Graffiti in the streets of Beirut. (Credit: Joao Sousa/L'Orient Today)

“It came down to a few minutes, the travel time ... I didn’t make it on time.” Ali Kalot’s voice broke.

On Wednesday March 1, at 7:50 am, Kalot received a text message from his brother-in-law M.S., saying that because he was “too tired of life,” he was going to end it in a few minutes.

“I kept calling him, he didn’t answer anymore,” said Kalot, who rushed to stop him.

But he was too late. He arrived to find the body of the 30-year-old man lying lifeless in front of his home in Deir Zahrani, South Lebanon.

M.S. was a father of a two-and-a-half-year-old girl and stepfather to a nine-year-old boy. He left his job in the army due to the economic crisis and was trying to find another way to make ends meet, without success. On edge, he had left home to live with his parents for the last two weeks. On the last Sunday before his death, the two men talked about the 30-year-old’s plans to open a bakery in Sour.

“He told me he was going to start on Saturday... I don’t get it,” Kalot said.

The families of the other suicide victims, H.M., from the village of Zrarieh and M.I., from Wardanieh, told similar stories. The family of another victim from Zahle, preferred not to speak about the incident.

A security source told L’Orient-Le Jour that “everything suggests that it was suicide in all four cases, although the investigation is still ongoing.”

On Thursday, P.S., 62, ended his life after posting a message online explaining why. His reasons were linked to the financial difficulties he had been facing.

The press and social media portrayed these men as victims of the seemingly unending economic crisis.

M.I. was an employee at the courthouse of Saida and the father of two children. A person close to the man said that he was drowning in debt. Before taking his own life, he had written a letter to a friend asking his relatives and his village to forgive him.

The same is true in M.S.’s case. “According to the first elements of the investigation, his action was linked to his financial situation,” said Hassan Zawawi, mayor of Deir Zahrani.

Apparently, this was not the case for H.M. who, according to his brother, “had enough to live on.”

A.A.H, age 40, had money-related problems and debts despite coming from an influential family in Zahle, according to L’Orient’s correspondent in the area.

Nearly 75 percent of Lebanese under constant stress

This wave of suicides, which took place within a week, has caused a stir in Lebanon.

“It appears that suicide has become the new norm in Lebanon,” wrote one Twitter user.

“About 10 percent of suicides can be attributed to significant events, such as severe financial loss, rather than ongoing socio-economic distress,” said Mia Atoui, co-founder and president of Embrace, a leading mental health NGO in Lebanon.

Will the suicide rate continue to increase as the situation in Lebanon continues to spiral downwards?

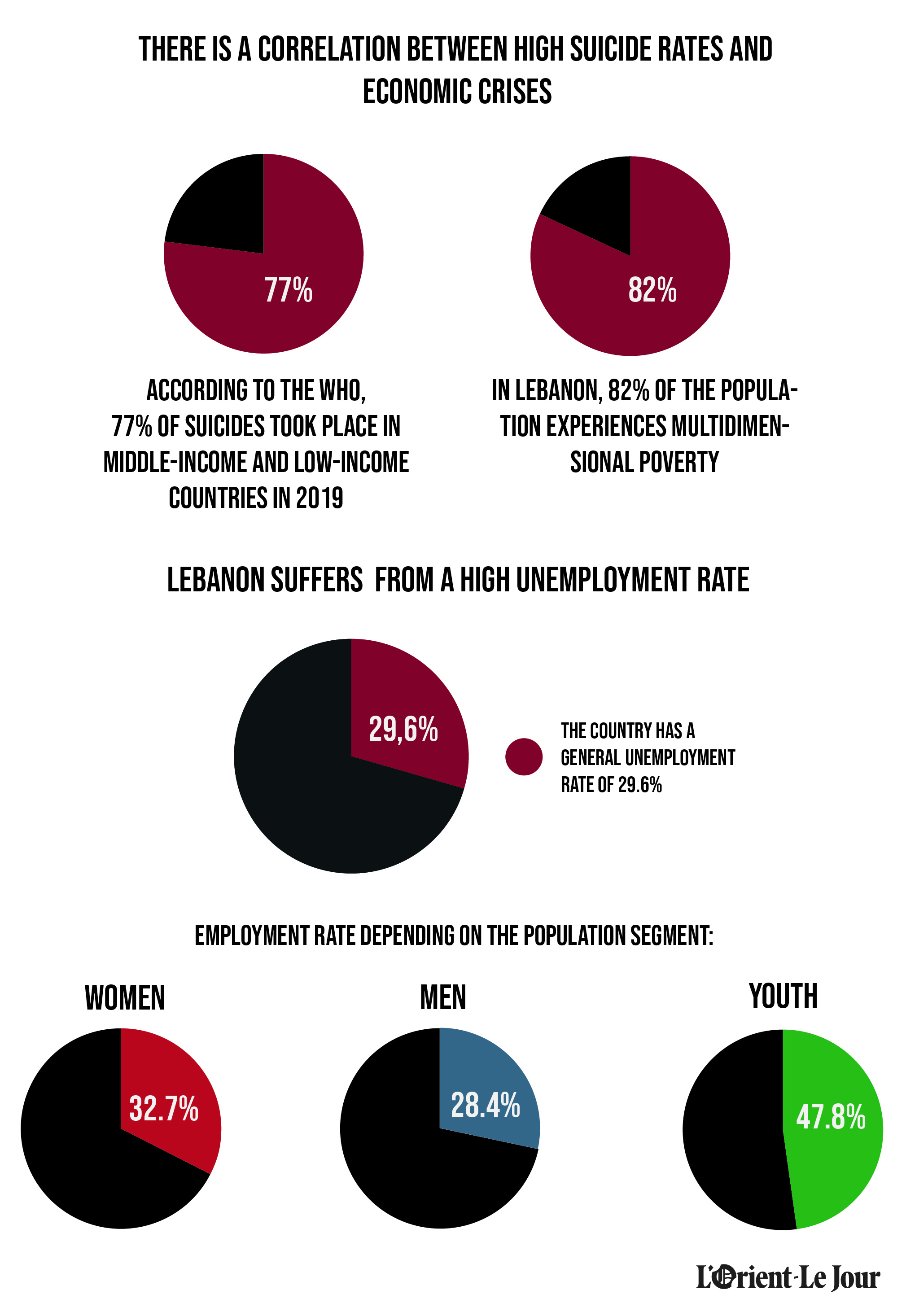

A number of scientific research studies conducted in different countries have shown a relation between higher suicide rates and the economic situation. Published in 2015 in the World Journal of Psychiatry, a study titled Systematic Review of Suicide in Economic Recession cited Greece as an example. Between 2008 and 2011, a “significant and positive” correlation was found between the suicide rate and unemployment and debt.

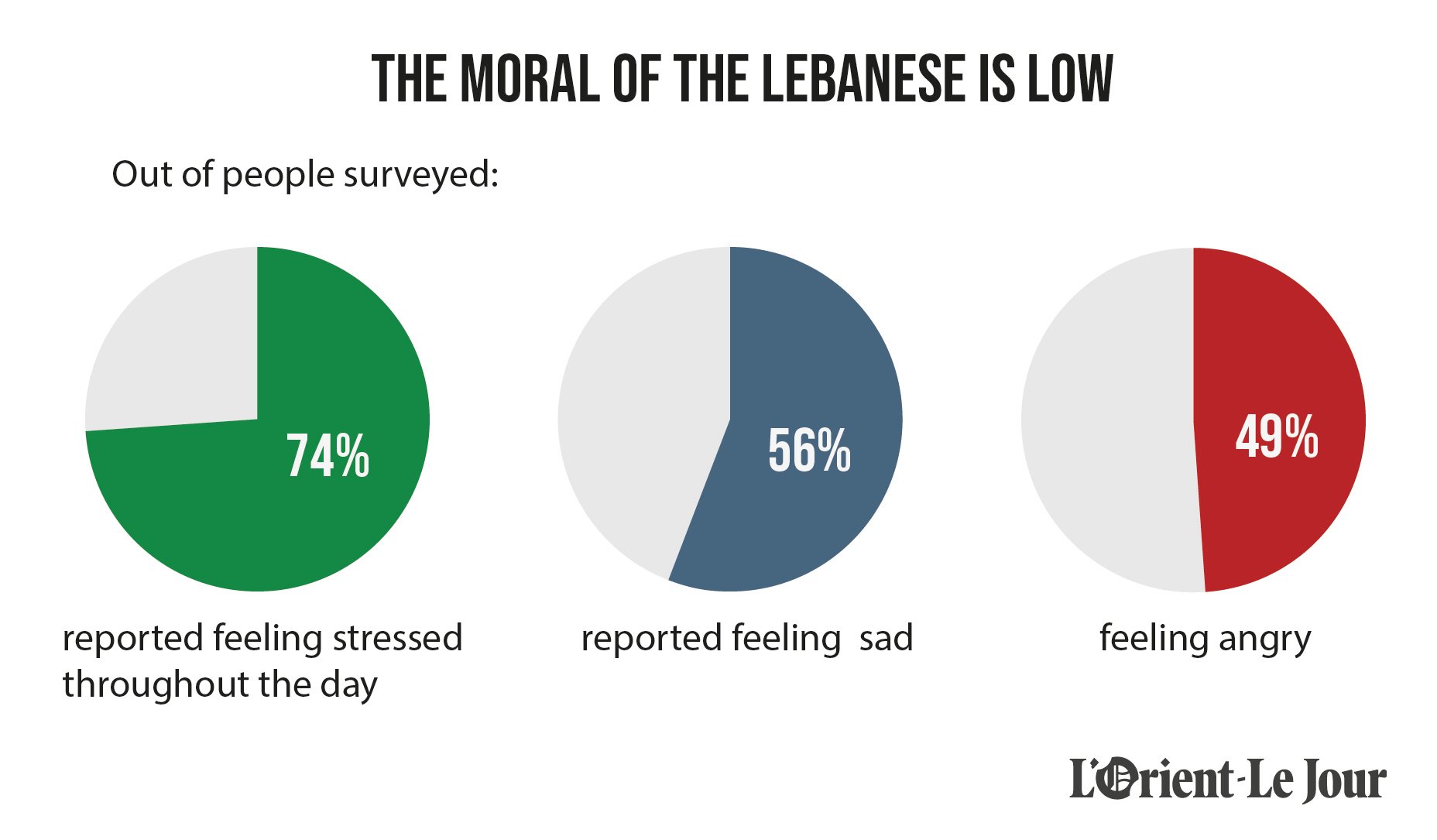

According to the Central Administration of Statistics (CAS) and the International Labour Organization (ILO), Lebanon’s unemployment rate in January 2022 was 29.6 percent, with 32.7 percent of women out of work compared to 28.4 percent of men. The unemployment rate of youth was 47.8 percent. In a 2021 Gallup report, 74 percent of people surveyed expressed that they were stressed for a “substantial part of the day,” 56 percent felt sad and 49 percent felt angry.

Albert Moukheiber, a clinical psychologist and neuroscientist, said an increase in suicide cases is to be expected. “In Lebanon, the crisis is not only continuing, but it is also getting worse. The population cannot see the end of the tunnel.”

According to a 2019 World Health Organization report, 77 percent of suicides took place in middle-income and low-income countries. In Lebanon, 82 percent of the population now lives in “multidimensional poverty,” said the UN Economic and Social Commission for West Asia (ESCWA) in a 2021 report. Psychological stressors seem to increase as inflation continues to rise.

“These factors can affect pre-existing mental disorders or trigger them,” said Atoui, who added that anxiety disorders and the feeling of powerlessness do not necessarily translate into an increase in suicides. “There are usually predispositions [somber mood, anxiety, depressive symptoms...] that, when exacerbated by economic, social and political factors, can contribute to suicidal thoughts and behavior.”

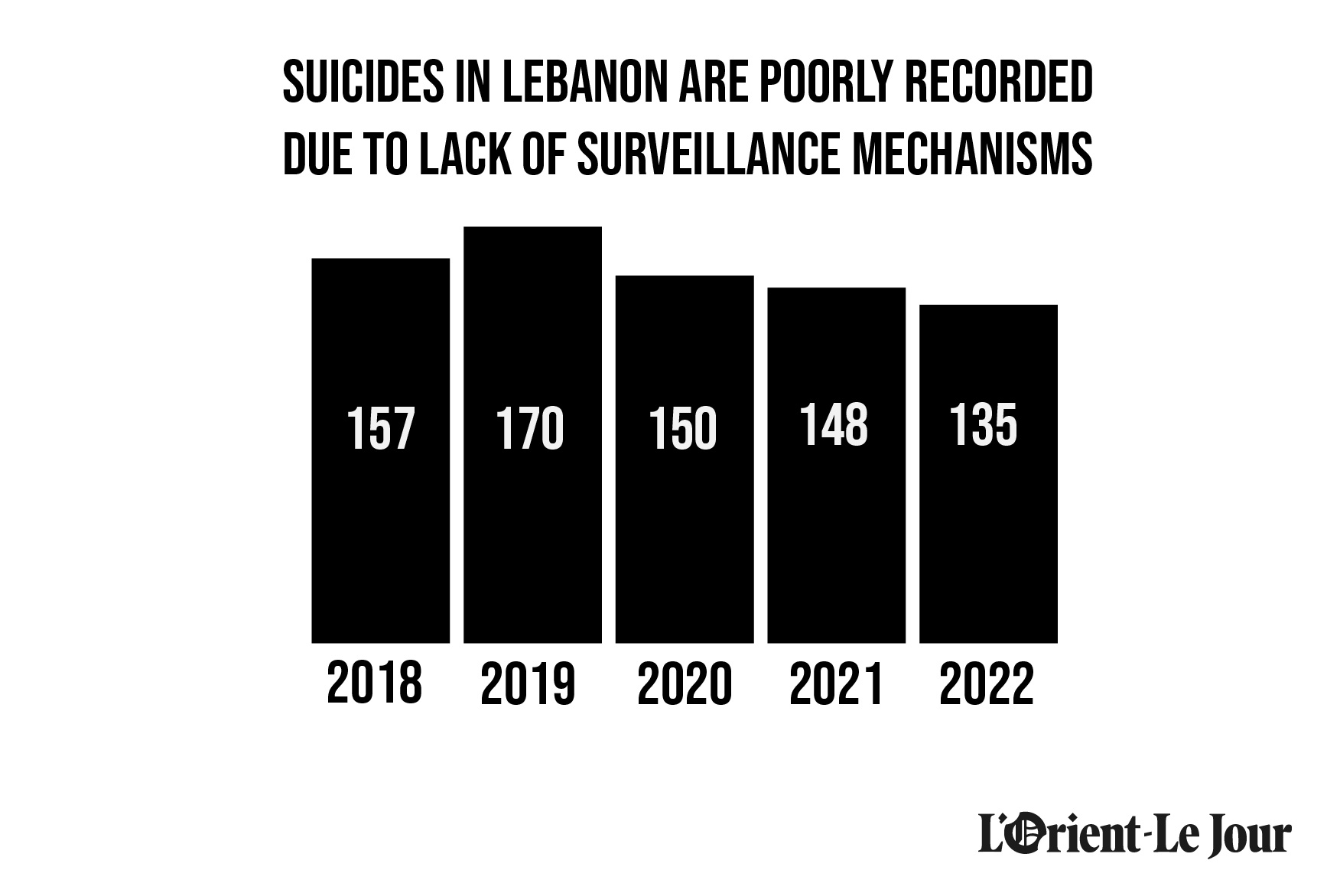

Atoui said that the recent suicide cases “are not a new phenomenon,” and recalled the wave of suicides that occurred in 2019, when over 170 people ended their lives.

“When cases of suicide are highlighted in the media, there is fear of a suicide contagion in people with predisposing factors and who are experiencing similar situations,” she added.

Moukheiber agreed. “Suicide does not mean that one does not like life, but rather that they want the pain to stop… People can say that at least this suicide victim is relieved and that they want to be relieved too.”

Credible figures?

The numbers do not show an increase in suicide cases between 2018 and 2022: 157 cases were reported in 2018, 150 in 2020, 145 in 2021 and 138 in 2022. However, it remains that this data should be taken with a grain of salt.

“These are not precise figures because we do not have a complete surveillance system,” said Rabih El-Chammay, director of the National Mental Health Program (NMHP). If Moukheiber is sure of anything, it's that this data certainly does not “underestimate” the numbers.

One reason behind the lack of clarity is the taboo that surrounds suicide. When Moukheiber was a Red Cross EMT, he had to deal with families who claimed that the death of a loved one was due, for example, to a fall in the bathroom, when clearly, “ the person had hung himself or shot himself.”

Hussein Chahrour, a medical doctor, also experienced this. “Some families do not accept this reality and want to hide it for religious, social or dignity-related reasons. Chahrour recalled a case where the family of a suicide victim accused a young man of murder. As a result of the erroneous report, the accused but innocent man was sentenced to death, only to be released 5 years later, when forensic tests proved that it was a suicide case.

A phenomenon that affects men

The victims of this recent wave of suicides were all men in their 30s and 40s. Three of them were fathers, one of them married without children. In a society where poverty and mental health are a source of shame, men do not typically speak out, or speak very little when they do.

“My biggest pain is that M.S. could have talked to me, we would have done everything we could to help him,” said Kalot.

A study titled Impact of 2008 Global Economic Crisis on Suicide: Time Trend Study in 54 countries, published in 2013 in the British Medical Journal, revealed that the rate of suicides was higher among men than women during the Russian economic crisis in the 1990s and the Asian economic crisis in 1997. One of the main reasons is the social weight placed on men. When faced with unemployment, men feel more ashamed and are less likely to ask for help, the study said.

“Men [die by suicide] three times more than women, even though women attempt suicide two times more than men,” said Atoui, adding that men are more likely to use more aggressive means, such as weapons.

Lack of hope

What increases the despair in Lebanon today is that there is no sign of a solution to the crisis. The 2008 study on the impact of the global economic crisis on suicide found that there are considerable variations in the effects a crisis has on suicide risk across countries. Such variations relate to the severity of the recession at hand, as well as to varying levels of social support and labor market protection schemes in different countries.

“The first thing to do is to solve the crisis and to ensure mental health services,” said Chammay, who recalled that the causes of suicide are multifaceted.

“People don’t know that therapy treats depression or anxiety... they tell themselves ‘I need to eat, what can a psychologist do?’…” said Moukheiber.

Many people are unaware that helpful and free resources exist in Lebanon.

Some NGOs offer free services, including Embrace, which has set up a suicide hotline (1564) in coordination with the NMHP. The NMHP also launched the Step by Step App six years ago to help battle depression and anxiety in the country.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury.