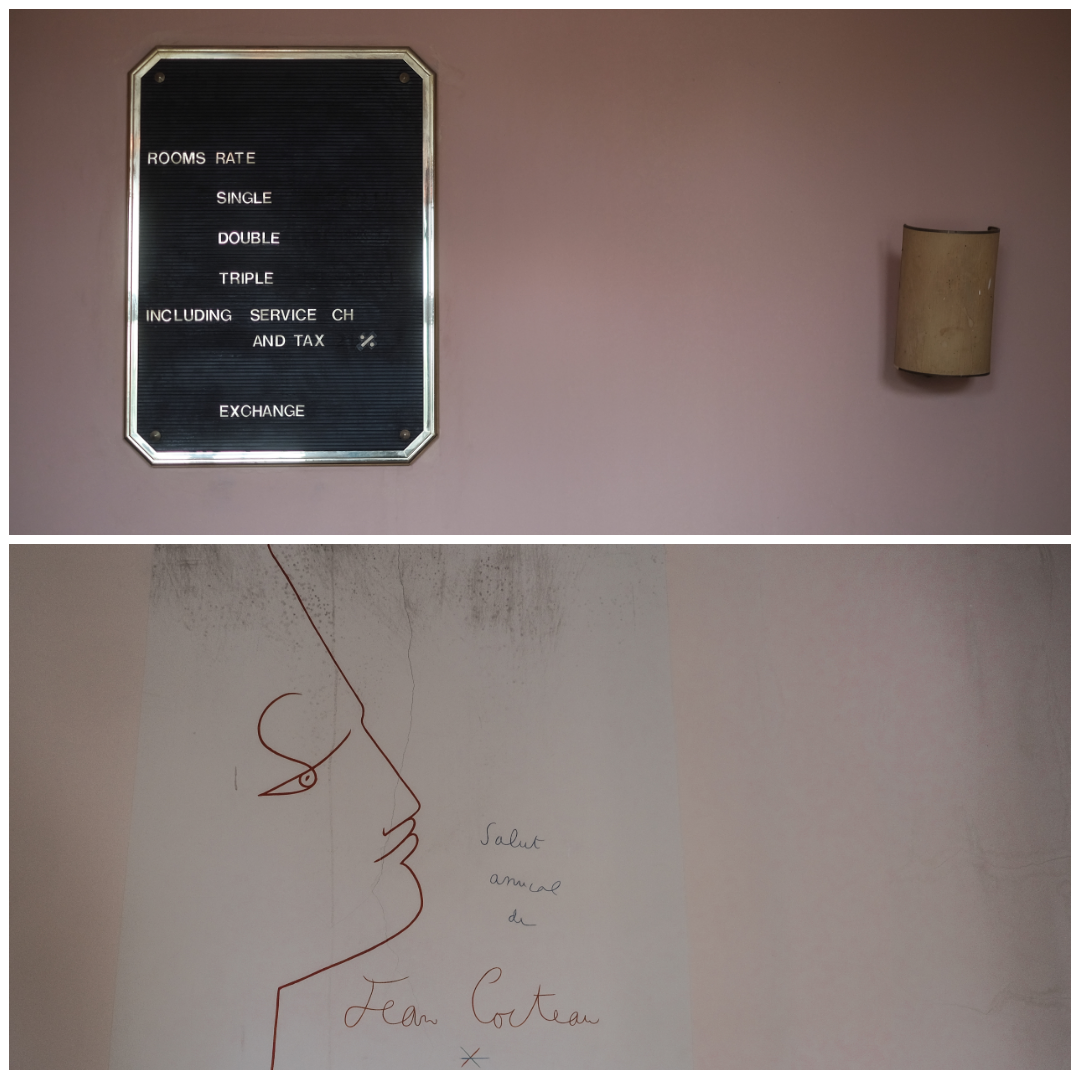

There are grand high-ceilinged hallways, a bedroom adorned with whimsy curlycue drawings by the French Dadaist poet Jean Cocteau, a kelly-green salon furnished with ancient plush chairs for guests who don’t seem to materialize. Husseini says she picked the green paint herself.

She breathlessly straightens white crochet bedspreads in the guest rooms as she goes, and fixes Persian runner carpets warped by time.

“That’s the manager in me,” she tells L’Orient Today one weekend afternoon in April.

A reception room off the Palmyra’s main entrance. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A reception room off the Palmyra’s main entrance. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Husseini’s once-glamorous hotel was built in 1874 by a Greek businessman from Istanbul who noticed pilgrims looking for a place to rest in style on the road to Jerusalem.

It soon became part of a triad of storied Grand Budapest Hotel-esque properties — including Aleppo’s Baron Hotel and the Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo — from the same era that hosted royalty, poets and pop stars.

The Palmyra is the only one of the three that remains – mostly – intact.

Husseini’s husband, Ali, a Baalbeck native and son of the late former Parliament Speaker Hussein Husseini, bought the Palmyra in 1985 as a sort of passion project, she says. But it was the height of the Lebanese Civil War, and the hotel was already past its heyday of celebrity soirées once fed by the famed yearly Baalbeck International Festival across the road.

“Lebanon hits you in the head,” says Rima Husseini, who co-owns the Palmyra Hotel (shown above) with her husband Ali. “One of the main challenges is trying not to close doors, and keeping financial operations going in spite of so many difficulties historically.” April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

“Lebanon hits you in the head,” says Rima Husseini, who co-owns the Palmyra Hotel (shown above) with her husband Ali. “One of the main challenges is trying not to close doors, and keeping financial operations going in spite of so many difficulties historically.” April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The star-studded property collected dust as the country around it changed.

In a city so close to the Syrian border and given Lebanon’s past several years of economic freefall, Husseini says the Palmyra Hotel has become a difficult draw.

There are also the negative stereotypes of Baalbeck as a sort of Hezbollah-run Wild West rife with firearms, she laments.

Most of all, though, is the sheer lack of electricity in Baalbeck, where state neglect means at most two hours of daily government-supplied power.

The Palmyra’s 17 solar panels, which workers installed last year. The system helps power 24-hour lighting in the hotel, which Husseini hopes will draw in more guests as tourism in Lebanon bounces back. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The Palmyra’s 17 solar panels, which workers installed last year. The system helps power 24-hour lighting in the hotel, which Husseini hopes will draw in more guests as tourism in Lebanon bounces back. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Now Husseini is pinning hopes on a more recent trend to emerge from Lebanon’s three-year economic crisis and chronic electricity blackouts that could keep her ailing business afloat: solar energy.

Last year, the hotel installed 17 solar panels on the roof to the tune of $20,000, including materials and labor.

It’s a major investment for a hotel that Husseini says has been operating at a loss for years, even as rooms go for a (relatively) pricy $75-$90 per night. They also still pay nearly $2,000 per month in private generator fees to keep other amenities at the hotel running, according to Husseini.

A sign in the Palmyra’s check-in room that once displayed the daily room rates sits empty. A drawing by French Dadaist poet Jean Cocteau, who stayed at the Palmyra. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A sign in the Palmyra’s check-in room that once displayed the daily room rates sits empty. A drawing by French Dadaist poet Jean Cocteau, who stayed at the Palmyra. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

So far, she says, it’s paying off somewhat – as tourism slowly bounces back, the hotel can now run 24/7 lighting and pay a bit less of its profits toward simply keeping the generator-powered heat on. And New Year’s Eve a few months ago saw a full house, according to Husseini.

She’s not the only one in the area betting on solar energy.

Solar is catching on across Baalbeck, hotel staff and residents say, as the area is starved for electricity. Those who can afford it are buying rooftop solar panels in droves. Dozens of solar installation companies line the highway into the city.

“This region is one of the best in Lebanon for solar,” Rony Karam, president of the Lebanese Foundation for Renewable Energy (LFRE), tells L’Orient Today. The LFRE did a survey of the area, he says, and found “high irradiation, dry, flat land and plenty of public, non-agricultural land available.”

Solar-powered lighting at the Baalbeck ancient ruins. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Solar-powered lighting at the Baalbeck ancient ruins. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Five minutes down the road, two young installation workers at a solar panel shop say business is booming. They’ve picked up freelance installation work across town the past couple years.

Husseini is hoping the increased power supply from the solar panels – which go, crucially, to keeping the lights on during Baalbek’s long winter months – could draw guests back to the storied hotel.

Still a touristic destination?

So far for the Palmyra, there seem to be more travelers coming through, says the hotel’s Syrian sous-chef Rabih Sle’ah, and the solar panels help keep the lights and heating on for them. He lives on-site, so he helped oversee installation of the solar panels last year.

The UNESCO-listed Roman Temple of Bacchus in Baalbeck’s ancient ruins, located just across the main street from the Palmyra Hotel. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The UNESCO-listed Roman Temple of Bacchus in Baalbeck’s ancient ruins, located just across the main street from the Palmyra Hotel. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The same Saturday L’Orient Today pays its visit, a few Danish tourists arrive for a one-night stay. Another family of four shuffles in at one point in the late afternoon, signing in at a massive old check-in desk just off the main salon.

Despite Lebanon’s present-day woes, Baalbeck is still drawing in some tourists.

A short walk from the Palmyra is the bright blue and golden-tiled Sayyidet Khawla shrine, where dozens of Muslim faithful gather early that afternoon, some of them from outside Baalbeck. They’re here to pray, recite Quran verses and visit the medieval tomb said to belong to one of Muhammad’s great-granddaughters.

A few vans of Spaniards and Portuguese arrive with tour guides at the Stone of the Pregnant Woman across the road, the site of a Roman stone monolith said to have been part of the ancient Baalbeck site.

A room key and the bedroom where French Dadaist poet Jean Cocteau slept when he stayed at the Palmyra in the 1960s. Now it contains a handful of his drawings. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A room key and the bedroom where French Dadaist poet Jean Cocteau slept when he stayed at the Palmyra in the 1960s. Now it contains a handful of his drawings. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

And, of course, there are the towering, columned ancient ruins of Baalbeck, today watched over by a few newly installed solar panels on metal poles.

‘Sabah slept here’

But today is quiet at the Palmyra. Weaving in and out of the vast hallways is a skeleton crew of mostly elderly staff who have been there for decades.

Among them is a bespectacled 76-year-old Menha Abbas, known by everyone Abu Ali, who wears a knit sweater over a neat collared shirt and tie as he cleans the bedrooms.

He’s been working at the Palmyra since he was a young man in the late 1960s. Since then Abu Ali has started a family, served international celebrities and lost part of his hearing in a wartime bombing attack near the hotel.

Abu Ali, now in his 70s, has been an employee of the Palmyra since 1968. He says his happiest memories of the hotel’s heyday are the “silent moments” as famous musicians like Fairouz, Sabah and Nina Simone shuffled downstairs for drinks and grand dinner parties, leaving him to tidy their rooms. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Abu Ali, now in his 70s, has been an employee of the Palmyra since 1968. He says his happiest memories of the hotel’s heyday are the “silent moments” as famous musicians like Fairouz, Sabah and Nina Simone shuffled downstairs for drinks and grand dinner parties, leaving him to tidy their rooms. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Those days are now a distant memory.

Downstairs, Mira, a stray orange cat from the front garden, wanders inside for an afternoon nap. The hotel is still rarely at full occupancy, but some 25 equipped rooms stand at attention anyway.

Abu Ali emerges from one of them, now donning a timeworn suit jacket over his sweater.

He says his happiest memories of the hotel’s heyday are the “silent moments” as famous musicians like Fairouz, Sabah and Nina Simone shuffled downstairs for drinks and grand dinner parties, leaving him to tidy their rooms.

The Palmyra Hotel’s dining room was once the stage for grand dinner parties of celebrities attending the Baalbeck International Festival just across the road. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The Palmyra Hotel’s dining room was once the stage for grand dinner parties of celebrities attending the Baalbeck International Festival just across the road. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

He walks down a nearby hallway to a two-bed room where Sabah used to stay.

“She was kind, she used to talk with the staff,” Abu Ali remembers. “Ms. Fairouz was more official – she didn’t mix with people except to ask for services.”

Steps away, the dining room’s dozens of wooden chairs sit empty.

A worker tends to the check-in desk at the Palmyra Hotel. Only a couple of the hotel’s 25 rooms are occupied today, co-owner Rima Husseini says, though New Year’s Eve saw full occupancy. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A worker tends to the check-in desk at the Palmyra Hotel. Only a couple of the hotel’s 25 rooms are occupied today, co-owner Rima Husseini says, though New Year’s Eve saw full occupancy. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A collective memory

For now, most of the guests are European tourists here for the history, Husseini says. There are also the scattered few backpackers who take up temporary residence in the cheaper rooms on the unheated first floor. Those ones don’t have private bathrooms, she says.

Travelers wanting a bit more style than the Palmyra’s art-deco-era furniture and chipped paint now stay at the nearby L’Annexe, a 19th-century home the hotel’s owners bought nearby.

That property has been run by L’Hote Libanais, a high-end, fashionable guesthouse company, for the past six years.

Rima Husseini is one of the co-owners of the Palmyra Hotel in Baalbeck and serves as its manager. She’s also a lawyer and lecturer in Beirut. April 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Rima Husseini is one of the co-owners of the Palmyra Hotel in Baalbeck and serves as its manager. She’s also a lawyer and lecturer in Beirut. April 8, 2023. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Husseini has, for now, refused to let L’Hote Libanais take over the main Palmyra building, too – though she says the company’s founder did propose the idea.

“The Palmyra is not a guesthouse,” says Husseini. “That would ruin its image.”

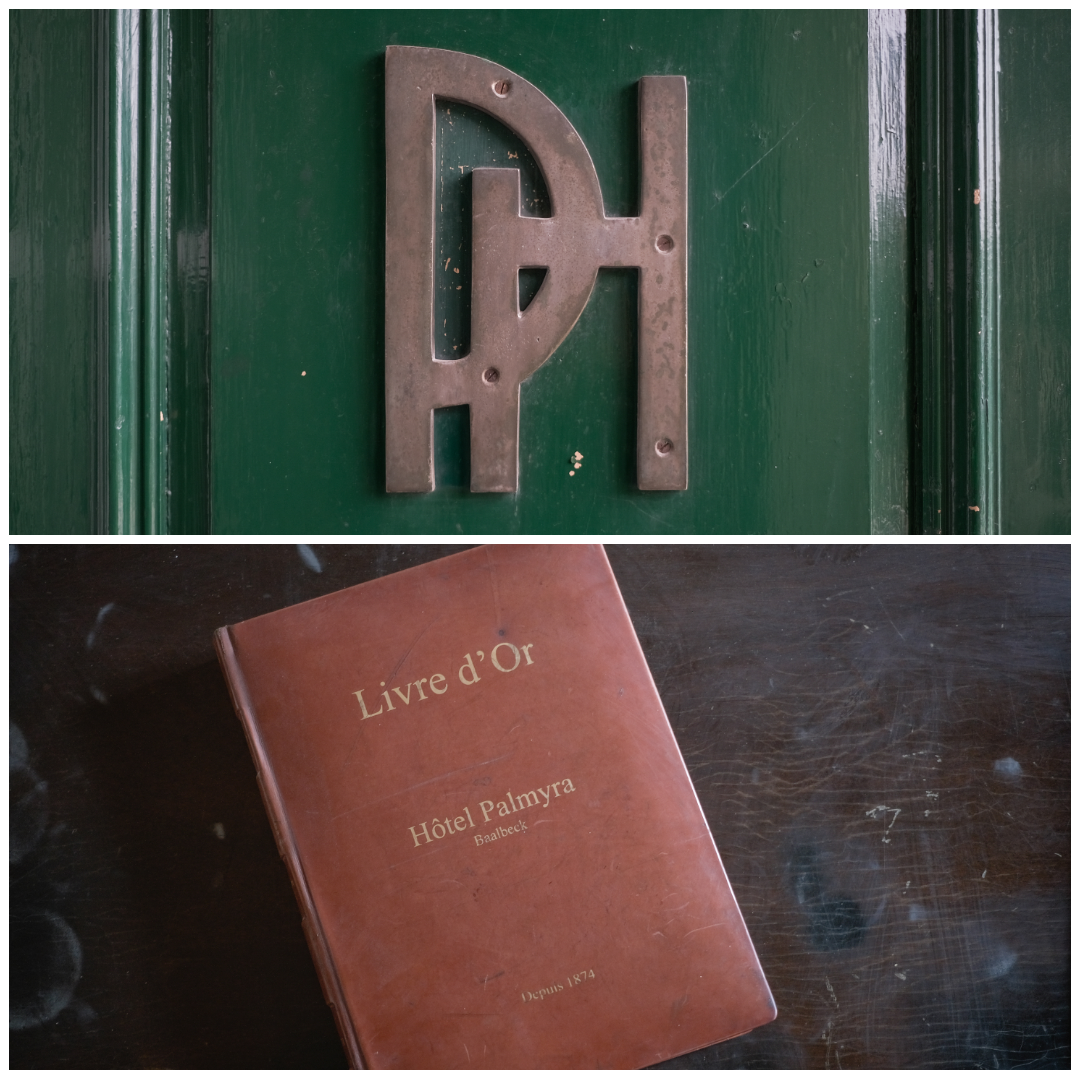

“We aren’t hoteliers,” she admits. But she’s well versed in the hotel’s history and says she’s determined to keep it running as a heritage site of sorts. “It’s a place of collective memory.”

“I see this hotel as a museum,” says Rima Husseini of the Palmyra, on April 8, 2023. Above are a logo and guestbook inside the hotel. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

“I see this hotel as a museum,” says Rima Husseini of the Palmyra, on April 8, 2023. Above are a logo and guestbook inside the hotel. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Nearby, in one of the entry rooms, sits a guestbook dating to the 1990s, when the Baalbeck festival finally started once again post-civil war, welcoming acts like opera singer Plácido Domingo. Filed away elsewhere in some unseen closet is yet another, listing the names of stars who slept and partied here reaching back to the late 1800s, all beneath its grand, cracked staircases.

“I keep saying that we are the guardians of the place,” says Husseini.

“No one has the right to touch these stones except time.”

The ruins of Baalbeck seen with still snow-capped mountains in the background. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The ruins of Baalbeck seen with still snow-capped mountains in the background. April 8, 2023. (João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

- A culinary journey from Beirut to Brussels cooks up tradition, love and teta's recipes

- In Tripoli’s Bab al-Tabbaneh and Jabal Mohsen, ex-rival fighters light up former frontlines with solar energy

- Savvy Element: Finding a niche in the local self-care and home-care market, despite Lebanon’s crisis