Wearing protective glasses and noise-canceling headphones, Hala cuts a piece of wood in Warsh(ee's) workshop. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

BEIRUT — Every morning at 6:30 a.m., Nasab, Mariam, Nada and Hala get on a bus in Tripoli in northern Lebanon. They make the 80-kilometer trip to attend carpentry classes in Sin el-Fil, just outside Beirut.

After struggling to find jobs in the fields they had hoped for, one year ago these four young women in their 20s decided to try their luck in carpentry — a profession traditionally reserved for men.

They receive their training at Warsh(ée) (meaning “workshop”), an initiative launched by Lebanese architect Anastasia el-Rouss after the Aug. 4, 2020 Beirut port blast.

"We accompany them in a profession that they would never have considered by themselves,” explains Rouss. “We pay them during the training to help them survive and to show their families that this is a job that can allow them to live.”

According to the World Bank, female labor force participation in Lebanon stood at 21 percent in 2021. This compares to a global rate of just over 50 percent for women and 80 percent for men.

Fighting society’s expectations, with some adjustments

“We were laughed at a lot when we started our apprenticeship, but we got over that phase,” says Hala, who dreamed of a career in the Internal Security Forces (ISF) before joining Warsh(ée). “People used to ask me how I was able to carry wood. It’s not that heavy, and if there’s a big piece we all carry it together,” she says.

Nada, an accounting graduate, was unemployed before starting her carpentry training.

“People around me made fun of me at first,” she says. “But when they saw the results of my work, they began to appreciate my carpentry.”

Warsh(ee's) workshop in Sin al-Fil. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Warsh(ee's) workshop in Sin al-Fil. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

At Warsh(ée), the workshop was adapted to suit the small stature of some of the female apprentices.

The teaching is done by men, as carpentry has long been a male-dominated profession in Lebanon, but the trainers are unwavering in their support for the young women they train.

“Our teachers, who are men, have encouraged us women to take up carpentry. It’s a real profession and we can make a living from it,” says Nasab, a graduate in social sciences who has been unemployed for months.

Asmahan Zein, president of the Lebanese League for Women in Business (LLWB), told L’Orient Today that “for women to be able to thrive they need men to walk the road with them, we can’t promote the value of women in the workplace if men don’t value and support women.”

Financial and personal empowerment

Learning the trade has empowered these young women, allowing them to start earning money and gain confidence.

Mariam, a school dropout, is proud to have “become financially independent” since she started the training.

Mariam, busy putting together the different parts of a table. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Mariam, busy putting together the different parts of a table. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

For Nasab, learning the trade has boosted her confidence and allowed her to take charge of herself.

“Before, I was unemployed and had nothing,” she says. “Today, I can do what I want. My dream was to get out of my environment and to know other ways of being and doing. In my environment, the man is always privileged; here, we are all equal.”

From left to right, Hala, Nada and Nasab proudly show off some of their creations. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

From left to right, Hala, Nada and Nasab proudly show off some of their creations. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Hard work and some affirmative action pays off

Unexpectedly, some women had it easier.

As Zein explains to L’Orient Today, “socioeconomic background affects whether the women will be welcome in a male-dominated area.”

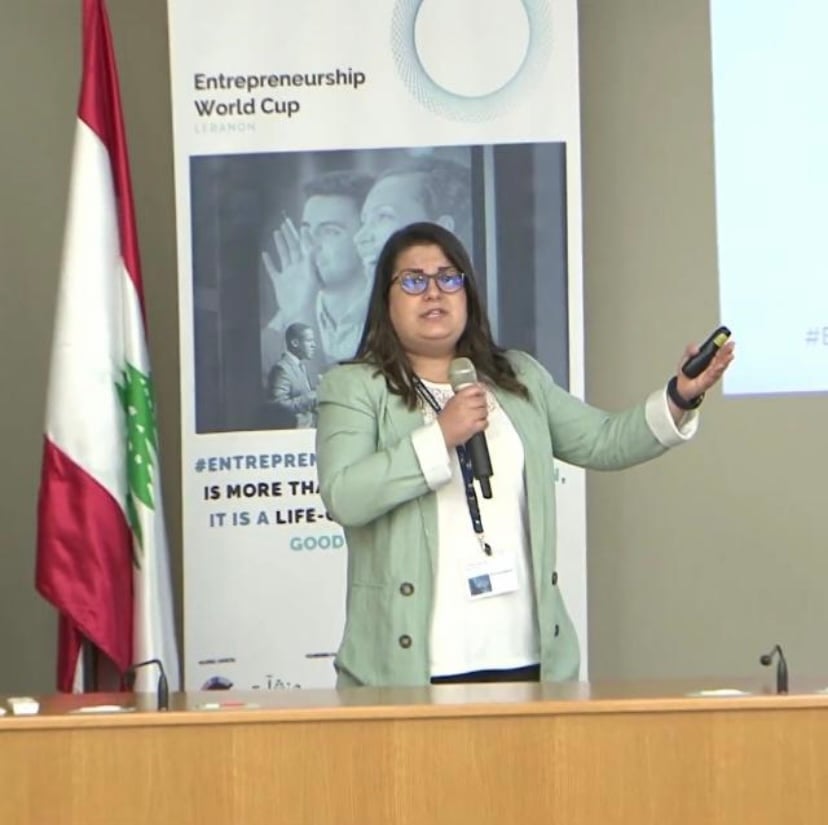

Rosabelle Chedid is co-founder and chief operations officer of “C Green,” a patented startup that turns sludge (a mud mix) into organic fertilizer.

Chedid says that “doors have opened for women in all programs,” and attributed this in part to the UN’s sustainable development goal calling for gender equality.

Rosabelle Chedid is co-founder and chief operations officer of “C Green.” (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Rosabelle Chedid is co-founder and chief operations officer of “C Green.” (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Chedid won the Femme Francophone Entrepreneur (FFE) 2019 competition for her startup. FFE is a competition specifically designed to encourage women entrepreneurs.

“I don’t believe in chance, I believe in hard work, and in the help we get from people we meet along the way,” Chedid says, noting that she has never personally faced any kind of discrimination or sexism for being a woman working in science.

Malak Jomaa, a web developer, tells L’Orient Today a similar story.

Jomaa was a student at SE Factory, an organization in Beirut that trains aspiring programmers and coders.

“I believe that I had more advantages for being a girl,” she says with a laugh. “My classmates and instructors were all really supportive and I had an instructor call me ‘a rare gem’ because there aren’t as many women in this field as there are men and they would like to see more.”

Jomaa works at a Norwegian company, in a team composed equally of male and female developers. “I think being a female gave me an advantage to get hired. My technical skills were a plus but they were also looking for girls.”

FFE winner Chedid says that “young girls in Lebanon have to follow what they want.”

“If you’re passionate about your work you will find a solution for every challenge,” she encourages.

But Zein adds an important nuance: “Any woman working in any business isn’t appreciated until she proves herself to be overqualified for the job. You have to work twice as hard [as men].”