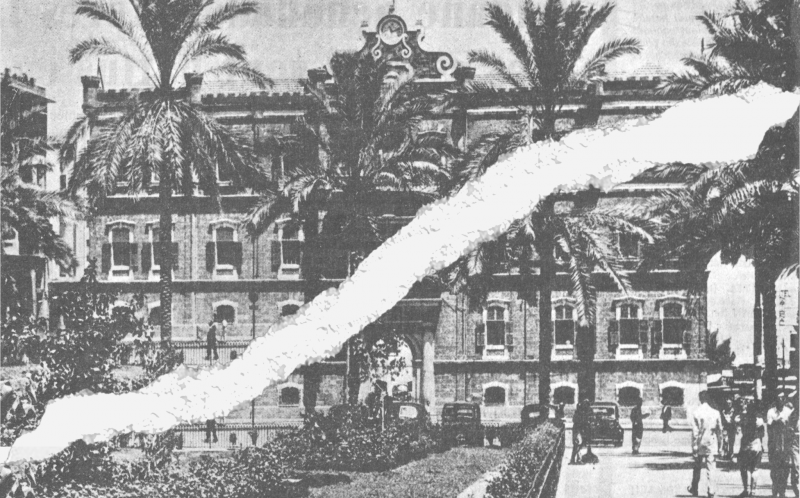

Created in 1863, the municipality of Beirut was split in two from 1908 to 1911. (Credit: L'Orient-Le Jour archives/Illustration by Guilhem Dorandeu)

It is a period erased from Beirut’s consciousness; only the history books still have the memory.

This piece of information, in the wrong hands, could easily be distorted given its potential for being misunderstood.

At a time when some Lebanese political forces are calling for a partition of the capital, a brief historical detour provides valuable context to understand that the debate is neither new nor convincing.

Just over a century ago, Beirut residents witnessed a short-lived experiment that, officially, aimed to improve local administration by dividing the municipality’s services.

By the governor’s decision, the municipality was split into two.

Starting in 1908, the western part of the city was administered by a Sunni president named Mounih Ramadan, while the eastern districts were managed by a Greek Orthodox official named Boutros al-Dagher.

The municipality, a new and daring institution, was introduced in the region for the first time in Beirut in 1863, and then in Deir al-Qamar in 1864— offering citizens the prospect of fair governance and democracy.

At a time when the Ottoman Empire was seeking to modernize itself, the municipality provided an unprecedented local administration, while also offering a degree of autonomy from the central power.

“When the Allies occupied Beirut in October 1918, they were faced with the demands of the city’s municipal council,” wrote historian Carla Eddé in a 2014 article published in Cahiers du Cermoc.

In the eyes of the Ottoman legislator, it was only natural that the size of this avant-garde institution should be proportional to that of the urban fabric it administered. An 1877 Ottoman law authorized one municipality for every 40,000 inhabitants of a city. For instance, Damascus had four municipalities between 1905 and 1909.

In Beirut, the debate about a duplicate municipality accompanied the city’s growth.

“Beirut was entitled to two municipalities from the moment its population exceeded 80,000,” said Jens Hanssen, an associate professor of Arab Civilization, Middle Eastern and Mediterranean history at the University of Toronto, to L’Orient-Le Jour.

However, it was not until 1908, during an internal dispute between Sunni officials, that the decision was finally made.

The experiment quickly turned sour as the same rivalries that plagued the old municipality applied to this new configuration.

“The two municipalities competed in the worst possible way,” reads an archival document cited by Hanssen in his book, Fin de Siècle Beirut: The Making of an Ottoman Provincial Capital (Oxford, 2005).

Moreover, the presuppositions on which the partition was based — that multiplying municipal offices would provide better service — proved false.

“The Ottoman state concluded that it was pointless to continue with the division,” Eddé told L’Orient-Le Jour. “It did not produce any results, on the contrary, the division began to cost much more.”

The unity of the city was re-established in 1911, on the orders of the new governor. The page was turned, and the experience was relegated to the archives of history.

Unspoken

One hundred and eleven years later, the idea was reintroduced.

In July 2022, three MPs from the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) presented a bill providing for a municipal split between the Christian-majority East and the Muslim-majority West, with a capital-wide mega council to oversee the whole city.

Again, the official reason is technical: “To improve services to citizens and allow for good management, the municipality must be divided in two,” FPM MP Nicolas Sehnaoui told L’Orient-Le Jour.

Though under the guise of decentralization, the project cannot hide its sectarian aims. For many observers, the proposal is a thinly-veiled attempt to institutionalize a confessional logic inherited from the civil war.

The project threatens to “take us back 30 years,” said Waddah Sadek, an MP affiliated with the protest movement, to L’Orient-Le Jour.

Thirty years, maybe even more.

From 1908 to 2022, the project to divide Beirut is full of communal undertones that have not survived the practical test.

“Behind the idea of greater efficiency, there is an unspoken fact: from the beginning of the 20th century, some accuse the municipality of taking more care of the western neighborhoods," explained Eddé.

The western part of the city is predominantly Muslim, with a significant portion of Christians residing there until the 1970s.

Today, as in the past, the community tug-of-war for control of the capital is precisely what could lead to its necrosis.

“This proposal defies all the knowledge we have about urban planning. It is a populist discourse at a low cost. Beirut is tiny, and ungovernable because it is dissected into small units,” says Mona Fawaz, professor of urban studies at AUB and co-founder of the Beirut Urban Lab.

“On the contrary, the administrative area should be enlarged, not reduced.”

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.